BOUGHT:

Three Rocks: The Story of Ernie Bushmiller, The Man Who Created Nancy (Harry N. Abrams) This month's comics purchase was made in preparation for the upcoming Nancy Fest at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum in my old home of Columbus. Cartoonist Bill Griffith, best known for his Zippy the Pinhead strip, will be giving a presentation on his 2023 book, and I wanted to be ready for it by having read it.Unfortunately, my local library didn't have access to it, so I had to resort to buying my own copy, something you may have noticed I've increasingly tried avoiding doing with comics (Not simply because comics are getting more expensive and writing about comics isn't getting any more lucrative, but mostly because my comics midden, groaning bookshelves and precarious To Read piles have reached the point that they are simply too large for someone who doesn't own their own home to keep adding to).

Having now read it, I'm kind of surprised I hadn't heard about it at all in the months since its release last August (Although I suppose I don't read as much comics news as I once did...and comics news doesn't get covered as well as it used to on the Internet; The Comics Journal covered it, as did a lot of mainstream, legacy press, being covered in The New Yorker, The New York Review of Books, The Wall Street Journal and The Atlantic).

Griffith naturally uses the most appropriate medium for a biography of a cartoonist, telling Bushmiller's story as a graphic novel, with all of the liberties that allows. Much—in fact, most—of the book is in told in a straightforward, realistic style in Griffith's black and white, the thin linework and cross-hatching far removed from the bold-lined, machine-precision work that Bushmiller is famous for...although the styles intersect, and frequently.

That's because Griffith uses Nancy—and, occasionally, Sluggo and Fritzi Ritz—as a tour guide of sorts to Bushmiller's life, the familiar little girl icon breaking up chapters with regularity, using what appears to be repurposed and recontextualized work of Bushmiller's, although it's clear that Griffith can do his own impression of Bushmiller's Nancy, given how frequently the character appears on the pages and in how many different ways her image is employed throughout.

This being a visual medium, rather than a prose affair, Griffith has a great deal of freedom to show us examples of Bushmiller's work, not only by neatly plopping them onto the pages, as a prose bio could just as easily have done, but by incorporating them into the story itself. It's one thing to read that Bushmiller sold his first gag or took over the Fritzi Ritz strip, for example, while it's quite another to see the actual strips presented to us as we're being told, without it even interrupting the flow of the narrative.

Griffith, who took the title of his book from a common element seen in the background of many strips, something he considered "the boiled down essence of Bushiller's universe", opens in 1949 with a vignette about the successful Bushmiller taking a business meeting with a sponsor, all the while preoccupied with his latest strip. He had "the snapper," the gag that worked as the "catnip" for the audience in the very last panel, he just had to work backwards to figure out how to get the strip to its pre-ordained climax, a peculiarity of the way he worked (Another would be, later in his career, working at four separate drawing tables on four separate strips at a time, to keep himself from getting bogged down or bored with the work).

From there, we get a fairly straight, chronological biography of Bushmiller, from his childhood to his first newspaper job as a copy boy at The New York World, his first comic strips to taking over Fritzi Ritz, the introduction of Nancy and her gradual takeover of the strip, his time in Hollywood, his becoming a New York big shot and, eventually, becoming successful enough to move out to Connecticut, where he would spend the rest of his career and life on the strip that made him a legend.

Although there's a chronological, A-to-Z story to be told, Griffith takes plenty of fanciful detours, including imagining a Krazy Kat/Fritzi Ritz crossover comic after he meets with George Herriman, passages on the persistence of Aunt Fritzi cheesecake in the strip, space given over to Mad Magazine parodies, a section set in a stereotypical beatnik coffee shop where intellectuals discuss the strip told and drawn in the style of John Stanley, an interview with one of Bushmiller's assistants, a long-ish but welcome section in which Griffith simply shares Nancy strips for almost 20 pages and, most frequently, visits to the entirely imaginary Bushmiller Museum of Comics Art (B-MOCA) in Stamford, Connecticut, where curator "Griffy," Griffith himself, lectures the assembled crowd about the artistic merit of Nancy, the deceptively sophisticated techniques Bushmiller employed in what seems a simple enough sight gag-driven strip, and the meaning of the strip, as well as its deserved place not only in the pantheon of great comic strips, but also as fine art.

In addition to a rather complete biography of the cartoonist and the cartoon while he drew it (the first post-Bushmiller strip appears, but we're mostly left with the simple knowledge that the strip continues to this day, rather than any exploration of its post-Bushmiller existence), there's also a rather trippy sequence in which the dying Bushmiller is accompanied by his creations to a heaven of sorts where he sees on a billboard the perfect gag, and a stranger-still epilogue in which "Griffy" returns to B-MOCA to interview the now elderly Nancy (who looks just as she always has since the design stopped evolving, save for here she has white hair).

It's quite a tribute to one of our greatest cartoonists, and, importantly, it's the work that Bushmiller and Nancy deserve.

I found the imaginary museum, drawn with columns out front and hanging posters featuring Nancy and Sluggo an intriguing image, particularly given Griffith's scheduled appearance as a real-life museum of cartoon art. It's been a while since I've visited the Billy Ireland, and I of course have no idea to what extent OSU will decorate it and how, but I have to wonder if it will be like Griffith's imaginary museum made real or not.

BORROWED:

Batman/Superman: World's Finest Vol. 3: Elementary (DC Comics) The third volume of writer Mark Waid and artist Dan Mora's Silver Age-set team-up book contains two stories.

The first, guest-drawn by penciler Emanuela Lupacchino and inkers Wade Von Grawbadger and Norm Rapmund, is a done-in-one depicting the disastrous date of Robin and Supergirl, both as it unfolds and as each talks about it to their respective superhero partner, Batman and Superman. It goes so badly—Robin shows up in costume, forgets his wallet after accidentally bragging about how the ward of billionaire Bruce Wayne doesn't have to worry about the upscale prices at the fancy restaurant they've chosen—that when a bizarre car accident involving a monkey, a bus and a tractor trailer full of bowling balls occurs right outside, it comes as a relief.

It's great fun, especially the bits of conversation between sidekick and mentor that occur after the fact, and Waid does a pretty fine job of showing a date-gone-wrong without painting either character as "the bad guy" in this situation. (It basically seems to boil down to Dick Grayson not really being ready to date yet, if you ask me; that and the fact that the pair are rather ill-suited to one another, at least as Waid writes them here.)

So if you've ever wondered why Dick Grayson and (this version of) Supergirl never dated, now you have an answer.

The rest of the volume is devoted to the five-part title story, which begins as a locked-door mystery involving Metamorpho and his supporting cast—billionaire industrialist Simon Stagg turns up dead, and the two major suspects seem to be Bruce Wayne and the Element Man himself—and quickly spirals out, bigger and wider, until new villains are introduced (one of which is an evil opposite of Metamorpho, the main one of which is also an update of a classic DC character, a move reminiscent of plot points from Tom Peyer's late, great Hourman series) and the entire world seems to be under threat of a robot uprising.

To his credit, Waid actually treats his book as one set firmly in the DC Universe shared setting, albeit a past version of it, and thus many other heroes are involved in what is, of course, a threat to their entire world. And so we get lots of guest-appearances throughout the book, from cameos of the likes of Plastic Man, the Doom Patrol, Martian Manhunter, Captain Marvel, The Flash and Firestorm to more substantial roles for the likes of The Metal Men, Green Arrow and, of course, Metamorpho, whose origin is retold and is rather integral throughout the storyline.

Waid, obviously, has experience with just about all of these characters, and writes them all quite well, just as Mora draws the hell out of them. It's a treat to see so much of DC's deep, colorful bench get some time in the World's Finest spotlight, even if, for some characters, it's only a panel (Black Lightning) or two (Batgirl).

This book has been—and, here, remains—a blast, and one that I feel is made directly to appeal to a reader like me. I look forward to the next volume.

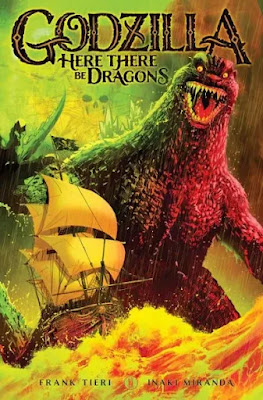

The year of 1556, and a pirate named Hull is about to be hanged for his crimes. To buy time, and perhaps bargain with the British authorities, he offers to tell the fantastic tale of what he witnessed while sailing under Sir Francis Drake, a tale of a real, live, fire-breathing dragon, a bevy of other monsters and a bizarre conspiracy of monster-worshippers that reaches all the way to Queen Elizabeth herself (the last of which is revealed in Miranda's most striking panel, of robed men wearing elaborate masks that look like the heads of Godzilla, Mothra and other familiar Toho kaiju).

The story is pretty simple, actually. There's a story of an immense horde of treasure hidden by pirates on a remote, uncharted island called "Monsters Island." After engaging the Spanish Armada and being caught in a terrible storm, Drake finds himself there, and face-to-face with the aforementioned fire-breathing dragon, whom Hull names "Godzilla." (Where did the name come from? It is later seen carved in English into the walls of the monster's Monster Island cave home.)

After making short work of the Spanish Armada, one ship of which had the audacity to fire upon him, Godzilla submerges and leaves our protagonists alone. It's interesting plugging the Toho menagerie into the roles of sea monsters in a pirate tale, but the technology of the era isn't quite up to challenging their likes. Only one man survives, a man who has sworn revenge on Drake, and helps provide some more human-scale drama to the unfolding events...a welcome conflict, seeing as how the humans are even less of a match for the monsters than they usually are in the franchise's various film cycles.

On Monster Island, Drake, Hull and the rest of the crew meet giant sea turtles and giant bats and, ultimately, a pair of name rivals who challenge Godzilla, the two members of Toho's monster roster that best fit the description of "sea monsters": Ebirah, from 1966's Ebirah, Horror of the Deep/Godzilla Vs. The Sea Monster and Oodoko, the giant octopus that attacked Kong in 1963's King Kong Vs. Godzilla.

The existence of other monsters is hinted at, not just in the panel of the masked monster-worshippers that reveals the likenesses of several of the monsters, but in one of Miranda's panels showing a map with old time-y sea monsters drawn around the edges along with the likes of King Ghidorah, Rodan and Mothra, another scene where Hull discusses monsters "throughout history" that shows the same trio plus Hedorah (how a pollution monster could exist before the Industrial Revolution, I don't know) and, finally, a brief sequence where a list of Godzilla's enemies is rattled off, and we hear the names Titanosaurus and King Caesar (along with simplified, hieroglyphic-like images of them). (Finally, Anguirus, Gigan and Megalon appear with some of the other, already mentioned monsters on a variant cover by Benjamin Dewey; that's a pretty wide swathe of Toho monsters getting at least a cameo in this book, then).

Tieri manages a bit of a twist ending after the more predictable conflicts between the pirates and the monsters play out, and Miranda's art, while not the best I've seen from IDW on these monster characters, at least seems to be able to handle both the human characters and the monsters adeptly, and it provides a decent sense of scale between such diverse groups of characters.

If you have an itch for Godzilla and friends in comics form, and, in particular, one for something a little more off the beaten path for the venerable, 70-year old franchise, then Here There Be Dragons ought to scratch it.

If you have an itch for Godzilla and friends in comics form, and, in particular, one for something a little more off the beaten path for the venerable, 70-year old franchise, then Here There Be Dragons ought to scratch it.

How To Read Nancy: The Elements of Comics in Three Easy Panels (Fantagraphics) Another book read specifically to prepare for Nancy Fest—authors Paul Karasik and Mark Newgarden will be presenting on their book as part of the goings-on—I wasn't entirely sure if I should include this in the column or not, as, strictly speaking, it's not comics. I mean, the subject matter is comics, but it's not a work of comics, but a prose work about comics...although it does include 42 pages of classic Nancy strips at the end of the book, so it is, in addition to everything else, also something of a comics collection.

The meat of the book is it's 44 chapters analyzing the elements of a single Nancy strip, a three-panel affair from August 8, 1959. If that seems excessive, that seems to be part of the point of the book, which is both serious and humorous in its extreme rigor (Do keep in mind that the chapters are all very short, only several paragraphs long).

It's hard to imagine a more thorough examination of a single example of comics. Karasik and Newgarden isolate every single conceivable element of the strip, item by item, until it is as seemingly deconstructed as it can get. That the strip can bear such scrutiny is a testament to how complex cartoonist Ernie Bushmiller's work really was; it may be possible, but it's hard to imagine this same scrutiny being applied to, say, Garfield, for example. (Although much of what is applied to Nancy here can, and probably should, be applied to one's close-reading of any comic and should be of particular interest to those in the business of creating comics, although it's difficult to imagine one managing to keep all of this in mind when drawing comics. Some of it, one imagines, must be intuitive).

There's far more to the book than just this critical exercise, though. After various introductions and preambles, it opens with a 45-page biography of sort of Bushmiller, one that pays close attention to the development of the comic strip as a medium in the young cartoonist's early years and on Bushmiller's development as an artist (Up until the publication of Bill Griffith's Three Rocks, above, this was probably the most thorough examination of Bushmiller's biography).

There are also 18 appendices illustrating various topics brought up throughout the proceedings, including one exhaustive, exhausting examination of the hose gag, which goes on for some 20 pages and includes just as many examples of it appearing in previous comics. And then, of course, the comics collection, which is labeled "DO IT YOURSELF!" and is named after a do-it-yourself book gag in one strip from 1974.

"The forty-tow lessons of Nancy, August 8, 1959, that have been extracted in this volume's analysis can profitably be applied to most, if not all, comics," the pair write at the beginning of this section. "To emphasize each of them, the strips in this section have been selected as exemplary. Now it's your turn to connect the blacks, measure the horizon lines, and size up the panels."

What follows then is a highly curated selection of comics, each page given a suggested element to examine, such as "The Gag," "The Dialogue," "The Background" and so on. The beauty of Bushmiller's strips, of course, is that one need not do any such examining to enjoy them. They just work, whether you take a scalpel to them the way Karasik and Newgarden do, or if you just read them the way you always have.

Highly readable despite its scholarly bent, How To Read Nancy is a book anyone who engages with comics, be they classic newspaper gag strips or graphic novels, would benefit from exposure to.

As it turns out, Kawai actually reciprocated Tadano's feelings, but she recognized that he was going through a phase at the time (and we get to see rather a lot of that phase play out here), and if she accepted his declaration of love at that point it would only prolong his phase. Wanting him to grow out of it and better himself, she turned him down...for his sake.

And now they meet once again, and not only has Tadano successfully grown out of his phase, but he has Komi as a girlfriend. Thus starts a bitter rivalry between the two beauties, one that Tadano is mostly left unaware of.

As a love triangle, this one is maybe a bit less interesting than the earlier one with Rumiko Manbagi, given how similar Komi and Kawai are, but then, their similarity to one another does differentiate this turn of events from the earlier ones in which Komi found herself competing for Tadano, and now, of course, she's in the position of defending her relationship status with him, rather than trying to secure it in the first place.

Tomohito Oda's high school comedy remains a lot of fun, even as it passes its 300th chapter, and completes its 29th volume.

Predator Versus Wolverine (Marvel Entertainment) Marvel acquired the Predator license, long held by Dark Horse Comics, in 2022, but this late-2023, early-2024 many-covered, four-issue miniseries pitting the alien hunter against the publisher's best-selling mutant character is the first time they did what would seem to be the obvious thing with the license, cross it over with members of their long list of huntable characters.

Club Microbe (Drawn and Quarterly) Following her similar The Mushroom Fan Club and The Bug Club, the ever prolific Elise Gravel goes microscopic for another hybrid picture book/comic book in which she enthusiastically shares a favorite subject of the natural world with young readers. More here.

Winnie-The-Pooh (Drawn and Quarterly) I had mixed feelings about cartoonist Travis Dandro taking on the venerable nursery classic and adapting it into a comic now that author A.A. Milne's work has fallen into the public domain. But one can't really argue with results. If it was going to be done, this was the way to do it. More here.

DC, for instance, never held the Predator license, but had a pretty good working relationship with Dark Horse, and so over the years they had Predator hunt Batman (not once, but three times), Superman, the entire Justice League and, rather goofily, Batman, Superman and the Aliens.

An event series in which the Predators set their iconic, three-red dot sites on the various heroes of the Marvel Universe seemed like a smart, or at least highly marketable move. That, or at least a series of "vs." books like this one, with Predator Vs. Daredevil, Predator Vs. Spider-Man and so on. Perhaps they will eventually go that route, and Predator Versus Wolverine is just the first meeting between one of the alien hunters and a Marvel hero. To date though, all we've got are a series of variant covers and this Wolverine crossover.

It's the work of writer Benjamin Percy and seven different artists and it is, somewhat surprisingly, not all that great.

I say "somewhat surprisingly", while I suppose some of you with more sophisticated tastes than I are not the least bit surprised, because of the potency of the original Predator premise established in 1987—big game hunter from beyond the stars comes to Earth to hunt the most dangerous game of all—and just how easily it can be applied, formula style, to just about any action-adventure comic template, simply by swapping in a new hero as the designated prey. In addition to the DC heroes mentioned above, it's been fairly successfully used to pit some version of the Predator character against Judge Dredd, Tarzan, Magnus Robot Fighter, Witchblade and even the cast of Archie Comics.

Wolverine, then, would seem an easy enough fit, and certainly not as big a reach as, say, Archie Andrews.

The problem is that Percy's tale is a bit more ambitious than the simple application of the hunter/prey scenario that has dominated Predator crossovers to date. Rather than just having the bad guy and the hero fight and maybe meditate on the nature of hunting, he posits a century-plus relationship between Wolverine and one particular Predator, who this comic refers to as an alien species known as "the Yautja." (I'm assuming the name comes from somewhere other than this comic though, which is branded with a "20th entury Studios" logo in the upper right corner; personally, I think the more mysterious the Predators are left, the better.)

The book opens in the Ken Lashley-drawn "Present Day," during which a very badly injured Wolverine—you can see his exposed humerus, like a cartoon bone, jutting out from a bunch of scorched flesh—is on the run from a Predator with a distinctive set of claw marks on its shiny, silver, mail-like mask. He narrates in his native tough-guy talk, flashing back to the year 1900, when he first met this opponent (During which the first of the many "guest" artists takes over for a sequence. First up? Greg Land. Real talk? If I knew Land were drawing/inserting photo-reference part of this book, I probably would have just skipped it entirely).

This, then, establishes the format of the book. Wolverine battles the Predator in the present, while flashing back to a past encounter with the Predator and others of its kind, each past battle coinciding with a different status quo in the long-lived Wolverine's colorful life (and each of these drawn by a different artist, including Andrea Di Vito, Hayden Sherman, Kei Zama and Gavin Guidry).

And so the Predator hunts a young, turn-of-the-century Wolvie on the Candian frontier; he and some serious back-up returns to take on the mind-wiped, "Team X" Logan (in scenes that recall the jungle-set, Predator vs. team of army guy alpha males of the original film); he fetches "Weapon X" from the facility where he's kept (see the cover);he fights a sword-wielding Logan and Muramasa in Japan; and, finally, he launches a full-scale invasion of the Westchester manor and rather quickly and decisively gets his ass-kicked by the assemblage of mutants that have Wolverine's back (and so quickly as he might have had other mutants been present, though; I'm not expert enough at X-history to know when exactly this happened, but I bet a fan could pinpoint it based on Kitty's costume).

All in all, then, the Predator is very patient, and has the rather weird, or at least convenient, luck to come back for Wolverine's skull only when the character has entered into a brand-new, quite distinct status quo. I suppose, had the series been six issues instead of four, we might have also seen the Predator go after "Patch" in Madripoor or invaded Stark Tower to find the New Avengers protecting their teammate Wolverine.

Sure, it defies logic a bit—never more so than when Wolverine decides to set-up one final confrontation with the Predator and he does so simply by baiting him with his mask on a stake; just how the Predator knows to come look for it in Canada at that particular time is left unexplained—but, on the other hand, it keeps the narrative interesting, and the rotating artists similarly keep a reader's eyeballs entertained (It could certainly have been worse; Land could have drawn the whole series).

Ultimately Wolverine's plan for once and for all defeating a character that turned out to be one of his oldest archenemies—move over, Sabretooth—is kind of silly. Despite all of his friends, allies and resources, Wolvie decides to just go at the Predator man-to-man, claw to claw, just as he did in his first fight with it, 124 years ago. That Wolverine wins isn't a surprise, although the way he wins is kind of weird. Basically he and the Predator deliver mortal wounds to one another at the same time, prompting the Predator to set his self-destructing nuclear arm-band to go off while the two are still claws-deep in one another. Thanks to his healing factor, Wolverine's body grows back and restores him to life. The Predator's body remains dead.

Ultimately Wolverine's plan for once and for all defeating a character that turned out to be one of his oldest archenemies—move over, Sabretooth—is kind of silly. Despite all of his friends, allies and resources, Wolvie decides to just go at the Predator man-to-man, claw to claw, just as he did in his first fight with it, 124 years ago. That Wolverine wins isn't a surprise, although the way he wins is kind of weird. Basically he and the Predator deliver mortal wounds to one another at the same time, prompting the Predator to set his self-destructing nuclear arm-band to go off while the two are still claws-deep in one another. Thanks to his healing factor, Wolverine's body grows back and restores him to life. The Predator's body remains dead.

Thus Wolverine won not by proving himself a better hunter or fighter, or being more adept at the Predator's own game than the alien hunter itself was, as Arnold Schwarzenegger's Dutch in the original film did, but simply by having mutant powers. It took a lot longer to get there, then, but the conclusion was never in any more doubt than if the Predator fought, say, The Hulk; The Hulk would win, because he's got super-powers.

An interesting enough attempt to graft the Predator onto Wolverine's long, complicated history, but the story was ultimately a disappointing one.

The story is followed by six pages devoted to showing off a gallery of variant covers, from the likes of Mike McKone, Steve McNiven, InHyuk Lee, Adam Kubert, While Portacio, Gary Frank, and even Dan Jurgens and Bill Siekniewicz. These are mostly generic-ish images of the two characters locked in one-on-one combat, with only Peach Momoko's and Skottie Young's covers really sticking out, given how different their styles are from those of the more traditional superhero artists.

Before we move on, can we talk about the one panel that really struck me in this volume?

During the first issue, in the Land-drawn "Young Wolverine" sequence, there's a scene where the newly-arrived Predator, who doesn't seem to suffer at all from the extreme cold, despite the species' canonical preference of extremely hot weather, goes about killing various forms of wildlife, not unlike the sequence where the Predator in 2022 film Prey did the same.

He kills a deer, and then, on one three-panel page, engages other forms of wildlife: He leaps toward a bighorn sheep, he dodges as a mountain lion leaps at him and, most strikingly, he poses astrde a killer whale, a spear in his hand.

I am honestly a big more interested in a Predator vs. a killer whale than I am in a Predator vs. Wolverine...or any human (or, I guess, mutant) hero. In fact, for the longest time, that was "my" Predator story. A Predator comes to the Arctic, where the cold itself is a challenge to its very survival, fights a polar bear, and stalks some native human hunters, until he comes across an orca skull, and decides to hunt the world's actual deadliest prey—not Arnold Schwarzenegger, Batman or Wolverine, but a fucking killer whale, a 20-foot-long, three-to-four ton, apex species whose home is in an entirely different element than the one any Predator is accustomed to moving in, let alone hunting in. That, my friends, is Earth's ultimate prey.

Sadly, Percy found his way to the same idea, but all we get in terms of exploration of it is a Land drawing of Predator posed upon a small-looking photo of an orca amid that weird effect that happens when Land tries to convey water. Presumably, this Predator bested the orca, or at least fought it to a standstill. How on Earth did he accomplish that? Percy leaves it to our imaginations.

Small surprise that the same Predator survives an attack by a grizzly bear—a timely attack that saves the young Wolverine and scars the Predator's face-mask—given that it managed to fight a fucking killer whale earlier in the story.

Personally, I would have liked to see more of that then Samurai Wolverine vs. Predator and the like.

REVIEWED:

Monkey King and the World of Myths: The Monster and the Maze (G.P. Putnam's Sons) Cartoonist Maple Lam remixes the story of Sun Wukong into her own, unique, unifying cosmology, and mashes it into the Greek story of the Minotaur and the labyrinth for a fun adventure that reinvents the myths that inspired it. More here.

No comments:

Post a Comment