For example, a collection of Mark Martin's three issues of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, in their original black and white, sells for $7, whereas the IDW collection featuring the exact same contents only (poorly) colorized will run you $17.99.

Here's what I got, and, as always, what I thought...

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles #45: The sewer-dwelling mutant alligator Leatherhead should be something akin to a cousin of the Turtles. Not only is he a reptile, but he became an anthropomorphic one thanks to exposure to the same mutagenic compound of the TCRI aliens that mutated the Turtles and Splinter. The character made his first appearance in a 1987 issue of the original volume of Tales of The Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, and in this one-off issue by Dan Berger, he returns.

Like a lot of the issues of TMNT from this period—this was 1992, and still five issues away from the epic, 13-part "City At War" mega-arc that closed out the first volume of the series—how and where this particular story fits into the greater Turtles story is ambiguous, as our heroes are in New York City, and fighting remnants of the Foot Clan when the story begins.

Berger opens with a quite conscious three-page homage to Eastman and Laird's Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles #1, including a two-page splash in which he "covers" that from the characters' first appearance. His Turtles are big and blocky, and have a great deal of texture and shadow about them (Leatherhead's creator, cartoonist Ryan Brown, is credited with tones on the book). His most notable innovation is in Raphael's teeth. I suppose he was going for an evil grin of some sort ("I feign insanity," he narrates the opening fight scene, "Makes it more fun for me, an' it gives Leo justification for my..."BEHAVIOR"), but he gives Raphael about ten times too many teeth (well, it was the '90s), so he looks like he's got the mouth of a mutant baleen whale).

The opening scene is a deliberate echo of the Turtles' fight with The Purple Dragons, but here they are fighting Foot ninja. As is explained afterwards, the Foot are in disarray after the (second) death of The Shredder, and there's something of a ninja crime wave currently effecting the city. One of the Foot soldiers then takes over narrating, and we get the story of four Foot (these ones wearing different and differentiated costumes), as they flee the Turtles only to end up in Leatherhead's clutches.

They agree to help the alligator man complete his "Transmat Device," with which he hopes to teleport himself to his human family (he need nimble human fingers to perform some of the work). Together, the Turtles and Foot help him, but it's all for naught: His machine blows up, leaving Leatherhead swearing vengeance on everyone involved.

It's an extremely talky, and somewhat silly story, but it fits in nicely with the ongoing Foot plot, and, as is always the case with the Turtles comics of t is period, it's interesting to see different artists offer their own interpretations of the characters.

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles #46-#47: This two-part story is by frequent TMNT contributor Michael Dooney (#13, #27, a four-part contribution to the Turtle Soup mini, etc), and is, according to the introduction by publishers Eastman and Laird, inspired by Dooney's contribution to the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles Portfolio, which included nine color plates. Dooney's was of Leonardo dressed like a samurai, the ditzy timelord-in-training Renet (from #8, the Cerebus crossover) slung over his shoulder.

In fact, this story has an awful lot of continuity in it for a Turtles comic, as it not only features Renet and the evil time lord Savanti Romero, but also Hattori, from TMNT #7 (the "Pre-Teen" Mutant Ninja Turtles issue, where the characters had different masks and used different weapons).

The plot of the story, "Masks," involves Hattori coming to the Massachusetts farmhouse, suffering from something that Splinter's mystic ninja arts tells him involves someone attempting to change the past in a way that effects Hattori's ancestors. Enter Renet, who Dooney draws sans cape or funny helmet (so basically just in a bathing suit), and writes in her original, more Valley Girl conception. She takes the Turtles back in time to set things right and what, exactly, was setting things wrong?

Another time-displaced, reptile-man: An anthropomorphic dinosaur samurai named Chote, who serves a mysterious lord whose identity I've already spoiled.

Dinosaur samurai vs. regular samurai! Ninja turtles vs. samurai! Ninja turtles vs. dinosaur samurai! Renet and Romero, the latter dressed in a new, 14th century Japanese costume for much of the proceedings! All drawn by Dooney, one of the all-around better TMNT artists, as he had his own distinct style, but not one that was so radically different from that of Eastman and Laird that the style overwhelmed the story and took focus from the characters.

And, on the subject of samurai, these issues must have been published just as Mirage was gearing up to publish Stan Sakai's Space Usagi miniseries, as #46 included four pages of Sakai's sketches and design work, and #47 included an eight-page story entitled "Hare Today, Hare Tomorrow," in which a scientist friend of the Usagi of the future's machine accidentally pulls the original Usagi Yojimbo out of a battle with ninjas and into the present...temporarily.

Reading "Masks," I was reminded of reading something one of the Turtles' two creators said around the time that the computer-animated TMNT movie came out (so I'm assuming it was Laird), how they never intended for The Shredder to become the sort of Darth Vader of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles universe. Which makes sense; they did kill him off in the very first issue (Although he returned, sort of, in Leonardo #1, and that return explained in the "Return to New York" storyline and...that was pretty much if for The Shredder in the original volume of the Mirage series and related publications, right? Three stories? Only one of which featured the real Shredder, the other two bizarrely created worm-colony clones?).

By contrast, Savanti Romero appeared in TMNT #8, Tales of the TMNT #7 and this two-issue storyline. That's three times as many appearances as that of the "real" Shredder (He would also appear in the next volume of Tales of... too, but then, so to did worm-colony clone Shredder). I found myself wondering, given his more frequent appearances, why Romero was never a villain of any great import in later or extra-comics appearances of the Turtles—there have now been five feature films, for example, three of which feature The Shredder and zero of which feature Romero—but, just as I was wondering, I answered my own question. Because The Shredder was the guy in the cartoon, duh.

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles #48: This issue marks a pretty major turning point in the story of the original Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles story, being the first part of a two-issue prelude to the 13-part "City At War" storyline that closes out the original volume of the series, and finds a more-or-less stable creative team in place, with Kevin Eastman and Peter Laird once again heavily involved. Here they're credited with the story, while Laird and pencil artist Jim Lawson share the script credit, with Keith Aiken inking (and A.C. Farley providing the cover).

The characters are doing something of a routine training mission. Casey Jones gets a three-hour head-start to hide somewhere in the nearby city of Springfield, Massachusetts, while April drives the Turtles into town and drops them off. An elaborate game of ninja hide-and-seek, they have until 1 a.m. to find Casey and get a ride home and, if they lose, they have to hike all 20 miles back.

Things go really, really wrong when a trio of young thugs try to mug him in a playground (why they chose to pull a knife on a big guy wearing a hockey mask and a golf bag full of sporting equipment with which to hit them, I don't know). Casey accidentally hits one of the kids a little too hard, and kills him, something that should happen in superhero comics on a fairly regular basis, but pretty much never does, one of those little conceits of the genre readers just have to learn to accept if they're going to read the damn things (Casey in particular should probably being killing people left and right, given he's an untrained vigilante whose weapons of choice include hockey sticks, baseball bats and golf clubs; bashing in the heads of ninja assassins seems a little more acceptable than street criminals).

Local vigilante Nobody, a costumed vigilante who is a police officer by day and who previously met the Turtles in an issue of Tales of..., tries to bring Casey down for the crime, but the Turtles intervene. The pay-off for all of this, and a few panel interlude in which April's truck breaks down and a stranger offers to help, will come in the next issue, where the makeshift family unit of the Splinter, The Turtles, April and Casey will break apart, drifting into four different directions for "City At War."

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles/Flaming Carrot Crossover #2-#4: I read the first issue of this series in 1993, and then the comic shop in my home town either folded or didn't order the rest of the story, so I never found out what happened next. Until now!

Despite the title, The Flaming Carrot plays a relatively small role in the proceedings, as he is just one of the many Mystery Men characters who appear in the story, characters who would go on to get their own bad movie with a great cast in 1999 (Beating the X-Men to the silver screen by a year!).

Despite the title, The Flaming Carrot plays a relatively small role in the proceedings, as he is just one of the many Mystery Men characters who appear in the story, characters who would go on to get their own bad movie with a great cast in 1999 (Beating the X-Men to the silver screen by a year!).The first issue of the story, entitled within as "The Green Flame," featured the two teams journeying to South America independently to investigate strange goings-on in the jungle. Bizarre little creatures made entirely of green fire were sighted, and a team of scientists went missing. The Turtles are here working with the U.S. military, which is obviously pretty weird, but presented in a purely matter-of-fact way, while the Mystery Men are of independent superhero team, like a highly-dysfunctional Justice League.

The story is...well, it's not much good, to be honest. I enjoyed the first issue in large part because it was my first introduction to the weird-ass Mystery Men characters—The Shovelor, The Spleen, Screwball (who scans an awful lot like the modern Deadpool without guns), Star Shark, Mister Furious, etc—but once the story gets going in earnest, it's fairly random and meandering in its plot, and the Turtles are for the most part superfluous to the story, and play roles that any of the other Mystery Men easily could have played.

The plot basically boils down to this: A bunch of crazy shit happens for four issues. Which, fair enough, the comic does have "Flaming Carrot" in the title, so that's works well enough. But having waited over 20 years for the conclusion, it obviously didn't live up to what I was expecting (That said, if IDW republished this, and included the original TMNT appearances from Flaming Carrot's own comic, I would totally buy that trade).

The plot basically boils down to this: A bunch of crazy shit happens for four issues. Which, fair enough, the comic does have "Flaming Carrot" in the title, so that's works well enough. But having waited over 20 years for the conclusion, it obviously didn't live up to what I was expecting (That said, if IDW republished this, and included the original TMNT appearances from Flaming Carrot's own comic, I would totally buy that trade).The creative team for the first issue was a pretty much ideal one for the endeavor: Flaming Carrot creator Bob Burden wrote it, and TMNT artist Jim Lawson drew it, with Mary Woodring coloring the art (and doing a damn site better than whoever colorizes those IDW collections does). By the second issue, however, artist Neil Vokes takes over some of the drawing, and Eric Vincent the coloring, with Vokes and Vincent handling all of issues #3 and #4.

I like Vokes' work just fine, but it's a pretty jarring change from that of Lawson, and it seems unusual to find this sort of thing on a small-press book like this, as, in my mind at least, I tend to associate it with DC Comics' recent attempts to never miss a shipping date (unless its a Jim Lee-drawn book), no matter how many different artists have to draw a single issue (Say, did anyone read New Suicide Squad #2 this week? One artist did layouts, and four others did finishes; and that's a 20-page comic!).

The Collected Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles Vol. 2: The specific issues of the original TMNT run collected in this book—#12, #13 and #14—were among Holy Grail-like ones to me when I was a teenager, just setting out reading and collecting comics. These issues were among the few that were new enough that they weren't collected in the fairly massive Vol. 1 (which collected the first 11 issues, plus the four "micro-series" one-shots), but were old enough that I could never, ever find them in back-issue bins.

It was therefore quite a pleasure to finally get my hands on this collection, which included those early but not that early issues of the series. Plus I've always dug that evocative A.C. Farley cover, of the Turtles scaling a building, Raphael already at the top, with his mask down.

The first of these is an all Peter Laird issue (with Steve Lavigne providing the lettering), in which Splinter, April, Casey and the Turtles are enjoying a picnic in their still-new, rural, post-Leonardo #1 farmhouse existence. They're interrupted by a lost and hysterical grad student, who manages to sputter enough about his crazy, survivalist militia captors before being shot by one of them to put the fear of nuclear armageddon into our heroes: Apparently, he has been forced to build a crude nuclear bomb for the bad guys.

The bulk of the issue is thus devoted to the survivalist hunting Splinter and the Turtles, who get to show off their ninja skills taking them down, before the bomb can be set off.

That's followed by Michael Dooney's #13, "The People's Choice," the first Eastman-less, Laird-free fill-in issue of the series (Lavigne once again provides the letters). I just recently wrote about this story when discussing IDW's collection of early Turtles comics in their colorized Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles Comics Classics #1. This is the one where the guys encounter a female politician/warrior from another planet who is pursued by another politician/warrior from another planet, where elections are settled by battle. As the second lady has four aliens to help her kill the first, the Turtles join in to even the odds. Unsurprisingly, it reads much better in black and white than the rather hurried, poorly done re-coloring job of the IDW collection.

The final issue is by Eastman and Talbot, and is a sort of gangster movie pastiche set in Northampton. Casey Jones, wearing a fedora and trench coat with his hockey mask, assigns himself a case: To find the missing cow statue torn from atop a local business. The case gradually involves April, who we learn is working as a waitress in town now (I always wondered what they did for money in the country; if they were just living off April's savings account or what) and the Turtles, who, before all is said in done, wear human clothes and hold guns...although they never actually seem to shoot them at anyone.

It makes for a pretty fun genre mash-up, as so many of the comics from this period seem to be interested in, and has a lot of characters, a lot of players and a lot of moving parts, making for a particularly meaty single-issue story.

Not included in the collection?

This pretty swell, if not exactly centered, wrap-around cover featuring the characters in gangster movie drag.

The Collected Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles Vol. 3: Say, is this cover image by A.C. Farley what inspired 1993 film Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles III? It sure looks like a more detailed, more serious version of the Turtles-as-samurai image from the movie's poster.

This slim trade collects three extremely different comics of the original series, by some rather different artists. Within are 1988's #15 and 1989's #17 and #18, each of which features a different setting and a different genre for the Turtles characters to rub up against and become enfolded by.

The first of these is Peter Laird's "Dome Doom," featuring inks by Jim Lawson, which is an honest-to-goodness, straightforward superhero story, the first of the series, predating Michael Dooney's one-issue story of Radical and Carnage in #27 by a year or so.

In it, Casey and a poorly disguised Raphael and Michaelangelo are in a comic book store, shopping and discussing other Mirage Comic Puma Blues, when some robots attack the joint: It seems the store is run by two former, retired superhereos, who used to run with the team Justice Force: "Stainless" Steve Steel and Metalhead.

The robots were sent by their old, aged enemy Dr. Dome, and the heroes convene their similarly retired teammates as Mike, Raph and Casey call up their teammates, and soon the action shifts to a house full of superheroes and vigilantes besiege with his robots.

The Turtles seem sort of out of place in the story, but they are meant to be. Aside from Metalhead, Laird's hero creations aren't terribly original or interesting—there's a stretchy guy, a speedster, etc—but the idea of a couple of former superheroes managing a comic book shop is rather inspired, and the friction between the most prevalent genre of American comics with the Turtles comic is just as fun as it's meant to be.

One neat thing about the book at this point, when Eastman and Laird were still contributing to various extents, was how different it would look from issue to issue, depending on who was penciling and who was inking. This issue stands in extremely sharp contrast to the next one collected here, as Laird and Lawson use relatively few lines, and the art looks very open, bright and airy, particularly considering that it's in black and white.

That next issue is drawn by Eric Talbot, and written by Talbot and Kevin Eastman. Entitled "Distractions," for a reason that will be obvious on the last page, it is essentially just a weird goof of a comic, in which a lone Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle—who turns out to be Michaelangelo—finds himself in a high-fantasy samurai narrative, complete with a wizard, in a land that evokes feudal Japan. It reads like a rather feverish mash-up of Lone Wolf and Cub and Conan, and while I loved it upon first reading some 20 years ago now, the story seems weaker and weaker with each subsequent reading.

Not that it necessarily needs to be all that strong, given the premise: The last page, a splash, features Mikey in his room at his desk, a stack of papers full of hand-writing next to him, a pen in his hand, as he rubs his head and asks his cat, "Well, that's the story so far, what do you think, Klunk—too corny?"

Talbot's artwork on the story, on the other hand, seems just as good, gritty, imaginative and exciting now as it did when I first read it. His art remains among my favorite of the series after Eastman and Laird's own, and this story in particular is full of meticulously inked and shaded imagery. It would be harder to imagine a story that visually contrasts more strongly with the previous superhero story. Without one of them being in color, of course.

The final issue is credited to Kevin Eastman and Mark Bode, though the credits go into no greater detail than that. The artwork is definitely that of Bode, and, according to comics.org, Eastman and Bode co-wrote the script, while Eastman and Talbot inked Bode's pencils.

A sort of unofficial Turtles/Bruce Lee team-up, this story, entitled "Shell of the Dragon," finds our four heroes traveling to China, where they immediately witness a restaurant being vandalized as part of the villainous gangster Beancurd's plan to force all of the area restaurants to use his dangerous and unnatural ingredients. The turtles intervene, just when Bruce Lee stand-in Chang Lee, the nephew of the restaurant's owner, appears.

Together the five of them take on the gang and, obviously, ultimately arise triumphant.

Bode's art is somewhat unusual for the series, although we are by now entering a point where "unusual" starts to become "usual" in the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles ongoing. Most of the characters who aren't Lee are extremely cartoony in design—just as much so as the title characters, really—and Bode does this neat thing where all of the sound effects and dialogue bubbles appear in the white space above each panel, so none of the words obscure any of the art.

It's a great deal of fun to see the Turtles in a setting, starring in what is essentially a comic book version of a kung fu movie. Bode would return to the title again in about a year's time, for 1990's #32, in which the Turtles journey to Egypt and do battle with Egyptian gods.

This single issue was also released as a color special, which is how I first read it.

The Collected Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles Vol. 5: This volume also includes three issues of the original Mirage volume of Turtles comics, which are among the weirder of those from the anthology-like era of the title. What binds the three issues—1988's #17 and 1989's #22 and #23—together is that all three are the work of Mark Martin, one of the more singular creators to have offered his own particular version of the Eastman and Laird's creations over the years.

In fact, the only bit of this collection not by Martin is the cover, which like all of those for the collected books, is drawn by A.C. Farley. It's interesting to see Farley's very particular, very realistic take on the turltes and Splinter sharing space with Martin's creations Dale Evans McGillicutty and Gnatrat on the cover, neither of whom look particularly close to Martin's designs for them (particular Dale).

All three comics are rather closely related, and all three are ones I had never yet read before, despite really loving the covers for all of them:

The first is narrated by little girl Dale Evans McGillicuty, who uses a rather neat looking time machine that resembles a flexible white cube to tell a fast-paced, light-hearted time travel story that cycles around a few times in a pretty fascinating way, and which the Turtles get swept up in. Martin draws them for the first time almost exactly as they appear on the cover Teenage Mutant Ninja Turltes #1 (complete with Donatello having a katana tucked into his belt wile holding his bo staff), and, after that first appearance in a large panel, their designs vary only rather slightly. In a way, Martin's Ninja Turtles are truer to Eastman and Laird's designs in the original comic than Eastman and Laird's are in the comics that followed it.

The following pair of stories more heavily involve the Turtles, as well as Splinter, Dale and Martin's own creation Gnatrat, a Batman parody who is an anthropomorphic rat who dresses in a gnat-themed costume (He's appeared in a handful of comics beyond these ones, none of which I've been able to track down).

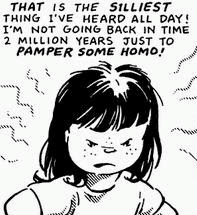

In the far-flung future of 1995, a strange, floating alien called a Skwal approaches Dale and tells her that the only way she can save Earth is travel back in time 2 million years to make life easier for Homo Habilis, which leads to an un-PC joke it might be harder to get away with today—

The Skwal's theory is that if life was easier for the humanity at the dawn of man, Earth might turn out to be a bettter, more peaceful, more paradisical world. Dale complies, and it turns out the Skwals were right, but their motivation was sinister: With Earth a peaceful paradise, it will be much easier for them to conquer. Dale then recruits The Fannywhacker, Gnatrat's truant officer identity in the new world (as truancy is the worst crime left to fight) to go back in time and un-pamper that homo.

Meanwhile, April receives a bomb-threat, and the Turtles tear the house apart looking for it, but to no avail...their bodies are destroyed in the blast. Splinter, who is a much more light-hearted, acidic and funny character here than usual, stores their brains in robot bodies while he repairs their physical bodies using his secret Eastern mystic arts, and they must fight a little crime while in those cobbled-together robot bodies.

They also spend some time reverted back to normal turtles, after Dale "fixes" Earth for the Skwals to invade, and before Gnatrat can un-fix it.

Much of the second half of the story involves Gnatrat recruiting his friend Splinter—independent comics anthropomorphic rat characters apparently all knew each other in the late-eighties—to help him return to his own time.

It's all pretty silly stuff, but still well within the acceptable level of silliness of your average TMNT story of the time. Those last two issues featuring Gnatrat are a pretty interesting example of a very organic Turtles crossover with a relatively minor character from the indie comics of their day. Everyone remembers Dave Sim's Cerebus and Stan Sakai's Usagi Yojimbo, but the likes of Martin's Gnatrat and Matt Howarth's Those Annoying Post Bros seem to slip through the cracks.

The Collected Paleo: Tales of the Late Cretaceous: There are no turtles in this trade paperback collection, unless one counts the archelon in book four, but this is nevertheless the work of the Mirage family of creators. It's the work of Jim Lawson, who has probably produced more pages of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle art than any other creator in the characters' 30-year-existence. He writes and draws every panel of every issue. But, in addition, Peter Laird assisted on inks on two of the six issues collected here, A.C. Farley designed the book, Laird and Farley lettered it and Michael Dooney painted over Larson to help provide the cover of the collection (and the usually quite beautiful individual covers of the series, which only appear in black and white within this all-black-and-white collection).

A dinosaur comic in the tradition of Ricardo Delgado's Age of Reptiles or S.R. Bissette's Tyrant, each issue of Lawson's Paleo tells the story of a different dinosaur—or prehistoric dinosaur contemporary—in a dramtic fashion, while trying to keep the temptation to anthropomorphize the characters at bay as much as possible. The "characters" have no names, no motivation beyond survival and no emotions or feelings beyond the more primal, animal ones of hunger, fear, pain, frustration, exhaustion and so on. Each issue is basically a sort of dinosaur documentary, necessarily extrapolated and dramatized rather than based on direct observation, but seemingly hewing fairly closely to more modern paleontological thought as it existed at the beginning of the 21st century.

In the first issue, a young female triceratops becomes separated from her herd by large Daspletosaurs and flees into the forest, where she encounters a series of dangers, and, at the climax, she faces one of them, and is saved by an unlikely "ally." The second focuses on a pack of raptor-like Dromeosaurs as they hunt and are hunted. The third features a young, bone-headed Stegoceras' short, tragic relationship with a Quetzalcoatlus following the death of his mother at the hands, foot-claws and jaw of a pack of Dromeosaurs. Book four stars a Plotosaurus, a huge sea-going mososaur, as it seeks prey in the shallows of the coast and the deep of the ocean, constantly competing with other large predators for every kill. Book five stars an aging Albertosaurus, who finds himself in a due-to-the-death with a fellow predator, a younger Tyrannosaurus. And, finally, in book six, we hear the entire life story of one of the era's most successful if smaller predators, a dragonfly (Lawson gets all of the protagonist species on to the cover of the book, though you'll have to look closely to see the dragonfly and the Plotosaurus).

With the exception of the final story, which gets some mileage out of the breathless narration suggesting a bigger, badder predator than the dragonfly that eventually emerges, and mmmaaayybe the fifth issue, which features some of the best writing, the stories could probably due without Lawson's narration, and the only thing that would really be lost would be the specific names of the specific species.

The storytelling, and the art, is that good.

Those who have only see Lawson's art on his Ninja Turtles books might be surprised by how it looks here, given the great degree of detail he invests in all of his prehistoric creatures, and the world they move through. It's really quite incredibly detailed, full of rich linework which, when paired with the lack of human and/or anthropomorphic character, removes it quite far from Lawson's usual work (The dinosaurs here are even more richly designed and rendered than other Lawson dinosaurs I've seen, like those in his illustrations for the Palladium RPG source book, Transdimensional TMNT).

These stories (the first five of which you can find serialized online here) are book-ended by two really great features.

There's a ten-page essay serving as an introduction to the book entitled "The Paleo Path: Paleo and the History of Dinosaur Comics" by Bissette, who knows a thing or two about dinosaur comics (and has the issues of Tyrant to prove it). In addition to singing Lawson's praises, he also offers a very thorough history of dinosaur comics, carefully separating comics with dinosaurs in them (in Lawson's case, that would include his early-nineties two-issue Dino Island and his kickstarted Dragonfly) from true dinosaur comics, featuring dinosaurs in realistic, human-free comics devoted solely to dinosaurs (Sticking with Lawson, Paleo).

And, in the back and labeled as "bonus material," is a short, six-page, wordless story in which two predatory dinosaurs, with the basic features of raptors, only of very small stature, fight. It's beautifully rendered, and much differently than all that proceeded it. It's told in reverse silhouette, with the figures and plant life all solid white, and the black ground all black.

It's a really beautiful piece.

Together the five of them take on the gang and, obviously, ultimately arise triumphant.

Bode's art is somewhat unusual for the series, although we are by now entering a point where "unusual" starts to become "usual" in the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles ongoing. Most of the characters who aren't Lee are extremely cartoony in design—just as much so as the title characters, really—and Bode does this neat thing where all of the sound effects and dialogue bubbles appear in the white space above each panel, so none of the words obscure any of the art.

It's a great deal of fun to see the Turtles in a setting, starring in what is essentially a comic book version of a kung fu movie. Bode would return to the title again in about a year's time, for 1990's #32, in which the Turtles journey to Egypt and do battle with Egyptian gods.

This single issue was also released as a color special, which is how I first read it.

The Collected Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles Vol. 5: This volume also includes three issues of the original Mirage volume of Turtles comics, which are among the weirder of those from the anthology-like era of the title. What binds the three issues—1988's #17 and 1989's #22 and #23—together is that all three are the work of Mark Martin, one of the more singular creators to have offered his own particular version of the Eastman and Laird's creations over the years.

In fact, the only bit of this collection not by Martin is the cover, which like all of those for the collected books, is drawn by A.C. Farley. It's interesting to see Farley's very particular, very realistic take on the turltes and Splinter sharing space with Martin's creations Dale Evans McGillicutty and Gnatrat on the cover, neither of whom look particularly close to Martin's designs for them (particular Dale).

All three comics are rather closely related, and all three are ones I had never yet read before, despite really loving the covers for all of them:

The first is narrated by little girl Dale Evans McGillicuty, who uses a rather neat looking time machine that resembles a flexible white cube to tell a fast-paced, light-hearted time travel story that cycles around a few times in a pretty fascinating way, and which the Turtles get swept up in. Martin draws them for the first time almost exactly as they appear on the cover Teenage Mutant Ninja Turltes #1 (complete with Donatello having a katana tucked into his belt wile holding his bo staff), and, after that first appearance in a large panel, their designs vary only rather slightly. In a way, Martin's Ninja Turtles are truer to Eastman and Laird's designs in the original comic than Eastman and Laird's are in the comics that followed it.

The following pair of stories more heavily involve the Turtles, as well as Splinter, Dale and Martin's own creation Gnatrat, a Batman parody who is an anthropomorphic rat who dresses in a gnat-themed costume (He's appeared in a handful of comics beyond these ones, none of which I've been able to track down).

In the far-flung future of 1995, a strange, floating alien called a Skwal approaches Dale and tells her that the only way she can save Earth is travel back in time 2 million years to make life easier for Homo Habilis, which leads to an un-PC joke it might be harder to get away with today—

The Skwal's theory is that if life was easier for the humanity at the dawn of man, Earth might turn out to be a bettter, more peaceful, more paradisical world. Dale complies, and it turns out the Skwals were right, but their motivation was sinister: With Earth a peaceful paradise, it will be much easier for them to conquer. Dale then recruits The Fannywhacker, Gnatrat's truant officer identity in the new world (as truancy is the worst crime left to fight) to go back in time and un-pamper that homo.

Meanwhile, April receives a bomb-threat, and the Turtles tear the house apart looking for it, but to no avail...their bodies are destroyed in the blast. Splinter, who is a much more light-hearted, acidic and funny character here than usual, stores their brains in robot bodies while he repairs their physical bodies using his secret Eastern mystic arts, and they must fight a little crime while in those cobbled-together robot bodies.

They also spend some time reverted back to normal turtles, after Dale "fixes" Earth for the Skwals to invade, and before Gnatrat can un-fix it.

Much of the second half of the story involves Gnatrat recruiting his friend Splinter—independent comics anthropomorphic rat characters apparently all knew each other in the late-eighties—to help him return to his own time.

It's all pretty silly stuff, but still well within the acceptable level of silliness of your average TMNT story of the time. Those last two issues featuring Gnatrat are a pretty interesting example of a very organic Turtles crossover with a relatively minor character from the indie comics of their day. Everyone remembers Dave Sim's Cerebus and Stan Sakai's Usagi Yojimbo, but the likes of Martin's Gnatrat and Matt Howarth's Those Annoying Post Bros seem to slip through the cracks.

The Collected Paleo: Tales of the Late Cretaceous: There are no turtles in this trade paperback collection, unless one counts the archelon in book four, but this is nevertheless the work of the Mirage family of creators. It's the work of Jim Lawson, who has probably produced more pages of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle art than any other creator in the characters' 30-year-existence. He writes and draws every panel of every issue. But, in addition, Peter Laird assisted on inks on two of the six issues collected here, A.C. Farley designed the book, Laird and Farley lettered it and Michael Dooney painted over Larson to help provide the cover of the collection (and the usually quite beautiful individual covers of the series, which only appear in black and white within this all-black-and-white collection).

A dinosaur comic in the tradition of Ricardo Delgado's Age of Reptiles or S.R. Bissette's Tyrant, each issue of Lawson's Paleo tells the story of a different dinosaur—or prehistoric dinosaur contemporary—in a dramtic fashion, while trying to keep the temptation to anthropomorphize the characters at bay as much as possible. The "characters" have no names, no motivation beyond survival and no emotions or feelings beyond the more primal, animal ones of hunger, fear, pain, frustration, exhaustion and so on. Each issue is basically a sort of dinosaur documentary, necessarily extrapolated and dramatized rather than based on direct observation, but seemingly hewing fairly closely to more modern paleontological thought as it existed at the beginning of the 21st century.

In the first issue, a young female triceratops becomes separated from her herd by large Daspletosaurs and flees into the forest, where she encounters a series of dangers, and, at the climax, she faces one of them, and is saved by an unlikely "ally." The second focuses on a pack of raptor-like Dromeosaurs as they hunt and are hunted. The third features a young, bone-headed Stegoceras' short, tragic relationship with a Quetzalcoatlus following the death of his mother at the hands, foot-claws and jaw of a pack of Dromeosaurs. Book four stars a Plotosaurus, a huge sea-going mososaur, as it seeks prey in the shallows of the coast and the deep of the ocean, constantly competing with other large predators for every kill. Book five stars an aging Albertosaurus, who finds himself in a due-to-the-death with a fellow predator, a younger Tyrannosaurus. And, finally, in book six, we hear the entire life story of one of the era's most successful if smaller predators, a dragonfly (Lawson gets all of the protagonist species on to the cover of the book, though you'll have to look closely to see the dragonfly and the Plotosaurus).

With the exception of the final story, which gets some mileage out of the breathless narration suggesting a bigger, badder predator than the dragonfly that eventually emerges, and mmmaaayybe the fifth issue, which features some of the best writing, the stories could probably due without Lawson's narration, and the only thing that would really be lost would be the specific names of the specific species.

The storytelling, and the art, is that good.

Those who have only see Lawson's art on his Ninja Turtles books might be surprised by how it looks here, given the great degree of detail he invests in all of his prehistoric creatures, and the world they move through. It's really quite incredibly detailed, full of rich linework which, when paired with the lack of human and/or anthropomorphic character, removes it quite far from Lawson's usual work (The dinosaurs here are even more richly designed and rendered than other Lawson dinosaurs I've seen, like those in his illustrations for the Palladium RPG source book, Transdimensional TMNT).

These stories (the first five of which you can find serialized online here) are book-ended by two really great features.

There's a ten-page essay serving as an introduction to the book entitled "The Paleo Path: Paleo and the History of Dinosaur Comics" by Bissette, who knows a thing or two about dinosaur comics (and has the issues of Tyrant to prove it). In addition to singing Lawson's praises, he also offers a very thorough history of dinosaur comics, carefully separating comics with dinosaurs in them (in Lawson's case, that would include his early-nineties two-issue Dino Island and his kickstarted Dragonfly) from true dinosaur comics, featuring dinosaurs in realistic, human-free comics devoted solely to dinosaurs (Sticking with Lawson, Paleo).

And, in the back and labeled as "bonus material," is a short, six-page, wordless story in which two predatory dinosaurs, with the basic features of raptors, only of very small stature, fight. It's beautifully rendered, and much differently than all that proceeded it. It's told in reverse silhouette, with the figures and plant life all solid white, and the black ground all black.

It's a really beautiful piece.

Savanti romero along with a large chunk of characters and ideas from the original comics appeared very prominently in the 2003 4kids tmnt animated series.

ReplyDelete