Wait a minute, is this cautionary tale of a couple of young, hard-working kids who created one of the most recognizable and profitable original characters of the 20th century, inventing a genre that would eventually buttress the emerging American comic book industry for much of the second half of that century in the process, only to get infamously screwed over in one of industry’s earliest and most blatant act of creators getting screwed over even appropriate for kids?

Wait a minute, is this cautionary tale of a couple of young, hard-working kids who created one of the most recognizable and profitable original characters of the 20th century, inventing a genre that would eventually buttress the emerging American comic book industry for much of the second half of that century in the process, only to get infamously screwed over in one of industry’s earliest and most blatant act of creators getting screwed over even appropriate for kids? That was one of my thoughts when I first heard of writer Marc Tyler Nobleman and Ross MacDonald’s 2008 picture book Jerry Siegel, Joe Shuster and the creation of Superman. Theirs is not exactly a happy story, and although there are some happy endings in it—when their Superman first became a hit, when they became superhero comic superstars, when they managed to shame DC into giving them creator’s credits and some financial reward in the late seventies—it’s mostly a dark and, I’d say, tragic one. This being real life, there aren’t really any “endings,” happy or otherwise, so the above-mentioned victories were all temporary ones, followed by later trials and tribulations.

Even today, when the two boys of steel-turned-men of steel have passed on, their families are still locked in legal battle with the corporation that owns their creation (or “owns,” I guess, since ownership is one of the things being contested), and they and their memories are regularly subjected to ignorant smearing from anonymous fans of the genre they created and even very smart people working in their industry who should really know better.

Another was a rather intense curiosity about how one would go about writing a children’s picture book on the subject that wouldn’t necessarily be sanctioned by DC Comics, as the highly visual nature of picture books would seemingly require a lot of images of Superman, which DC could certainly object to the usage of (A point that was raised by the cover itself, which does have the word “Superman” on it, but the hero is pictured only as a vague strong man silhouette; if you already know Superman, you can see how that image is a blacked out one of him, but if you don’t…?

Nobleman solves the conundrum of telling Siegel and Shuster’s story without making it a tragedy by very carefully choosing where to begin and end his tale.

He focuses on the boys, particularly Siegel, at the beginning, and the difficulties of their early lives, with the decision of one editor from a company (that’s exactly as specific as Nobleman gets with National’s purchase of Superman from the boys) decides to buy their strip for “a new type of magazine called a comic book” being the climax, and the late Great Depression era’s embrace of the hero being the happy ending:

He debuted in 1938. His comic book was an instant hit. Soon he also won fans in a comic strip, on the radio, in animated shorts, in books, and in movie serials. When television caught on, he got a show there, too.The last two pages sum up the visionary qualities of the Siegel and Shuster, and then skips past all of the unpleasant aspects of their relationship with National and comics in general between the late ‘40s and late ‘70s, ending with the words, “And today, on every story where his name appears, theirs do, too.”

It’s a smart strategy, one that accentuates the positive and simply avoids the negative. The story portion of the book doesn’t alter unpleasant facts; it just tactfully ignores them.

And then, right after the illustrated story portion of the book, Nobleman offers a three-page prose article entitled “The Greatest Superhero of All Time,” which offers up a nice, thorough summary of the real warts-and-all story.

“Superman went on to rescue just about everybody from just about anything,” it begins. “No cat stuck in a tree was insignificant, no menace threating the universe was insurmountable. Two people he couldn’t save in the nick of time, however, were his creators.

The next three paragraphs sum up what the story portion of the book covers, but it goes on for pages and pages, naming DC Comics, naming the $130 price they paid for Superman, the fact that first print run of Action was 200,000 (Hear that, Justice League #1?), the Look strip in which Superman captures Hitler, the Jewishness of Superman and his creators, their gradual alienation from their character and DC, and their 1975 press offensive inspired by the fact that Marlon Brando was to earn $3.7 million for twelve days of shooting his supporting role in Superman: The Movie, which Superman’s fathers were getting exactly nothing from the movie.

It continues their stories to the end of their lives, and to the current day, noting that legal negotiations continue, and, ending on an upbeat, noting that in 1936 the pair created such boastful taglines for Superman as “the greatest superhero of all time.”

“They were charmingly bold boasts that came true,” Nobleman concludes, “and still are true more than seventy years later.”

Back to the story itself, Nobleman reverse engineers a biography of the two from the power fantasy of their Superman stories (which, the argument can easily be made, was a power fantasy engineered from the inspiration of their real lives).

Siegel didn’t like school and the people there, not as much as he liked heroes like Tarzan and Buck Rogers and the pulp magazine that published their stories. He read them, and wrote his own stories, instead of plying with the other kids or talking to the girls he liked.

The kids he knew weren’t interested in the sorts of things Jerry was, “except Joe Shuster.”

Nobleman presents Shuster as anagalous to Siegel, only he did with pictures what Siegel did with words. Together they planned to come up with their own Tarzan-like character, sell a comic strip to a newspaper syndicate, and write and draw the sorts of stories they loved for a living.

Nobleman tells a semi-mythological sounding story of a night where Siegel tossed and turned, frantically wishing he had something special going for him, elements of Superman’s story coming to him one at a time, and staying up all night, he feverishly writes them all down, runs to Shuster’s house the next day, and, his friend similarly possessed, he watches as Shuster spends the day feverishly drawing.

This is the story Nobleman’s telling, a Horatio Alger-like story of two kids with big dreams, a lot of talent and a lot more hard work inventing something that could help them achieve those dreams and, a few story beats later, selling it and being embraced for their creation.

I wonder how MacDonald’s artwork would look to eyes other than mine (or the eyes of someone unfamiliar with Shuster's Superman art), as I was quite struck by how much his Siegel and Shuster look like Clark Kent, how much they look like one another, and how hard to read they are (we never see their eyes through their opaque glasses, save a few images where they, somewhat ironically, have Captain Marvel-like curved slits for eyes).

Of course, MacDonald is quite deliberately drawing in a style evocative of Shuster’s, a pretty inspired choice that gives the book a resonance it would otherwise lack, and a way of visually communicating how much the boys drew form their own lives in creating their masterwork (something the text drives home) and a way of portraying Superman that gives the book something of a documentary feel, and, I think, excuses any question over whether or not they were stepping on DC’s legal toes (Like, MacDonald wasn’t drawing Superman to sell a Superman book; instead he’s clearly drawing Superman like Shuster drew Superman because Shuster’s his subject matter, and Superman is what Shuster drew).

While the Man of Steel doesn’t appear on the cover, he is on the title page, and on the last page, flying off into the sunset.

While the Man of Steel doesn’t appear on the cover, he is on the title page, and on the last page, flying off into the sunset. The only other appearances he makes within are in a sketch of Shuster’s, on the cover of Action Comics #1* and then seen in the distance from behind, in black and white, on a movie screen.

The only other appearances he makes within are in a sketch of Shuster’s, on the cover of Action Comics #1* and then seen in the distance from behind, in black and white, on a movie screen. I really liked the image that’s on the inside and back covers:

The heart of the story is that night and day when Siegel imagines Superman’s powers and then Shuster brings them to life.

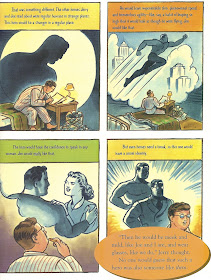

The heart of the story is that night and day when Siegel imagines Superman’s powers and then Shuster brings them to life. This occurs in a rather remarkable four-page series, beginning with a two-page spread in which young Siegel is shown imagining doing Superman-like things (leaping over a tall building in a single bound, hoisting a car over his head) and then,

on the next page, as his ides begin to crystallize, the book takes on the form of a comic book for the next two pages—the only time it deviates from the more standard text-floating-above illustrations format of a picture book to resemble comics.

on the next page, as his ides begin to crystallize, the book takes on the form of a comic book for the next two pages—the only time it deviates from the more standard text-floating-above illustrations format of a picture book to resemble comics. In these, we see a proto-Superman who lacks his S-symbol (for Siegel and Shuster, a sort of signature hidden right in their creation’s logo), his signature cape and colors, as MacDonald draws him as a sort of empty character template whose details Shuster’s imagination has yet to fill in.

In these, we see a proto-Superman who lacks his S-symbol (for Siegel and Shuster, a sort of signature hidden right in their creation’s logo), his signature cape and colors, as MacDonald draws him as a sort of empty character template whose details Shuster’s imagination has yet to fill in.It was a very welcome read, even—especially?—now, a few years after it’s release. In a time when people are still occasionally arguing about Siegel and Shuster and National and DC, about who did what and who deserves what, in a time when creators and corporations and commentators continue to wrestle with ideas of creators rights and so many of us look to Siegel and Shuster’s biography as a cautionary tale, one of the bigger, darkle black marks on an industry history that often seems to have more black marks than bright spots, it’s nice to see the positive, heroic aspects of Siegel, Shuster and their incredible creation given this much emphasis.

Whatever happened after they got their big break, Siegel and Shuster did create Superman, and through inspiration and hard work, their dreams really did come true, even if only for a while.

*Sadly, the way MacDonald draws the cover of Action #1, the National suit holding it aloft covers the lower left corner of the cover. Which means we don't get to see how he would have drawn the best element of that cover. You know, this guy:

No comments:

Post a Comment