Having learned my lesson by sitting out the first Joker’s Asylum series of ridiculously-titled one-shots in 2008, only to discover via a library-borrowed trade that the comics it produced were actually pretty damn good Batman comics, I decided that I’d be purchasing the collection of the second Joker’s Asylum series of one-shots as soon as it was published.

Having learned my lesson by sitting out the first Joker’s Asylum series of ridiculously-titled one-shots in 2008, only to discover via a library-borrowed trade that the comics it produced were actually pretty damn good Batman comics, I decided that I’d be purchasing the collection of the second Joker’s Asylum series of one-shots as soon as it was published. It proved rather difficult to do so, leaving some of these issues on the shelves and counting down the weeks until the trade was available, in large part because one of the comics in the series was drawn by Kelley Jones and, I probably don’t need to remind you, it is the opinion of this blog that Kelley Jones rules.

The original Joker’s Asylum event used up most of the A-List Batman villains (or at least the A-List Batman villains who are also incarcerated in Arkham Asylum for the Criminally Insane), devoting one-shots to The Joker, Two-Face, The Scarecrow, Poison Ivy and The Penguin.

This series had to move down a bit to the B-List then—The Riddler, Mad Hatter, Killer Croc, Clayface, Harley Quinn—but despite having lower-profile protagonists, in many ways it proved to be a superior outing. Certainly its visually superior to the original.

The premise is the same: A series of stand-alone stories in which The Joker serves as a horror-host, narrating a story in which one of Batman’s insane villains serves as the protagonist, while Batman himself generally gets little more than a cameo near the conclusion.

The first story is that of the Mad Hatter, written by Landry Quinn Walker (whose name is most familiar for his generally excellent work on DC’s kid-friendly books) and penciled by Keith Giffen, with Bill Sienkiewicz inking.

Sienkiewicz is a powerful artist, and when he inks or finishes another artist’s work, it can have a pretty dramatic effect on the style, making the lines scratchier, jitterier, shakier—Sienkiewicz’s lines are full of energy, and that energy tends to be a nervous, even nauseous energy.

Obviously, that’s a pretty good match for a story narrated by two different lunatics and mostly told through The Mad Hatter’s point-of-view, and his work fuses somewhat surprisingly well with Giffen’s.

Walker’s Hatter is less-obsessed with hats and hung-up on Lewis Carroll’s Alice books in a very specific way: When we find him, he’s writing a book, “The Mad Tea Party by Jervis Tetch,” a sort of idealized children’s romance, but he still needs to find his Alice to complete it.

He’s also doing his best to resist drinking tea or wearing hats, things he must remind himself not to do constantly, by repeating instructions not to do so like a mantra, and putting little sticky notes reading “Do Not Drink” on boxes of tea around his cluttered, hoarder’s hide-out.

Eventually he succumbs of course, and transforms from a nervous, deeply troubled crazy person to an over-the-top, Batman-battling villain.

The visuals are further enhanced by the artists drawing the panels of the comic as if they were illustrated by Tetch himself, for his book, so that pieces of some panels look like pictures torn from magazines and taped over the art Giffen and Sienkiewicz would have provided if they weren’t using this technique.

Here's one panel, featuring Batman's appearance:

It make for extremely immersive art, in which the world between The Mad Hatter’s book and the real world (which is, of course, actually the book we’re reading) overlaps—apropos for a madman who fancies himself The Mad Hatter from Carroll’s occasionally metatextual text.

It make for extremely immersive art, in which the world between The Mad Hatter’s book and the real world (which is, of course, actually the book we’re reading) overlaps—apropos for a madman who fancies himself The Mad Hatter from Carroll’s occasionally metatextual text. Harley Quinn’s story, written by James Patrick, manages to recall some of the fun of the lead character’s own short-lived series, cramming it into a single issue. It’s entitled “The Most Important Day of The Year,” and features the Joker-obsessed villainess breaking out of Arkham on Valentine’s Day to spend it with the love of her life, and refusing to let anyone or anything—incarceration, the mobs of Gotham City, the Gotham City Police Department, Batman—stand in her way.

It’s a bit of a lark of a story, well constructed from beginning to twist ending, and artist Jason Quinones provides perfect art for it—representational-esque, but with a cartoony accent, full of life, movement and expression.

That’s followed by “The House The Cards Built,” featuring The Riddler. Not unlike the Two-Face story that closed out the first volume, this one tries to incorporate the villain’s schtick into the story itself, although with less successful results.

The story, written by Peter Calloway and drawn by Andres Guinaldo and Raul Fernandez, is of The Riddler falling in love with a young woman, and then trying to solve the riddle of getting her to love him, despite the fact that he’s not only older and, I assume, unappealing, but also and more obviously he’s a psychotic criminal.

Another Bat-villain plays a role in the story, trying to initiate The Riddler into a team-up, only to find he’s too lovesick to participate, and thus the mystery villain decides to solve The Riddler’s problem somewhat violently.

To keep the identity of the villain a secret—it’s apparently a riddle—Guinaldo and Fernandez draw a different villain in the place of The Mystery Villain in every panel he or she appears in. It’s a neat trick that at least lets us see a single art-team draw the majority of Batman’s rouge’s gallery.

It’s pretty great art throughout—it lacks the style of the opening and closing chapters, and doesn’t seem quite as perfectly matched to the particular character in the way that the Hatter, Harley and Clayface stories are, but it may be the all-around best art.

The strange thing is, Guinaldo and Fernandez draw the Dick Grayson Batman costume throughout the story (it has different gauntlets and a different belt buckle, if all Batman costumes look the same to you), despite the fact that the story takes place quite a long time ago, back when The Riddler was still a villain instead of a reformed private detective, as he has been in the comics since around 2006 or so; Dick Grayson didn’t become Batman until 2009.

Mike Raicht’s Killer Croc story, “Beauty and The Beast,” is probably the messiest of the stories visually, illustrated by David Yardin and Cliff Richards, with Jose Villarrubia handling the colors. It’s also somewhat strange in how little Croc actually has to do with the story. After he breaks out of Arkham in a most unusual way—and apparently demonstrates a new reptilian power—he’s taken in by a low-level criminal and the hood’s wife.

With a silent, brooding, obedient Croc as muscle, the low-level hood climbs to the top of the crime heap, until it all plays out how any tragedy would.

It’s a pretty okay crime story, but it offers little insight into the main character beyond his being a big, animalistic reptile-man who kills and sometimes eats people.

Although, come to think of it, that’s pretty much how the character’s been used since about “Hush” or so.

For reasons that remain a complete mystery to me, the artists seem to have split up the book, with Yardin handling the early portion and Richards the later person; they have very different style, with Yardin doing very detailed work with heavier, darker lines, while Richards uses a weird soft-focus, faux-photographic style that makes his portion look like a bit like an old commercial for a feminine hygiene product—albeit one featuring a crocodile monster.

The final story was probably my favorite, but I’m biased—it’s the one drawn by Kelley Jones, drawing Clayface again (Jones last drew Clayface during his 12-issue 2008 collaboration with Steve Niles on Batman: Gotham After Midnight, and way back in 1998 Jones shared art duties with J.H. Williams III on a Clayface story during his run on Batman with Doug Moench and John Beatty).

The final story was probably my favorite, but I’m biased—it’s the one drawn by Kelley Jones, drawing Clayface again (Jones last drew Clayface during his 12-issue 2008 collaboration with Steve Niles on Batman: Gotham After Midnight, and way back in 1998 Jones shared art duties with J.H. Williams III on a Clayface story during his run on Batman with Doug Moench and John Beatty).It’s written by Kevin Shinick, and features the first Clayface, Basil Karlo, who I believe is now the only Clayface, having absorbed the others (That’s right, right? It would explain why he has the appearance and shape-shifting powers of Clayface II, and the melty-powers of whichever roman numeral-ed Clayface had the melty hands and was in love with a mannequin).

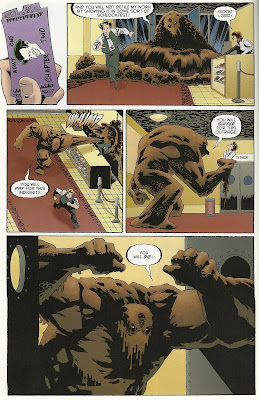

It’s often hard to separate the story from the art in a Jones story, given how showy and exaggerated that art is, but this one’s pretty solid—Clayface finds a theater showing one of his old horror movies, where kids dress-up as his character in some sort of V For Vendetta/Rocky Horror Picture Show-like celebration. His first impulse is to kill the kids, but then embraces their affection for him, and ultimately Batman’s investigates the murders around the theater only to find the villain.

Shinick offers some neat applications of Clayface’s powers, and all of the familiar Jones touches are there—weird angles, shocking close-up on ghastly expressions or incredibly detailed horror images, illustrated chapter breaks, characters’ faces appearing in the clouds of the sky, panel-background’s reacting to the emotions displayed in the actions of the foreground, etc.

There are some especially nice depictions of Clayface in action, which are refreshingly fluid. When he first storms the theater, for example, he flows in like a slow moving wave, and when he attacks a person, he splashes his arm against them like a viscous geyser.

As with the first volume, this one proves to be a nice primer to various Bat-villains, and boasts enough fresh takes and quality work to offer something for long-time fans that have no use for a primer. I also particularly enjoyed seeing multiple different takes on different characters, something I never really tire of—this volume, for example, features five Jokers and five Batman, and each art team has a different, personal interpretation of each.

As with the first volume, this one proves to be a nice primer to various Bat-villains, and boasts enough fresh takes and quality work to offer something for long-time fans that have no use for a primer. I also particularly enjoyed seeing multiple different takes on different characters, something I never really tire of—this volume, for example, features five Jokers and five Batman, and each art team has a different, personal interpretation of each.

2 comments:

"apropos for a madman who fancies himself The Mad Hatter..."

I don't think that's the correct use of 'apropos'.

I'm not sure if Basil Karlo has killed the others or not, but he did steal the powers of Clayface III (the melty hand one) and Clayface IV (a.k.a. Lady Clayface) back in the Mud Pack story back in 89/90 by the perfect Bat-team of Alan Grant and Norm Breyfogle.

Which brings to mind the question, why the hell hasn't that story been collected?

Post a Comment