Buddy is a big, angry, hungry, furry, orange, striped monster, first seen on the end pages, running through the forest, knocking down trees and roaring "Rahhhhh!" He proceeds to run and roar through the title page and indica and into the story itself, yelling "Outta my way, trees!" and "Dry up, lake!" and so on at everything he passes. He eventually stops when he finds a trio of little white bunnies, each shaped like mittens with two thumbs, with ears, faces and cotton tails attached, playing checkers. Buddy tells him that he's going to eat them.

The bunnies are bummed out, as they were just about to make cupcakes.

Now Buddy may be a monster, but he's not a monster: He lets the bunnies make their cupcakes first, deciding to eat the bunnies for dessert, and he plays hide-and-seek with them while the cupcakes bake. When the cupcakes are ready, Buddy eats nine of them, and is then too full to eat the rabbits.

He returns the next day to eat the now five little white bunnies, but they again have another, more fun activity planned, and Buddy joins them, failing to eat them once again.

This goes on for several days: Buddy shows up to eat the bunnies, but the bunnies change his mind through some form of distraction. On the third day, Buddy starts to notice there are more bunnies each time he arrives. This isn't integral to the story, but makes for a pretty funny riff on the fact that rabbits are always multiplying.

You can probably guess the resolution, as it's the title of the book. When the bunnies have run out of tricks and Buddy is ready to finally eat them, they happily tell him that he's not supposed to play with his food, which is what he's been doing for days! This makes Buddy realize that the bunnies must not be his food after all, and thus no one gets eaten. (Well, no one that isn't a cupcake, anyway.)

So it's a little like the story of Shahrazad, only with playing substituted for storytelling. As with Dinosaur Vs. Bedtime, I imagine this is a particularly fun story to tell to children one-or-one or in largish groups, given that it involves lots of yelling and roaring.

And as with the last few books of Shea's of read, including Unicorn Thinks He's Pretty Great, it's full of beautifully, deceptively simply-rendered looking art, super-cute designs, remarkable cartooning and brilliant colors that make every page look like something that should be hanging on one's wall, rather than just lying there between the covers of a book, where visitors will have a harder time seeing those pages.

Buster, The Very Shy Dog (Houghton Mifflin; 1999): I'm pretty sure there's a saying about judging books by their covers, but I'm equally sure it's meant as a metaphor in which books represent people, and that in actuality it's generally not that bad an idea to judge books by their covers. Certainly one can judge picture books by their covers, right?

I'm going to say yes, and Buster, The Very Shy Dog is my example of why this is okay.

It was the cover that got me to pick this book and take it home. I liked the juxtaposition of the title with the image, in which we see a dog so shy that he seems a little anxious to even be on the cover of a book about himself, and is sort of cautiously sneaking onto it, and only then because there appears to be some cake and ice cream there to coax him onto the cover.

It's a cute, funny drawing by writer/artist Lisze Bechtold. And what do you know, the book, like the cover, is full of cute, funny drawings!

The book contains a trio of super-short stories starring Buster, the new addition to a family that already has a dog who is his opposite in ever way, in her personality as well as in her visual depiction. Plus, they had three cats. These other pets were not shy, they were bossy.

The first is "Buster's First Party," in which there is a birthday party at their house, which makes it exceptionally hard for Buster to find a place to hide, as he usually does.

Eventually he finds a little girl who is sitting by herself, not having any fun at all, and he slowly approaches her and puts his head on her lap.

That's followed by "Buster and Phoebe," about Busther's relationship with the older, bolder Phoebe, in which Buster discovers the one thing he's actually better than at Phoebe, something he demonstrated in the previous story: He's a good listener.

And finally there's "Buster and Phoebe Meet the Garbage Bandit," in which the two dogs team-up to find out who it is that is disturbing the family's garbage cans every night (Not to brag or anything, but I solved the mystery by the time I read the title and saw the garbage cans: It's totally raccoons.

Like a good comic, Buster derives its comedic power and/or charm from the interplay between the words and images, the latter of which often illustrate a particular example of what the words say, without the words having to spell it all out.

A Child’s Book of Angels (Barefoot Books; 2000): I’m not entirely sure who this book is for, and/or what age of child would most appreciate it. I would have been interested at about any point in my life before the onset of adulthood, I guess, for the same reasons I was interested in mythology, demonology and any and all writings about fairies and monsters: The sense of a large body of ancient but new-to-me knowledge, the system of order and classifications.

In fact, that’s why I picked it up and brought it home, even though now that I’m an adult and these areas of knowledge seem less forbidden, less secret, less occult to me: On a flip-through, I saw a listing of the classic order of angels, something that used to fascinate me as a little kid, when angels were just angels, and I didn’t know there were different kinds. You know, Seraphim, Cherubim, Thrones, Dominions, etc.

The book is written Joanna Crosse and rather lavishly—I’d even say overly—illustrated by artist Olwyn Whelan.

It’s awfully, even surprisingly New Age-y. The story, which is really just a framework upon which Crosse can lay out a bunch of information about angels, is that Matt, a young boy who suffers from nightmares, is talking to his mom about guardian angels before bed one night. He wishes he could see at meet his guardian angel and, no sooner does his mom turn out the lights, then he does: The angel Muriel is sitting on his bed, and takes him on a flight around the universe, introducing him to various angels of various kinds and functions.

They start with an explanation of the zodiac and its angels, and then move on to astrological signs. From there, it’s planetary angels, and then the aforementioned hierarchy, and a sort of animism, in which every thing has an angel of its own, from seasons and healing, to birth and death, to cities and houses, to plants and animals. Of these, Crosse includes “Devas,” who work hand in hand with “Many helpers, such as fairies, elves, brownies, sylphs and ondines.”

The book is also surprisingly non-committal about any religious articles of faith, as when Muriel answers Matt’s question about where the stars and planets come from with, “Nobody really knows”…surely this angel has read or had access to a science textbook right? Or could at least commit to a “God created them.” Or split the difference with “Some say this, others say that.” Teach the controversy, Muriel! (Not that there is a controversy; if there are all these angels, there’s gotta be a God, right? And God can be the author of the creation of the stars and planets, whether its described as magic or a scientific process).

Muriel never talks about God, but does say Creator-with-a-capital-“C” once. When discussing death, there’s a rather New Age-y passage about shedding the heavy overcoat of life and “all dying leads to new life,” and a “next cycle of existence.”

Reading, I was pretty constantly curious about Crosse’s sources, and she does helpfully include a two-page listing of 17 sources, but not in a rigorous, instance-by-instance way, and they all seem like secondary, tertiary or even further removed sources, with names like An Angel a Week, A Dictionary of Angels, Encyclopedia of Angels and so forth (and some titles that sound like they would only be found on the bookshelves of a New Age store, like Working with Angels, Fairies and Nature Spirits and The Crystal Healer).

Each page is packed with extremely colorful artwork, much of it quite elaborate in design, with borders around the pages and detailed patterns on the angels’ robes. It was flat and suggestive of ancient artwork, but fully-painted with gradiated shades of water-colors; I don’t now if the term “baroque Tomie de Paolo” means anything to anyone but me, but that’s what I thought while looking at many of the pages.

Clever Cat (Alfred A. Knopf; 2000): Peter Collington's book is a rather humorous story, but it's also a fable of sorts, premised as an explanation for why cats seem so lazy and why they are so helpless, relying on their human owners for just about everything—all while examining exactly what makes a cat clever or not. His highly realistic, painted art really sells the humor, as his cats look so much like real cats, so when the protagonist, Tibs, begins exhibiting human-like behavior, the absurdity is underscored. (I didn't care for many of his humans though, simply because they seemed so representational).

Tibs is a pretty typical cat, waiting every morning outside his front door for one of the humans he lives with to let him in, and then standing in the middle of the hall, waiting to be noticed and fed breakfast. Finally, after every other family member rushes past, late for school or work, Mrs. Ford notice hims and says, "Why can't you feed yourself,you great fat lump? You always make me late."

Sick of always waiting for the humans to feed him, and perhaps taking Mrs. Ford's words to heart, one day he climbs up to the cupboard, takes down a can of cat food, opens it with a an opener and standing on his hind legs, eats it from a plate and spoon.

Impressed with how clever Tibs is, Mrs. Ford gives him his own front door key and, the day after that, a cash card, as she forgot to buy him cat food, but he seems clever enough to go buy his own.

The neighbors see Tibs walking home on his hind legs, carrying two cans of cat food, a house key and a cash card in his front paws, and remark that they wish they had a clever cat like Tibs, rather than the lazy cats they have, who just lay there sunning themselves. Those cats simply wink at each other: Perhaps they know something the reader doesn't?

Tibs gradually becomes more and more a cat of the world, dining in cafes, going to the movies and so on.

Eventually, the Fords take the cash card back and sit him down for a talk. Since becoming clever, Tibs has also become expensive, so they tell him he needs to get a job, and pay rent. He gets a job as a waiter at the cafe he likes, and he soon finds himself living exactly like a human: Working long, hard hours, and turning over most of the money he earns for rent and bills, so that he's left with only enough money to buy himself cat food to eat.

Arriving late for work one day, he loses his job, and the Fords aren't happy (There's an illustration of the scene where he's told that he must find a new job immediately by his masters-turned-landlords that is both hilarious and heartbreaking, as he covers his eyes with his little cat paws while showers of tears pour out of them).

Then he notices all those other cats dozing in the sun, and realizes what it is exactly that makes a cat clever. And so he plays dumb again, and goes back to his life of leisure, where his only problem was having to wait for someone else to feed him.

Goldilocks and Just One Bear (Candlewick Press; 2011): Leigh Hodgkinsons' riff on Goldilocks and the Three Bears starts out as a pretty simple reversal of the classic story, with a bear—wearing boots and a scarf—getting so lost that he soon finds himself no longer in the woods, but in a noisy, scary, confusing big city. He flees the street to find refuge, and ends up in an apartment in the Snooty Towers building. He's hungry and tired, and looks for something to eat and somewhere to rest, where he repeats Goldilocks' patterns in the home of the three bears—sort of.

"This porridge is too soupy," he says while dipping his spoon in the fish bowl. "This porridge is too crunchy," he says while spooning up cat food from the dish on the floor labeled "Le Chat."

When he dozes off in a just-right bed, three blonde human beings come home—a daddy person, a mommy person and al little person. Mid-way through the human family's freak out, the book takes a rather unexpected twist, when (spoiler warning!) the bear thinks the blond mommy person looks a little familiar to him, and the blond mommy person thinks the whole accidentally wrecking-the-joint sceneario seems familiar to her:

"Baby Bear?" said the mommy person.And so it was that the grown-up Goldilocks and the grown-up Baby Bear were reunited under strangely coincidental circumstances. After the family serves the bear some porridge, they send him on his way, with a map back tot he woods.

"Goldilocks?" said the bear.

Hodgkinson's art is extreely charming, flat, simple and rough in design, but very busy and very colorful, with an almost collage-like quality to the juxtaposition of coloring and textures in the various objects in the fuller panels.

I'm a Frog! (Hyperion; 2013): The first thing one notices about Mo Willems' latest Elephant & Piggie book is the uncharacteristic contraction in the title, the I'm in I'm a Frog! rather than an I am. Perhaps due to their being books for starting readers, these rarely if ever have the characters speaking in contractions, which was, for me at least, at first somewhat off-putting, but the grand, emphatic way in which the characters spoke eventually became part of the humor (Scanning the list of other Elephant & Piggie titles at the back of the book—19 already!—I see one other has had a contraction in the title, Let's Go for a Drive!, while I Am Invited to a Party!, I Will Surprise My Friend and others eschew contraction opportunities).

So the plot of this one is that Gerald the elephant is surprised one day when Piggie hops over to him ribbit-ing and, when he questions her behavior, she explains that she is a frog (Contrary to her name, her appearance and what Gerald knows of her).

She explains that she's pretending to be a frog, and most of the book is taken up by her trying to explain the concept of pretending to Gerald, who is hearing it for the first time (contrary to the events of some other books, but whatevs, let's not nitpick continuity in standalone starter reader books; that's much more fun with superhero comics).

There's a nice, sharp bit where Gerald seems somewhat alarmed by the concept of pretending. "You can just go out and pretend to be something you are not!?" he asks, and, when Piggie assures him that everyone pretends, he follows up with, "Even grown-up people?"

Piggie looks out at the reader, her eyes narrowed and one eyebrow raised, as she says out of the side of her mouth, "All the time." Gerald, follows her gaze, looking at the reader, a single eyebrow raised in curiosity.

The concept of pretending eventually makes sense to Gerald, and he joins in, in one of those neat little almost-twist endings Willems excels at in these books. But the grown-ups diss is probably the the most noteworthy aspect of the book, a little bit of fourth-wall breaking meta-commentary of the sort that permeates We Are in a Book!.

Lines That Wiggle (Blue Apple Books; 2009): This book written by Candace Whitman and drawn by Steve Wilson is on a subject integral to art: Lines. The verbal component is pretty simple, a sing-songy, rhyming delineation of various types of lines. "Lines that wiggle, lines that bend, wavy lines from end to end," and so on.

Each page is a sort of standalone, poster or print-like image with brilliant bright colors of a limited variety per page; there's little texture or depth or detail, but the subject matter is fun, funny and of particular subjects of great interest to me. Mostly monsters really; in addition to the monster eating spaghetti on the front cover, there's a giant black monster sitting atop a rainbow, a giant monstrous foot that makes a school bus detour around it, and a trio of Bigfoot monsters captured in a net:

There's a giant octopus, a mummy, a horse wearing a cowboy boots, and a big, bipedal cat walking a bunch of little daschunds on leashes. In fact, there isn't a page in the book that I wouldn't like to see in poster form, hanging on a wall.

Each page features a shiny, slightly raised line, that runs across the page, and is integrated into the art, allowing one to follow the lines with the finger as well as the eyes. I don't know if its meant to be an art book or not, but it can certainly be read as one: Both as a collection of great, individual art images by Steve Wilson, and as a sort of basic how-to guide, in terms of identifying and classifying that basic component of drawings. "Lines are everywhere you look," Whitman concludes, "so find some lines not in this book!"

Little Owl's Orange Scarf (Alfred A. Knopf; 2012): Tatyana Feeney introduces us to Little Owl, a little owly who lives with his mom in a tree in Central Park. After we learn a little bit about Little Owl and his likes, we learn something that he doesn't like, his new orange scarf that his mom had made him. Not only was it orange and itchy, it was very, very long (so long, that it extends across three pages when we first see it).

Little Owl tries very hard to lose his scarf, and he finally succeeds on a class field trip to the zoo.

I love this image of his mom calling the zoo, as it is the only instance where some object or item that the owls have or use is of human rather than owl proportions.

So Little Owl's mom has to make him a new scarf, so this time they work on it together, which makes for a nice bonding experience, and also means that Little Owl gets to add his own input, meaning he gets a scarf he like: Blue, and appropriate in length. (And there's a neat revelation of how he finally managed to get rid of his too-long orange scarf on the last page).

Feeney's art work is wonderfuly simple, seemingly done with sparse pencil lines on white pages, with just very sparse bits of blue, orange and grey coloring throughout (For example, their little triangle beaks are orange, Little Owl has a few blue feathers, while his mother has a few gray feathers, and so on).

The lettering isn't hand-lettered, but it is big and blocky, and blue in color, looking as if it were (mechanically) filled in with blue lines, as if the artist were coloring in the white space of the block letters.

It's a really beautiful-looking book, the simplicity of Feeney's art only accentuating that beauty.

The 108th Sheep (Tiger Tales; 2007): This gorgeous republication of a 2006 British book by artist Ayano Imai concerns the practice of counting sheep to fall asleep, as the cover no doubt suggests.

The main character is a little girl named Emma who can't fall asleep, and drinking warm milk and reading didn't do anything to help. She finally turns to counting sheep, and one by one a big, fluffy sheep—each shaped a bit like a lop-sided egg, with a little black head and weird, realistic sheep eyes and tiny black sheep legs sprouting from the orb of wool—appears and leaps over the high headboard of her bed. Each is stamped with a red number, making counting all the easier, and even this doesn't work as she hoped, as she gets all the way up to 107 without dropping off:

"There goes 106," she said. "And there's 107. And now here comes..."Not-so-hot at high-jumping, the 108th sheep can't make it over the headboard, which is a big problem for everyone: I guess they can't jump out of order, and the sheep can't go to sleep until they finish their job and, for that to happen, 108 has to get over the headboard.

There was a thud, and Emma's bed shook slightly.

The 108th sheep did not appear.

Emma and the sheep collaborate on different methods for helping 108 get over, which Imai draws without explaining each, letting the pictures handle the explanations for her, and Emma ultimately comes up with a solution that find her and the 100+ sheep all curled up snugly and asleep in her bedroom.

The book is a big, square one, far too big to fit on my scanner, and the pages are of a wonderful texture that a more knowledgeable writer about books could probably name to you, but all I can say is that each page was full of little grooves, and it felt a bit like wall paper to me.

Imai's artwork is all in pencil, with the quite delicate individual lines all clearly visible. Each cream-colored page has a red-paneled border in the middle, with the picture appearing within that panel. These are black and white and a little bit of red; or, actually, they are paper-white and pencil-gray, with the numbers on the sheep appearing in the same deep red as the panel borders, and a slightly lighter red coloring Emmas's rosey cheeks.

It's quite a beautiful-looking book, from the art to its format and construction, and the story it tells is pretty charming.

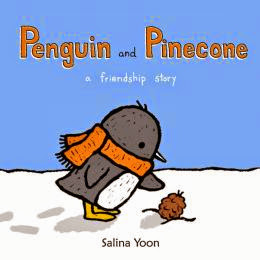

Penguin and Pinecone: A Friendship Story (Walker & Company; 2012): Salina Yoon's penguin character, Penguin, finds a pinecone in the snow one day. Penguin has never seen or met a pinceonce before, and doesn't know what it is, but he recognizes it as cold, so he sits down and knits it a little orange scarf like the one he wears. They happily play together, until Pinecone sneezes, and Penguin's Grandpa tells him that the pinecone, Pinecone, belongs in the forest, and so Penguin takes his friend to a pine forest and leaves it there.

Later, Penguin returns to find that his friend has grown up into a big, strong pine tree, easily identifiable by the orange scarf tied around its upper branches. They hang out and play in Pinecone's home turf for a while, but that environment is no better for Penguin than the snowy Antarctic was for Pinecone, so Penguin leaves.

There's a little overly direct moral at the end—"When you give love...it grows"—but it's accompanied by a very neat image of a whole forest of pinetrees, many of them wearing little pieces of winter clothing, to designate them as pinecones that befriended penguins (when Penguin first returns home, he accidentally brought a new pinecone with him, and a female penguin befriends it; on that last page, we see a tree wearing a boot around its trunk and a bow atop its boughs that match her own boots and bow).

The artwork, as you can tell by that on the cover, is darling.

Penguin on Vacation (Walker Books; 2013): Salina Yoon's Penguin returns to make a new friend in this book, in which he decides he needs a vacation ("Snow again?", he asks, comic book style). For a change of pace, he decides he wants to go somewhere tropical, so he leaves his scarf with his grandpa, packs a suitcase, and rides a gradually melting ice floe to a tropical beach.

He quickly discovers that the environment is pretty foreign to him, and his normal activities can't be replicated in a sandy environment. Then Penguin makes a new friend, Crab, who teaches him how to have fun at the beach.

Eventually, Penguin needs to go home, so he sits on his luckily buoyant suitcase, and Crab stows away, saying "I need a vacation too!" So Penguin gives Crab a little green scarf and matching mittens, and he shows him how to enjoy the snow and ice. It's pretty similar to Penguin and Pinecone in its cultural exchange, and just as cute.

Santa and the Three Bears (Boyds Mill Press; 2000): I read this, and I'm writing these few paragraphs about it, after I read the next book discussed in this post, despite the fact that this beat it to market by some 13 years. Despite coming first, it is a less elegant and less obvious admixture of the story of Goldilocks and the Three Bears with the story of Santa Claus. Here, the three bears-a papa, mama and baby polar bear—intrude upon Santa's house while he's away on Christmas Eve, doing his thing, and Mrs. Claus and the Claus' three elf helpers have gone out to get a Christmas tree.

The bears wreak havoc in Santa's cottage, but make restitution after Mrs. Claus finds them all sleeping in the Claus' bed—she puts them to work, fixing the damage they caused.

Writer Dominic Catalano presents a rather rustic Santa, unmoored somewhat in time—sometime after the invention of the electric Christmas lights—giving the book a classic feel, and his Santa and Mrs. are decidedly elfin in their own appearance, with long, pointy ears and noses.

Santa Claus and the Three Bears (Harper Collins; 2013): Writer Maria Modugno has come up with a pretty simple idea for a story, a Christmas twist on a fairy tale classic that pretty much tells its whole story right there in the title.

Modugno doesn't even mash up A Visit From St. Nicholas and Goldilocks and The Three Bears so much as she subtracts the little blonde from the latter, and adds Santa Claus to replace her. The other major tweaks of the story are to change the species of bear from the more generic brown bear to polar bears, and to holiday up the details.

So it's the night before Christmas and the three bears—big Papa Bear, middle-size Mama Bear and wee little Baby Bear—are getting ready for the holiday, decorating the house, putting up the tree and baking. When they sit down for their Christmas pudding, they realize it's too hot to eat, so instead of putting ice cubes in it like sensible bears, they decide to go for a walk to look at the Christmas lights in the neighborhood.

Meanwhile, Santa comes down the chimney, tries the three bowls of pudding, sits in the three chairs and, tuckered out after all that work, tries all three beds. The Bear family returns to find him sleeping in Baby Bear's bed, but rather than running off, as the little girl trespasser generally does, he gives them each a present, in a flip-flopped size order, so that Baby Bear gets the great big present, Papa Bear gets a little present and Mama Bear gets a medium-sized one.

The illustrations are provided by Jane and Brooke Dyer, and really make the book. Their polar bear family is a highly civilized one, obviously, as they live in a house with furniture and all, but theirs is still a rather rustic life, with Papa Bear having a big, stiff chair made from thick birch branches, for example, and their decorations being all-natural: garlands of holly and berries, and icicles that Papa Bear carries in a back-basket and somehow attaches to the house. Their Santa is similarly old-school, looking like the fat, little, old elf described by Clement Clark Moore, rather than a more modern, post Coke advertisement Santa Claus.

No word on what the bears thought when they watched those

Santa’s New Suit (HarperCollins; 2000): Writer/artist Laura Rader’s charming Christmas picture book opens a week before Christmas, with Santa Claus looking into a closet and deciding he doesn’t have a thing to wear (We’ve all been there, I suppose).

Not only is it full of nothing but identical red suits with white fur trim and matching hats, they all show signs of some serious wear-and-tear. I suppose centuries of around-the-world winter night flights and going up and down millions of chimneys will do that.

“I need a change,” he announces to Mrs. Claus, and tells her that he’s going to go buy a new suit. After a brief sequence in town where he visits various stores, he finds what he’s looking for at a store named The Snappy Dude.

Unfortunately, no one seems as enamored of the new suit as Santa, with typical reactions at the North Pole being “Oh my!” and “Egads” and “Yikes!” It doesn’t work outside the arctic circle either, as no one recognizes Santa without his trademark suit, which I suppose is as much as a uniform at this point as anything else. Obviously, things turn out as one might expect, and by Christmas Eve Santa Claus is back in his more familiar outfit.

The message is perhaps a negative one if you think too deeply about it—for Santa, clothes really do make the man, and he finds himself bound to the status quo, beset on all sides by peer pressure to dress to others’ expectations of him—but that’s probably just a thirtysomething’s too-close reading of the book, which is really much more focused on the humor of presenting a very familiar figure with an extreme change, and exploring the ways in which the world might react.

Snowy Valentine (Harper; 2012): You know David Petersen as the creator of the winning comic Mouse Guard (and the drawer of occasional covers for books like Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Fraggle Rock and The Muppets), did you know he's also responsible for at least one children's picture book?

Well, he is.

Though the cute, anthropomorphic woodland creatures on the cover of this book are rabbits rather than mice, it's immediately and abundantly clear that this is the work of the same artist.

The story, which Petersen has conceived and written as well as drawn, is so simple that to say too much about it at all is to risk ruining it. On a snowy Valentines Day morning, Jasper Bunny sets out from his home atop a hill, intent on thinking of the perfect gift with which to express his feelings for his wife, Lilly. He decided to visit his neighbors for ideas.

He visits the Porcupines and The Frogs, stops by a flower cart run by Everett (A raccoon), wind sup in some trouble when Teagan Fox invites him in to his den to brainstorm, and has a brief chat with a cardinal before returning home. Metaphorically, the journey itself proves his love for Lilly and, in its doing, he inadvertently created a big, unmistakable, visual sign of his love for her.

Rather than the medieval setting of his Mouse Guard comics, these animals seem to live in a more modern period in the past, perhaps a comfortable, Victorian village in Europe or perhaps the United States. In the setting, realistic rendering of human-like animals, and their dress and manners, Petersen's book evokes the work of Beatrix Potter. I have to assume that Petersen's wife Julia, for whom he made the book (the dust jacket says) was quite pleased with her Valentine's gift that year.

Tea Rex (Viking; 2013): Get it? Tea Rex? Like a T-Rex, but here the "T" refers to the beverage, and is not an abbreviation for "Tyrannosaurus"...?

Well, I laughed.

There's not much more to the joke than what Molly Idle has put right there on the cover: The clever play of words, the huge dinosaur sat awkwardly but gamely with two little kids at a children's tea party, but that's actually plenty.

Inside, Idle's words are instructional in nature, explaining how one is to host a tea party:

When hosting an afternoon tea for a special friend—greet your guest at the door. Lead him through to the parlor. Introduce him to your other guests—and offer him a comfortable chair.

And so on. The images feature the little girl hosting the tea, Cordelia, and her more little still brother or friend, going through each of these steps with their guest, a very polite Tyrannosaurus who wears a little polkadot bowtie and carries a tiny hat with his tail.

The difficulty of doing each of these things when a dinosaur is involved is illustrated, and is often in sharp contrast to the quiet, polite tone of the writing. For example, the words "Lead him through to the parlor" appear on a two-page spread in which the dinosaur strains and sturggles to fifth through the door, while Cordelis pulls on one of his little arms, and her friend or brother pulls on her shawl.

A few pages later, the instructions "Take Turns making small talk..." lead off a four-page sequence in which 1) Cordelia babbles on about the weather and her begonias while the boy looks bored and the dinosaur points at his watch, 2) The little boy says "Ta-daaa!" as he hangs a spoon from his nose, and 3) the T-Rex says "ROAAAAAR!" and and blows everyone off the pages.

It's delightful.

Yeti, Turn out the Light! (Chronicle Books; 2013): Next to the last two Shea books, this is probably my favorite picture book that I've read in quite a long while, not simply because it features a Yeti as its protagonist or because artist Wednesday Kirwan (who obviously had pretty cool parents) had produced such wonderful artwork, contrasting the bestial reputation of the maybe-real-but-probably-not monster with a mundane, domestic setting and drawing some of the cutest woodland creatures imaginable.

No, what I really like about it is the look on the Yeti's face. That's not anger; that's just the face the Yeti always makes, no matter what he's doing.

On the first page, we see the Yeti standing on a cliff, holding a large stick, shielding his eyes from the sun as he looks out over an idyllic valley, where a pair of deer drink from a stream. The rhyming narration tells us that the Yeti's day is just about over, so he returns to his home, carrying the stick over his shoulder (no idea what he does with that stick all day). That home in the side of a cliff, and accessible by a bright red door, complete with a door knob, keyhole and hinges—hard to believe Bigfooters have been unable to find any sasquatches or yeti,given such a tell-tale sign to where they might live. Why, it couldn't be any easier to spot, not unless he put out a welcome mat and erected a mailbox reading "Yeti" on it.

After he eats dinner and flosses and crawls into bed, Yeti is already to drift off to sleep, when suddenly he sees strange, scary shadows on the wall. He turns on his beside lamp only to discover that they are....

...adorable bunny rabbits.

They join him in bed, but on on the next page, another strange shadow appears, scaring Yeti and the bunnies, and yet again it turns out to be an adorable set of woodland creatures, so arranged that their shadows look scary in the dark. This happens a few more times and, eventually, Yeti kicks all the animals out, and everyone goes to sleep in their respective homes.

I'm not a big fan of the rhyming storybook, but writers Greg Long and Chris Edmundson do an okay job of it here, and it was somewhat inspired to make the child-like character easily frightened at bedtime be a monster himself, and for basing a whole book around the common childhood phenomenon of turning the least threatening objects into monstrous things when the lights go out.

But mostly what I admire about this is Kirwan's art. And her Yeti face and expressions, which change very, very little from emotion to emotion.

1 comment:

Thanks, Caleb! Helped a lot with some birthday gift shopping.

Post a Comment