Millions of Cats

This is probably Wanda Gág’s signature work. It's the book most often cited as an example of her work, at any rate.

Originally published in 1928, it won a Newbery Honor Award in 1929, which is of course awarded for distinguishing contribution to children’s literature. Newbery Awards are not often awarded to picture books, as the Caldecott Medal (first awarded about a decade after Millions of Cats saw print) is specifically devoted to picture books. (Gág would win a second Newbery in 1934 for ABC Bunny, discussed below; she also won two Caldecott Honor awards for Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and Nothing At All in 1939 and 1942, respectively).

Millions of Cats also established a format for Gág’s books that a few others would follow almost exactly, including the horizontal, landscape format in which images would sometimes snake across both open, facing pages in a spread, and the image itself winding and flowing across that space to simulate movement or simply a rolling landscape.

The story is a perfect little fairy tale, complete with a “Once upon a time” opening:

Once upon a time there was a very old man and a very old woman. They lived in a nice clean house which had flowers all around it, except where the door was. But they couldn’t be happy because they were so very lonely.The very old woman decides that a cat is just what they need to feel less lonely, and so the very old man sets out to find her one (leading to one of the many two-page illustrations, showing the old man walking a long trail over hills and valley, a quilt pattern-like landscape below him, and a trail of puffy white clouds in a strip of black fleck-suggested sky above him.

Finally, he comes to a hill that “was quite covered with cats,” leading to the first use of a rhythmic, song-like passage Gág returns to several times in the story: “Cats here, cats there, Cats and kittens everywhere, Hundreds of cats, Thousands of cats, Millions and billions and trillions of cats.”

Finally, he comes to a hill that “was quite covered with cats,” leading to the first use of a rhythmic, song-like passage Gág returns to several times in the story: “Cats here, cats there, Cats and kittens everywhere, Hundreds of cats, Thousands of cats, Millions and billions and trillions of cats.”The very old man sets about shopping for the prettiest cat, and just one he thinks he’s found it, he notices another one with some particularly pretty and unique aspect, and so he takes that one as well. Eventually, the millions and billions and trillions of cats go home with him.

That is a lot of cats. Even for a cat person.

That is a lot of cats. Even for a cat person.As you can probably guess, that many cats lead to some problems, particularly when they began to quarrel over who is the prettiest cat, which leads to an all-out cat war in which they apparently all eat one another (a rather grim detail perhaps, but one of the many markers of the story that indicate it was inspired by the märchen of Gág’s youth and old country, and that she would devote herself to translating and illustrating in her Tales From Grimm and More Tales From Grimm).

I won’t spoil what happens next, and I hope it’s not spoiling things too much to note that it ends happily ever after,

although Gág chooses not to end it with those words, but instead with a final, novel repetition of the “millions and billions and trillions of” phrase.

although Gág chooses not to end it with those words, but instead with a final, novel repetition of the “millions and billions and trillions of” phrase.

The Funny Thing

Gág followed Millions of Cats with The Funny Thing, which is similarly formatted and similarly reads like a classic fairy tale, albeit a very idiosyncratic one.

The protagonist isn’t the title character, but Bobo, “the good little man of the mountains.” He lives in a cave, and sets out food for the birds and animals, specific to their tastes: nut cakes for the squirrels, seed pudding for the birds, cabbage salads for rabbits and so on.

Then the title character arrives and complicates Bobo’s system. The Funny Thing, which looks “something like a dog and also a little like a giraffe,” and has a long tail and blue points along its back, and it isn’t any type of animal, but instead, it insists, an aminal.

Then the title character arrives and complicates Bobo’s system. The Funny Thing, which looks “something like a dog and also a little like a giraffe,” and has a long tail and blue points along its back, and it isn’t any type of animal, but instead, it insists, an aminal. And it is hungry.

It turns its nose at all of the treats in Bobo’s spread, in a series of lovely drawings in which the strange beast melodramatically refuses each with haughty posture and offended expressions, revealing what it most likes to eat: dolls.

When Bobo objects to the eating of dolls by saying he would think it would make children very unhappy to have their dolls eaten.

When Bobo objects to the eating of dolls by saying he would think it would make children very unhappy to have their dolls eaten.“So it does,” said the Funny Thing, smiling pleasantly, “but very good they are—dolls.”

Bobo tries to come to terms with its diet, and tries to rationalize it, “perhaps you take only naughty children’s dolls,” Bobo asks, and the Funny Thing, replies, “No, I take them specially from good children.”

Unable to countenance a monster that eats only the dolls of especially good children, Bobo launches a plan, which involves inventing “jum-jills,”something he hopes will be even more delicious than the dolls of good children.

There’s much less action in this story than in most of Gág’s other picture books, even ABC Bunny, but the art is exceptionally lively, with the double-page spreads illustrations used to illustrate the twisty interior of Bobo’s deep but homey cave and a few images in which the illustrations seems as carefully constructed as they are drawn, such as the one near the front in which the various animal species come to enjoy their treats, and one near the end where a fire-brigade formation of little flying birds and The Funny Thing’s long tail form long, long lines twisting in opposite directions.

In two sequences the picture-to-word ratio flip-flops dramatically, with a large illustration devoted to just a handful of spoken words of dialogue, such as when Bobo attempts to sell his aminal visitor on the virtues of his various animal treats, and another near the end in which The Funny Thing tries his first plate of jum-jills (I was so charmed by the story that I would attempt to come up with a recipe to make them, but cheese in one of the main ingredients, and thus jum-jills violate my strictly vegetarian diet).

In two sequences the picture-to-word ratio flip-flops dramatically, with a large illustration devoted to just a handful of spoken words of dialogue, such as when Bobo attempts to sell his aminal visitor on the virtues of his various animal treats, and another near the end in which The Funny Thing tries his first plate of jum-jills (I was so charmed by the story that I would attempt to come up with a recipe to make them, but cheese in one of the main ingredients, and thus jum-jills violate my strictly vegetarian diet).

The ABC Bunny

This 1933 picture book reveals the depth of talent in the Gág family, and that while eldest daughter Wanda Hazel was the one who grew up to be the most successful and famous, her own talents and interests were steeped in a particularly creative household.

Gág has written and drawn the book, and the title page reads “Hand Lettered By Howard Gág,” her younger brother, and the “ABC Song” that appears with notes and lyrics before and after the main text of the story, bears the notations “Music By Flavia Gág,” one of Wanda’s five younger sisters.

The song isn’t the one preschoolers learn to sing (I can’t read music anymore, but I noticed the lyrics could be sung to that tune, although I suppose it’s such a simple tune that anything can be sung to it), but is the story of a bunny and a little adventure he has. It’s the story that the book tells.

Each page features a big, gray-and-paper colored drawing which accounts for about half of the space on the page, given a generous border of white space above and to its sides. The bottom quarter or so of the page contains a large red capital letter (the only color in the book) and a phrase making some prominent use of the letter, and a part of the story.

For example, the first spread features a close, focused drawing of an apple hanging heavily from the bough of a tree, and the text “A for Apple, big and red,” while the facing page shows a sleeping rabbit in a nest of grasses, the apple swaying in the bunny’s direction, with the words “B for Bunny snug a-bed.”

For example, the first spread features a close, focused drawing of an apple hanging heavily from the bough of a tree, and the text “A for Apple, big and red,” while the facing page shows a sleeping rabbit in a nest of grasses, the apple swaying in the bunny’s direction, with the words “B for Bunny snug a-bed.”The story continues in such fashion, with the next spread showing an image of the rabbit jumping from bed as the apple falls to the ground (Gág drawing a sort of comet trail of white space around it to illustrate the motion of the fall) and the words “C for Crash! D for Dash!” and on the next page we see the bunny springing down a little lane, a pointing sign on a crooked post reading “ELSEWHERE,” while the text reads “E for Elsewhere in a flash.”

Along his journey, and the alphabet, he encounters various challenges and meets other animal characters, before finally arriving at his home town in a valley.

As for the more challenging letters, Q is for quail, X is “for exit—off, away! That’s enough for us today,” (the words stretched below images of a group of rabbits leaping into their holes), Y if for “You, take one last look (below an image of a child reading a book and using the Y of the word You as a book holder) and Z is for “Zero—close the book!”

Compared to some of her other books, the images in ABC Bunny are quite large (both in the publisher’s presentation—I’m looking at an edition published by Coward-McCann, Inc of New York from what seems to be 1977 or ‘78—and in relation to the amount of page-space devoted to words and white space on each page.

The art, all gray and seemingly drawn with either pencil or fine charcoal, is rather dark, and the animal characters bear quite representational forms, with great attention paid to their fur and feathers, even if their eyes and gestures betray the animation of a human-like intelligences within them.

The art, all gray and seemingly drawn with either pencil or fine charcoal, is rather dark, and the animal characters bear quite representational forms, with great attention paid to their fur and feathers, even if their eyes and gestures betray the animation of a human-like intelligences within them. The settings are all quite covered in similarly rendered, realistic looking foliage, although in many cases the plants are applied with a decorator’s eye, like pencil-gray frosting flowers on an elaborate birthday cake of imagery.

Snippy and Snappy

This tale of two little field mice, brother and sister, is a 1931 book in Gág’s horizontal, landscape picture book format.

The two siblings are drawn almost identically, with only the frill on Snippy’s waistcoat distinguishing her from her brother Snappy. The pair “lived with their father and mother in a cozy nook in a hay field…Snippy and Snappy liked this big grassy hay field and played in it all day long.”

On one day, the pair are out playing with a big ball of string or yarn that belongs to their mother, Mother Mouse. It’s human-sized, rather than mouse-sized, and is therefore quite large. They roll it that so far away that they eventually have to stop and take a nap, at which point a human child picks up the ball and wanders off with it.

On one day, the pair are out playing with a big ball of string or yarn that belongs to their mother, Mother Mouse. It’s human-sized, rather than mouse-sized, and is therefore quite large. They roll it that so far away that they eventually have to stop and take a nap, at which point a human child picks up the ball and wanders off with it.They have no choice but to follow the child, and it leads them to a human home, which the mice have never visited, but only heard their dad, Father Mouse, talk about, whenever he would read aloud to them from his newspaper.

“This newspaper was small enough for a mouse to read,” Gág writes, “and it was called THE MOUSE PAPER.”

Our little heroes have some interesting adventures in the house, which is presented as especially mysterious and exotic, effectively enough that the everyday seems a bit more magical to the reader when filtered through the mice’s eyes (and, no doubt, the decades since the story was written).

They also encounter a quite grave danger to mice, and come very close to meeting their ends, but, so you don’t worry too much about their fates between now and the time you read the book for yourself, I will tell you this—they survive and live happily ever after. Actually, they “lived happily ever, ever, ever after,” as Gág writes, echoing a poetical use of “never never never never”, formatted in a little stairway of words, on the very last page of the book.

As you can see from the cover, the book features the same rolling landscapes that Millions of Cats did, and there is a bit of walking and traveling in it, usually over such little hills.

Gone Is Gone; or, The Story of a Man Who Wanted to Do Housework

Gone Is Gone; or, The Story of a Man Who Wanted to Do HouseworkThe gender politics of this 1935 story might seem pretty out-of-date, as does the assumption that men do a certain kind of work and women do another kind of work, but do consider that non only was it published in 1935, it is, Gág wrote in a little introduction, “an old, old story which my grandmother told me when I was a little girl. When she was a little girl, her grandfather had told it to her, and when he was a little peasant boy in Bohemia, his mother had told it to him.”

The edition I’m looking at is a tiny, child’s-sized book, akin to the Beatrix Potter books I read when I was small, and still occasionally see old copies of in libraries. It’s about four-and-a-half-inches across, six-and-a-half-inches high, and a quarter of an inch thick, and the cover is golden yellow with orange and black, as most of the Gág books I find.

Also unlike some of the others in this little bibliography I’m compiling, it is not written in Gág signature, hand-written font, but in type.

The pictures are all quite small, and none sprawl from one page to the next, but are set purposefully and comfortably within single pages; sometimes filling them entirely, other times occupying part of the space on a page, which will otherwise be devoted to bearing the text of the story.

The man who wanted to do housework is Fritzl, a farmer and father. He is married to Liesi. They each work very, very hard, with Fritzl tending to the farming, while his wife cleaned, cooked and cared for the baby.

“They both worked hard, Fritzl always thought he worked hard,” Gág writes, and so one night when he dismisses her work with a “All you do is to putter an dpotter around the house a bit—surely there’ sn othing hard about such things,” Liesi suggests that the next day they trade duties.

Fritzl learns the hard way that housework actually is hard work, as little mistakes lead to big, spectacular disasters. Whenever something goes wrong, like the dog Spitz running away with the sausages when Fritzl turns away, he shrugs off the loss, saying “Na, na! What’s gone is gone.” That’s where the title comes from, and that’s what Fritzl says more than once throughout his disastrous day as a housekeeper.

Gág’s art style is instantly recognizable, but looser and more exaggerated than in some of her other works, with the animal characters especially behaving in a somewhat cartoonish fashion.

Gág’s art style is instantly recognizable, but looser and more exaggerated than in some of her other works, with the animal characters especially behaving in a somewhat cartoonish fashion.

There’s an extremely interesting afterword about the story, which the title page says is “Retold” by the artist, and which her introduction says was passed down from generation to generation in her family.

There’s an extremely interesting afterword about the story, which the title page says is “Retold” by the artist, and which her introduction says was passed down from generation to generation in her family.According to Gág, “Gone is Gone” was her favorite märchen growing up, and she just assumed it was one of the tales the Grimms had collected. Later in her life, she would go on to translate and illustrate two collections of the Brothers Grimm’s stories, and in this afterward she notes, “I could hardly wait to come upon that old peasant fairy tale of my childhood. To my surprise and disappointment, it was not in Grimm at all.”

She had found a story sort of similar, and talked to other people who remember similar stories from their youth, but the version she grew up hearing wasn’t committed to paper yet, and so she “decided to make a little book of the story, consulting no other sources except one—my own memory of how the tale was told to me when I was a little girl.”

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs

Gág’s picture book version of the classic fairy tale came out the year after the Disney movie, a movie that was so popular that it can be kind of hard for those of us born into a post-Star Wars pop cultural landscape to even comprehend.

Gág’s Snow White must have proved quite a contrast with Disney’s though, as it follows the original so much more closely. In fact, the words of it are that of the original, albeit here translated by Gág herself. Certain elements seen in the movie remain here, but if you’ve only seen the movie, then this one might seem a bit more strange, as it reduces the roles of the dwarves, who are nameless and identical, and increases the role of the evil queen, who makes several magical attempts on Snow White’s life before succeeding with the poisoned apple.

It opens with the story of how Snow White’s mother conceived of her before physically conceiving her and how she got that name, before the bit with the mirror, the jealousy, the instructions to have Snow White killed, the dwarves, the witch-attacks and so on.

Gág’s illustrations are all smallish, black-and-white, and charmingly simple. Only a few take advantage of the page to great effect—like an almost-full-page image of the Queen posed with a peacock before here mirror, or an actual full-page illustration of Snow running into the woods, watched by animals hidden among the plant-life—and the work is thus more that of an illustrated prose storybook, rather than a picture book of the sort we normally think of when we hear that word.

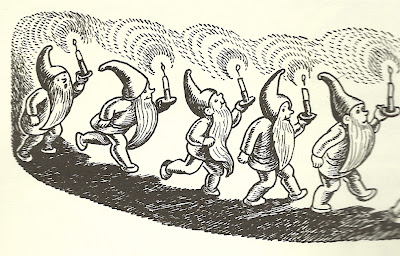

Gág’s illustrations are all smallish, black-and-white, and charmingly simple. Only a few take advantage of the page to great effect—like an almost-full-page image of the Queen posed with a peacock before here mirror, or an actual full-page illustration of Snow running into the woods, watched by animals hidden among the plant-life—and the work is thus more that of an illustrated prose storybook, rather than a picture book of the sort we normally think of when we hear that word. Among Gág’s particular design choices of note here are her quite child-like version of Snow White—who is short and plump and pre-pubescent looking compared to the Disney teenager and the adolescent Snow Whites who have followed—and her dwarves with long, white beards, erect, pointy caps and simle, matching peasant garb, all of whom more closely resemble the image most of us get when we hear the word “gnome” today, thanks in large part to Wil Huygen and Rien Poortvliet’s gnome book and lawn gnomes.