The contents of that issue, on the other hand, are quite surprising, maybe even shocking--even more so when read today than they might have been in 1988. The issue, by the British writing team of John Wagner and Alan Grant, was a 22-page superhero adventure comic in which the Dark Knight Detective battled neither street crime nor one of the many colorful super-villains of his expansive rogue's gallery. Rather, Batman fought state-sponsored radical Islamic terrorists, who struck in both DC Comics' faux New York City Gotham City and London.

It's somewhat unsettling to read it today, and realize that it was published 13 years before the September 11 attacks...and The Dark Knight Returns cartoonist Frank Miller's expressing his desire to create a Batman vs. Al Qaeda comic called Holy Terror, Batman. And it was d 23 years before Miller's ultimately Batman-less Holy Terror saw publication.

I wouldn't make too much of the predictive nature of the comic though, given that terrorists of all nationalities, religions and ideologies have so long been a staple of Hollywood action movies and superhero comics by that point, particularly in the 1980s, but it's worth remembering how weird and unbalanced Miller's reaction to terrorism was when reading this comic about Batman fighting terrorists. After all, this was just another issue of the two Batman monthly comics of the time, and yet it was well-written, well-drawn and offered a fairly nuanced view of terrorism as both a particularly wicked, evil act and desperate flailing from doomed parties facing an invincible enemy.

Playing the part of the unstoppable super-power fueled by righteous anger and tempered by a guilty conscious is, of course, Batman.

Wagner and Grant, who as Europeans living in the United Kingdom were much closer to real acts of terrorism than their North American peers in the industry, entitled their story--sigh--"An American Batman In London." Because...Batman is American, I guess. And, you know, that movie. It opens with some mildly and typically purple narration:

Gotham:This appears in narration boxes through a title page montage of Batman doing his normal thing: Busting a drug dealer, pursuing a getaway car, catching crooks who have just robbed a jewelry store. He's in an alley near the "Gotham 'Nam Vets' Club" beating up a trio of muggers when two men in long coats walk right by and enter the club. They pull out automatic weapons and strafe the interior of the club, shouting, "For the glory of the revolution! Allah Akbar! Allah Akbar!"

Night after night, the eternal war rages. A lone cloaked figure reigns against the hosts of evil.

Time after time he gains the victory, wins the battle--only to plunge back into the war with undiminished fervor.

But there are a million crimes-- and only one Batman...

While the mention of "the revolution" might call to mind a particular country in the Middle East whose revolution was just about a decade old at the time, these men's nationality will be revealed shortly; regardless, the use of the Takbir as a battle cry unequivocally points to the shooters being radical Islamic terrorists.

Batman arrives too late to do anything but survey the damage, and on the next page he's joined by Police Commissioner James Gordon and FBI Agent Zak Hoffer. As they discuss what happened--seven dead and 13 wounded in the mass shooting, the perpetrators having committed suicide via cyanide capsule--Hoffer tells them he's 95-percent sure that the man behind the attack is Abu Hassan, "a fully accredited Syraqui diplomat," and there's nothing the U.S. government or the Batman can do to bring him to justice. A furious Batman points and screams in Hoffer's face, saying no one can commit murder in his city and get away with it by claiming diplomatic immunity.

A few things of interest here. First of all, we find out that the man behind the attack is "Syraqui," which I guess means he's from "Syraq," one of those fictional countries that occasionally appear in superhero universe comics so that the creators can use a nation state without naming a real one. Here, Grant and Wagner seem to have simply smooshed "Syria" and "Iraq" together. Similar fake countries in the region include Qurac and Khandaq.

The use of a fictional country here is in sharp contrast to the Jim Starlin-written "A Death in the Family" story arc from Detective's sister book, Batman. In the climax of that 1988 story--the final issue of which was cover-dated January 1989--The Joker was made Iran's ambassador the United Nations, and was able to fend off Batman's vengeful attack on him claiming diplomatic immunity (Actually, Batman still went after him, but Superman intervened at the United States government's behalf). Detective Comics #590 was cover-dated September 1988, so these two stories were likely being written almost at the same time, with the Wagner/Grant story seeing publication just before the Starlin one.

Learning that Abu Hassan was on his way to the Syraqui embassy in London when the attack had taken place, Batman decides that "Maybe it's time Bruce Wayne took a vacation!", stuffs his Batman costume in a duffel bag (sans utility belt) and flies to London...in a passenger plane, rather than taking a personal jet or Batplane.

It just so happens that the night he arrives is November 5th, and so the city is full of kids and firecrackers and bonfires and burning effigies celebrating/commemorating a 17th century attempt to blow up parliament. With explosives. (If you're curious about those other DC-published comics by British writers that feature Guy Fawkes Day, it looks like the first two-thirds or so of Alan Moore and David Lloyd's V For Vendetta would have been published in Warrior years prior to this issue of 'Tec being released, and the first issue of the DC-published version actually had the same cover-date as 'Tec #590. Grant and Breyfogle were fans of Moore and Lloyd's comic; their Anarky character was designed to resemble the hero from V For Vendetta.)

Batman sneaks into the Syraqui embassy, where we get more clues about the character of the nation. It's official name is "The People's Republic of Syraq." The embassy includes a flag that resembles a blend of flags of several from the Middle East, having the basic lay out of the flags of Jordan and Palestine, but with the three colors of the Iranian flag and a big yellow, five-pointed star that resembles the green ones on the Syrian flag added to it. We also see some statuettes that look vaguely Persian, a pair of crossed scimitars hanging on a wall and a poster of two fists holding a hammer and sickle, suggesting a Communist nation. "Syraq" then is basically designed to be an admixture of America's geo-political rivals and enemies in the late 1980s, although despite the vagaries of the nation, the script continually makes clear that the characters are all Muslim: "May Allah go with you, my friend," "By Allah!" and so on.

Once inside, Batman quickly beats up and ties up two armed guards and confronts Hassan, who is in the process of packing up to get on another plane. Hassan has just set another terrorist attack in motion, having planned a fifth of November that the English will remember "for the next four hundred years!"

Batman attacks as soon as Hassan pulls a gun on him, and it's a fairly one-sided fight, although Hassan puts some effort into it.

I like the bit where the Syraqui diplomat says to Batman, "I do not know who you are, American--" Really? He doesn't know who this man, dressed as a bat is...? It's not a terribly ambiguous costume. Batman's costume is so simple that it seems as if one who has never heard of him could pretty easily land on his name by chance, simply by describing him. Or, at the very least come pretty close, landing on, say "Bat Guy" or "Bat Dude" or "Mr. Bat Person."

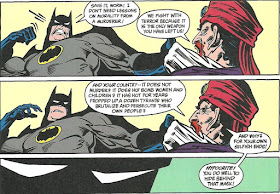

After breaking Hassan's arm and knocking him around, Batman grabs the bloodied diplomat by the collar and lifts his other fist, demanding he explain his earlier talk of a "little parting gift." Hassan makes a speech:

You Americans--and your British kin--you think if you shout loudly enough, if you bully enough, you will always get your way!Hassan's charges here are vague ones, things that were and are undoubtedly true of The West, or the First World, or the developed nations--however one might want to refer to countries like the U.S. and U.K. They are all general enough that no particular politics or policies or religion or conflicts are named. The effect here is also that regardless of how despicable Hassan and his allies' methods might be, one can't argue with the substance of the above passages. The strong do exploit the week, our plastics and technology are bad for the environment, money does corrupt.

It is time you learned the world does not dance to your tune! Have you never wondered why we hate you? Why poor and beleaguered peoples the world over count you as their enemy?

...

You exploit the weak--you rape their lands with your plastic technology--you corrupt their people with your almighty dollar! And then you dare to look so aggrieved--so innocent--when we strike back!

The dialogue is accompanied by four images of poor and starving-looking skeletal people, including a weary-looking baby covered in flies and a young black child holding an empty bowl.

Batman, who can't see the images we are being shown, isn't convinced, but Hassan starts to get to him with the next few lines.

"We fight with terror because it is the only weapon you have left us!" he says, before going on cast terrorism as a reaction to blowback for American foreign policy; Wagner and Grant are still talking in vagaries here, but they are getting more specific, as they move from the generalities of exploitation to specific categories of actions: "And your country--it does not murder? It does not bomb women and children? It has not for years propped up a dozen tyrants who brutalize and persecute their own people?"

Visually, this plays out across two pretty much perfect panels, as we see Batman's fury dissolve from his face and his fist unclench as he realizes that whatever else Hassan has done, he's not exactly lying when he says the United States doesn't always live up to its purported ideals in its foreign policy, perhaps especially in the Middle East of the 1980s (or 1950s, '60s, '70s, '90s, '00s and so on). As the angry white triangles of Batman's eyes change shape, the discussion is cut short. Hassan reveals that he has directed men to attack Parliament, and then another of his men attacks Batman form behind, slipping a garrote over his throat.

Batman is able to fight off his attacker, but in struggle, the man's flailing leg strikes Hassan, knocking him out the window, to be impaled on a spike atop the barbed-wire covered wall around the embassy. Batman, who famously spares his foes and has an almost pathological aversion to killing that can seem downright insane when applied to the many serial killers and terroristic arch-foes he regularly battles, isn't t all that broken up about seeing Hassan land on a spike with a "THUTCH". Batman merely makes a face, and narrates, "A murderer is dead--but my job isn't over..."

Quickly realizing that no one in authority is going to believe him when he says someone is going to blow up Parliament on Guy Fawkes Night, Batman steals a car and speeds there himself. Meanwhile, four men in Hassan's employ check their machine guns and fill a brief case with dynamite, and head for Parliament. They are just gunning down the guards when Batman careens into view. The Dark Knight decides he only has one play, and he steers his speeding car directly towards them, throwing himself out the door as it strikes them...

...and there is a terrific explosion.

They all die, of course--their plan was to die, as Batman narrates on the way--and they die because they are carrying a bunch of explosions, but one wonders about Batman's plan here, too. Throwing batarangs or punches at guys' heads all the time might kill some by accident in the real world, but if Batman called such methods non-lethal, he could probably convince you to accept that he can totally beat people unconscious without killing them. A speeding car though? That seems a lot harder to calibrate to a non-lethal ramming speed.

Check out that last panel. It looks rather familiar, doesn't it? Batman's wounds there are all fresh, but that image of Bruce Wayne stripping off his bat-shirt to reveal a wound-wracked back was later produced by Alex Ross in a painting for the 1996 Batman: Black and White miniseries.

On the last page, Batman tosses his costume into a nearby fire, where The Batman can burn in effigy (and evidence of his presence in London can be erased), and he doesn't seem that broken up by the five deaths he had a hand in.I'm not saying he necessarily should, but it's the sort of thing Batman tends to castigate himself over. He is, however, is haunted by Hassan's words when he basically told off Batman/The United States/The West.

Wagner, Grant and Breyfogle--and this issue--don't provide an answer. There's no Aesop-like moral here, no solution to a problem they raise. They just raise it. And they did it in a comic book that children could have bought for 75-cents off a rack in a grocery store or drug store, decades before Frank Miller wanted to use Batman to draw a revenge fantasy for the 9/11 attacks and a serious and sustained national conversation for how America should confront global terrorism systematically was begun. That seems strange in 2018, where this would have cost $4 and one would have to travel to a specialty shop to secure a paper copy. But then, so much about this comic seems strange in 2018.

*The issue has been collected in both in 2015's Legends of The Dark Knight: Norm Breyfogle Vol. 1 and the just recently-released Batman: Dark Knight Detective Vol. 2.

This was an enjoyable review of a comic I've never read. Thanks for writing it!

ReplyDeleteI have to take the time to re-read the Grant / Breyfogle run. Their run on Batman is ultimately was my gateway to DC Comics (I was a total Marvel Zombie before it).

ReplyDelete