I just read Brian Azzarello, Lee Bermejo, Mick Gray and Patricia Mulvihill’s Joker this weekend. You’ll likely recall it’s the November 2008 original graphic novel (of the sort that Marvel’s EIC Joe Quesada recently said doesn’t make sense for his company, but which seems to work well for DC for some reason), the one that shares a general character design and Batman-comics-as-“realistic”-crime-drama mission statement with the previous summer’s film The Dark Knight.

I just read Brian Azzarello, Lee Bermejo, Mick Gray and Patricia Mulvihill’s Joker this weekend. You’ll likely recall it’s the November 2008 original graphic novel (of the sort that Marvel’s EIC Joe Quesada recently said doesn’t make sense for his company, but which seems to work well for DC for some reason), the one that shares a general character design and Batman-comics-as-“realistic”-crime-drama mission statement with the previous summer’s film The Dark Knight. It’s the one with the gross cover, and the cool Crazy Person font logo and credits.

This book was sort of a big deal last fall, or at least DC really treated it as a big deal—despite a deep catalog of solid Joker comics to draw from, they apparently commissioned this as a signature companion to the movie (in aesthetic and worldview only) and gave it a massive PR push, maybe the biggest PR push of any DC book since I’ve been paying attention, based on the number of reviews both in the comics blogosphere and in the mainstream media (It’s quite possible, of course, that the push on DC’s side wasn’t necessarily bigger than some previous books, but instead that more venues were more eager to bite, given the book-like nature of the release and the unique heat signature of The Joker at that period in time, when the movie was huge, the promising young actor who played him had passed away, and Oscar talk was earnest).

I didn’t read it last fall precisely because of the attention it was garnering; there were no shortage of reviews of it, and given the review-whatever-I-feel-like nature of my comics criticism, I didn’t feel pressed to add another. I also made the mistake of reading Jog’s review before the book’s release, and his review was so well written I couldn’t imagine trying to “compete” with it, even if I had the exact opposite reaction he did to every element of the book (Re-reading Jog’s piece now, after having read Joker, I see it that in addition to being well written, his review was also pretty damn incisive—his description of a lot of aspects are pretty much perfect).

So if you’re wondering why I’m bothering to write about Joker almost a year after it’s release, well, now you know.

Jog did seem to enjoy the work a lot more than I did, though.

Azzarello certainly put the short-ish story together with a great deal of precise craft. In length, scope and focus, this is certainly a work that earns the “novel” part of the term “graphic novel” (although maybe “novella” is more fitting? It’s only 128 pages). But because I was reading the book for pleasure instead of specifically to review it, my mind kept wandering away from concerns of the quality and back towards more behind-the-scenes ones. For example, why did this book exist, exactly? Why did DC publish it? Why did they publish it like this, instead of some other way?

Unless for some reason this is the very first post on my blog you’re reading, then you know I’m a regular comics reader, of the sort one might call a fan, or, derisively, part of “the Wednesday crowd.” I go to the shop every week, I buy somewhere between a handful and a small stack of super-comics in their stapled, 22-page format, I pay attention and keep at least casual track of the “universe” aspects of super-comics.

As such a reader, I wasn’t sure what to make of this book at first. Was it supposed to be “in continuity;” was it supposed to “count?” Was this Joker and this Gotham City supposed to be the same one most of the other thousands of Batman comics deal with, or is it an all-new one, Azzarello and Bermejo’s own, highly personalized remix of the familiar elements? Is it supposed to be all-ages, or adult?

It’s published by DC on their DC Comics imprint, instead of their Vertigo imprint; it doesn’t say “For Mature Readers” on it, as DC comics used to once upon a time, back when they published a variety of comics for a variety of different age groups, instead of choosing to focus almost exclusively on teenage boys who might conceivably get in trouble with their parents if there were F-words or nipples in their comics, but who nevertheless want to read about guys who swear and go to strip clubs and also really, really like reading about acts of violence, the more lurid the better.

Having read through it twice now, I understand this is a standalone work. It’s supposed to remind you of the movie (or at least what Azzarello, Bermejo and DC assumed the movie would be like, based on Batman Begins), but it’s a different milieu than the movie. It’s okay if it reminds you of the comics, particularly if it makes you want to read more Batman comics, but it’s not connected; it’s not in-continuity.

For us Wednesday Crowd-ers who’ve been reading DC for at least a decade, it’s an “Elseworlds” comic without the “Elseworlds” stamp. In more inclusive terminology, it’s Azzarello’s and Bermejo’s Joker story if they were allowed to reimagine the Joker how they saw fit; this is their The Dark Knight, only it’s a graphic novel instead of a film.

Looked at like that, it’s not a bad work. It’s engaging, and has new ideas to offer in terms of personalized riffs on characters and concepts that hundreds of different writers and artists have offered their riffs on already. The route it takes to its conclusion seems new, but it goes nowhere—or at least nowhere we haven’t been before.

Joker has nothing to say that The Killing Joke didn’t say about 25 years ago—The Joker and Batman are characters (in a comic book or TV show or cartoon or movie or video game), and they fight, because one’s the villain and one’s the hero, and that’s what characters do. The Joker wins for a while, and then he loses by the climax.

Azzarello chooses different words to say this than Alan Moore (and everyone else since) did, but that’s all he really has to say about the matter. What makes this at all different is the point-of-view, and the amount of time Azzarello puts off bringing Batman into the comic at all. The ending is the ending it has to be, or at least the one Azzarello acknowledges that it has to be, but some equivocal foreshadowing aside, he keeps the proceeding as Batman-free as possible.

I imagine it analogous to a kid trying to stay up as late as possible. His parents keep telling him it’s time for bed, and he knows he’s eventually gotta, but he keeps pleading “Just five more minutes,” and they give him five more minutes.

And that’s about where I start questioning aspects of the work’s very existence. If you can turn these children’s characters into hard-boiled, pulp crime characters, if you can have these action figures drinking, popping pills, and snorting lines of representationally drawn cocaine, if these cartoon characters can butcher and skin human beings, can watch strippers and rape women, why can’t the story deviate into new territory? The acknowledgement that neither the Joker nor the Batman can ever win, that their conflicts are inevitably a never-ending series of repeating sequences is a tired cliché at this point.

And hell, if you can’t tell a new story, for the love of God, can you at least show a naked lady? An upraised middle finger? The word “fuck” spelled f-u-c-k with no cute little black bars or caps lock-ed number keys? Because this comic, like so many today, walks right up to the line of what they can and can’t get away with, farther than they need to if they’re not going to cross it, as if to point out that this is the work of a big, corporation which can’t risk offending anyone.

Wouldn’t it be bad-ass if we did this?, Joker asks. You bet it would, but we might get in trouble, so let’s not, it then answers.

And then skins a dude and lets us know that the woman over there was totally just gang-raped between pages, because that’s A-OK, as long as the penetration—serrated knife through naked man’s flesh or the Joker’s penis through the victimized woman—happens off-panel.

Shit, I sure am going on a long time here. And all I really wanted to do was highlight some weird panels that threw me out of the book and had me scratching my head and experiencing sympathetic existential angst for Joker, because it’s just a bunch of words and pictures on paper and can’t experiences it’s own existential angst.

For example, there’s this picture, of the Joker stalking out of Arkham Asylum, like the scene in a movie where the character gets out of jail after years (a scene we see later in flashback, starring our point-of-view character Johnny Frost):

That is a nice drawing of the buildings in the background, and the whole image has impact (It’s a full-page splash, and Azzarello and Bermejo actually know how to use splash pages, unlike most of their peers making DC comic books rather than DC original graphic novels).

That is a nice drawing of the buildings in the background, and the whole image has impact (It’s a full-page splash, and Azzarello and Bermejo actually know how to use splash pages, unlike most of their peers making DC comic books rather than DC original graphic novels). But all I could think of was the fact that the Joker was wearing a lady’s coat. I wouldn’t have even noticed, if Eddie Campbell didn’t notice last year, and write a very funny post about it:

It can happen because the artist is looking in a mirror, but the overwhelming reason in the last twenty years is that comic book artists generally speaking, though there are a few fashion plates to give exception to the rule, are the worst dressed people in the world who mostly get around in t-shirts and draw people in leotards.

On the very next page, I realized that this was going to actually be one of those juvenile comics. Not one for juveniles necessarily, but one of those that has the juvenile tendency to think things like middle fingers are provocative, but will only lift them when their parents and teachers aren’t looking, because they don’t want to get in trouble:

(I included part of the panel above the Joker saluting the city, so you can see the gutter and note how Bermejo drew an image of Joker flicking off Gotham City. And yes, the lightning bolt-as-middle-finger suggestion is pretty awesome, if it's intentional, although it's not something you would see reading the first time, as your eyes would be headed in the opposite direction, and probably stop at, "What the fuck? Why can't they draw a middle finger? Fucking pussies!").

(I included part of the panel above the Joker saluting the city, so you can see the gutter and note how Bermejo drew an image of Joker flicking off Gotham City. And yes, the lightning bolt-as-middle-finger suggestion is pretty awesome, if it's intentional, although it's not something you would see reading the first time, as your eyes would be headed in the opposite direction, and probably stop at, "What the fuck? Why can't they draw a middle finger? Fucking pussies!").I’m not entirely sure why, but this line of dialogue seemed incredibly wrong to me. It was at this point during the reading experience where it started to become clear to me that this book was, as Jog put it, “continuity neutral,” and that this Joker most definitely wasn’t The Joker:

For the life of me, I just can’t hear the Joker using a double negative like that. If there’s one thing that’s consistent about the Joker in all interpretations across all media, it’s that he is an eloquent, well-spoken sort of villain, the sort who never would have said “no one” instead of “anyone” in that sentence.

For the life of me, I just can’t hear the Joker using a double negative like that. If there’s one thing that’s consistent about the Joker in all interpretations across all media, it’s that he is an eloquent, well-spoken sort of villain, the sort who never would have said “no one” instead of “anyone” in that sentence. Here’s one of Harley Quinn’s big scenes. (I think she’s only ever referred to as “Harley,” though). The Joker and Frost’s first stop after Arkham is this club, where they start drinking and partying. There’s a woman wearing only an open jacket over her breasts standing at the edge of the bar, and, at one point, she gets up on stage:

I suppose she’s supposed to be dancing, but during the four-panel sequence, she takes her jacket off, revealing her breasts to the audience (but not the reader! Because this is an all-ages comic, after all), then puts on her Harley Quinn hat and mask and, off panel, her top. She’s more changing clothes on stage than stripping.

I suppose she’s supposed to be dancing, but during the four-panel sequence, she takes her jacket off, revealing her breasts to the audience (but not the reader! Because this is an all-ages comic, after all), then puts on her Harley Quinn hat and mask and, off panel, her top. She’s more changing clothes on stage than stripping. And then she and Joker peel all the skin off that moustache man’s body, from the neck down, so you can see his red muscle (off-panel). They apparently do a very, very good job, as his skin is removed but there’s no blood or incisions in the muscle, and he’s perfectly capable of running back into the room before dying.

That guy in the vest and hat is Killer Croc, by the way. Bermejo draws him more in line with his original conception as a big guy with a tough, scaly skin condition that makes him look vaguely crocodilian, rather than the sort of hulking mutant crocodile monster man he’s become in the comics. Bermejo gives him hoop earrings, and big, baggy pants, sagged to reveal the tops of his boxers.

His role is as muscle in Joker’s criminal operation, and he’s given a sort of hip-hop look. Croc’s men are all black, and dressed in fashions which my mid-nineties MTV viewing tell me are supposed to indicate that they are gangsters. (In a previous Azzarello-written Batman comic, Croc was given a pimp look, complete with huge gold chain and leopard print silk shirt).

Harley is something between a generic movie gangster girlfriend character (stripping, doing it with the main bad guy, doing lots of drugs with the main bad guy, holding him while he cries during a private, vulnerable moment), and a Frank Miller-style Amazon whorerior, although she gets one splendid moment at the end of a meeting between Joker and Two-Face.

Two-Face looks as if he could have come straight from the comics, particularly now that his scarred half doesn’t follow any regular style guide in the DCU comics.

The Penguin looks like the Penguin, fo the most part. He’s short, round, has a pointy nose, wears a monocle, smokes his cigarette from a cigarette holder, but he’s never referred to as “The Penguin,” or “Oswald” or “Cobblepot.” Instead, Joker calls him “Abner,” which I took to be a Joke I didn’t get, although it’s somewhat odd that he continues to call him only that and nothing else.

The most radically reimagined character, however, is The Riddler. Just look at this:

Those are question mark tattoos emanating from his belly button, and although you can’t see it in this image, the back of his coat has a weird, tribal tattoo script-looking image constructed of stylized question marks. It’s all just awful but hey, that’s part of the fun of the book, I suppose….seeing how Bermejo and company reinvent the looks of the characters.

Those are question mark tattoos emanating from his belly button, and although you can’t see it in this image, the back of his coat has a weird, tribal tattoo script-looking image constructed of stylized question marks. It’s all just awful but hey, that’s part of the fun of the book, I suppose….seeing how Bermejo and company reinvent the looks of the characters. And then there’s their Batman. He too is given a very If This Were Our Movie… design, very reminiscent of the hard, black, rubber and leather looking shells that Michael Keaton and Christain Bale found themselves encased in. Like Bale’s especially, there’s no yellow oval or visible Bat-symbol on the chest, other than perhaps a black bat over a black cape over a black chest plate (or it’s just a crease in Bermejo’s figure).

Batman doesn’t show up until page 110, and only get two lines, for a grand total of four words of dialogue. His existence is acknowledged throughout, with Joker occasionally shouting up at the buildings or mentioning a “he” who’s out there, but this Batman sure seems to take a long time getting around to giving a shit about the many, many violent crimes his archenemies are committing.

This is probably an intentional choice on Azzarello’s part, as he has Joker walk away from murdering a crime boss and then asking the rooftops, “Not enough for you, huh? Need me for more of your dirty work?” It’s as if this Batman only gets involved when crime turns its attention to the civilians, and as long as its criminal on criminal, he’s not terribly rushed to fight it.

That, or this Batman just really, really sucks at his job, as he seems unable to catch up with the Joker until Two-Face finally calls Batman on a homemade Bat-signal and asks for his help.

I think maybe Batman just didn’t think to look for The Joker in an original graphic novel. He was already fighting super-crime in Batman, Detective Comics, Batman Confidential, Superman/Batman, Trinity, Justice League of America, Batman: Gotham After Midnight and Batman: The Brave and The Bold, how was he supposed to know that The Joker and so many of his other rogues were hiding out in an original graphic novel, half-disguised as more straightforward crime fiction characters than their usual, more super-villainous selves?

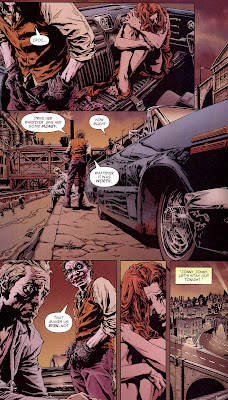

Finally, here’s a horrible page to close the post out with:

Well, the content's horrible, not the construction of the page itself. That’s The Joker buttoning up his pants after apparently raping Johnny’s ex-wife, whom Two-Face had kidnapped and tried to use as leverage.

Well, the content's horrible, not the construction of the page itself. That’s The Joker buttoning up his pants after apparently raping Johnny’s ex-wife, whom Two-Face had kidnapped and tried to use as leverage. If the new management at DC leads to only a single change in DC Comics, I hope it’s some sort of outright ban on rape in their super-comics line, or at least some sort of reduction to, like, one rape/implied rape/line of dialogue expressing a desire to rape every year.

Once again thank you very much for not making me buy shit.

ReplyDeletein my opinion = story +6; art -10. I agree with "Finally, here’s a horrible page..."

ReplyDeleteWhy should the Joker stop short of rape?

ReplyDeleteWhy should the Joker stop short of rape?

ReplyDeleteWhy should you continuously ask stupid questions you already know the answer to?

thats so fucking typical US.

ReplyDeleteif the violence has anything to do with sex, its disgusting.

other than that murders and torture porn is edgy and cool.

I started a thread on Comic Book Resources a while back on whether or not DC can continue to keep Batman in both a G and R rated world.

ReplyDeleteAs far as I know no other media tries this except the big 2 comic publishers. Disney never felt compelled to create Cinderella romance novels, Archie is happy to stay all-ages, most manga are narrowly focused on their own age group. Yeah there are some oddities like R-rated Rambo gettig a cartoon but for the most part companies keep their characters in their age-band.

I really think it would have been better for DC to make a new character, call him the Dark Knight who goes off and fights cannibal rapists while Batman remained a kid-friendly dude.

Clearly, the success of the Dark Knight movie is a strong argument that Batman may have more appeal as an adult-oriented property, so why shouldn't DC cater to that market?

ReplyDelete"Clearly, the success of the Dark Knight movie is a strong argument that Batman may have more appeal as an adult-oriented property, so why shouldn't DC cater to that market?"

ReplyDeleteBecause it's simultaniously pushing the same character is a kids cartoon (Brave and Bold) and several kid-friendly toys and comics.

So parents assume that anything with Batman, like anything with Mickey Mouse is kid-friendly.

Till they pick up something like Joker...

Based on the cover, I don't think parents are going to assume it's the same fare as the cartoons.

ReplyDeleteThat's like saying those same parents are going to take their kids to see Dark Knight because it's the same character as in the cartoons.

That's like saying those same parents are going to take their kids to see Dark Knight because it's the same character as in the cartoons.

ReplyDeleteOn the other hand, The Dark Knight had a rating to help those parents make their decisions (I still saw a bunch of little kids in the theater when I went, of course), while Joker's got nothing.

I don't think DC needs to go the route of the MPAA, but I don't see the harm of slapping that tiny little "For Mature Readers" stamp on the cover of books like this.

DC has this weird reluctance to ever admit officially that anything they publish outside the vertigo line isn't all-ages, but they publish a ton of content that is often as or more objectionable than what you'd find in a Vertigo book.

A rating would help spell it out, but just as a parent can see the Dark Knight previews and get a good sense of the content of the movie, I think Joker is one graphic novel you can very easily judge by its cover. It's a creepy enough image that, really, who would assume the interiors would be anything milder?

ReplyDelete