BOUGHT:

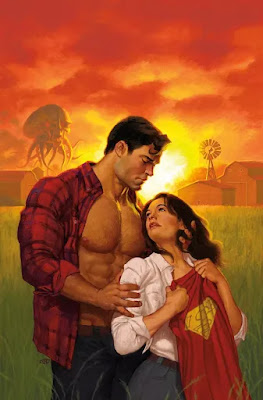

Batman '89 (DC Comics) Imagine there was a third Batman film in the original cycle, one that introduced both Robin and Two-Face. Okay, yes, I know, but not like that; imagine that there was no recasting of Batman or Harvey Dent and, more importantly, that this third Baman film was more strict in its adherence to the first two...or, at the very least, was written by the same guy. That's what DC's Batman '89 is, a sort of comics adaptation to a film that didn't really exist, written by Sam Hamm, who was responsible for writing the original 1989 Batman film and got a story credit for 1992's Batman Returns (this comic, which is set after the events of Returns, is really more like Batman '93, I guess, but they're using the naming rubric established by their Batman '66 comics and carried on in the short-lived Wonder Woman '77 and this book's sister project, Superman '78).

Hamm is joined by artist Joe Quinones, who is about as perfect an artist for such a project as one could wish for, doing a fairly masterful job of modulating celebrity references for the characters who appeared in the previous films so that Batman, for example, looks like Michael Keaton, but not too much like Michael Keaton, to the point where it's distracting, or to the point that he stands out as being more realistically rendered than any of the other characters on the page.

I enjoyed the heck out of this, and it's a great read, particularly for fans of the original film who at least imagined what the potential of the franchise would have been like if Warner Brothers zagged instead of zigged.

That said, it's a thought-provoking comic too, in that I wasn't sure, once I'd finished reading it, how best to evaluate it (I'm glad I didn't have to write a formal review of it anywhere, to be honest). How, really, should one think about it?

Should we approach it as a movie, or, at least, judge it on how movie-like it is? In that respect, it has its weaknesses. Though clearly set in the continuity of the films and featuring the general likenesses of the original film's cast—especially in the case of District Attorney Harvey Dent, who hear resembles Batman's Billy Dee Williams—it doesn't quite read as a movie would play. It's not as visual as it could be, and certainly lacks the action scenes that would have been necessitated by a big-screen outting, with only one real action scene of any length of complexity, and that occurring early in the story.

Should we approach it as a movie, or, at least, judge it on how movie-like it is? In that respect, it has its weaknesses. Though clearly set in the continuity of the films and featuring the general likenesses of the original film's cast—especially in the case of District Attorney Harvey Dent, who hear resembles Batman's Billy Dee Williams—it doesn't quite read as a movie would play. It's not as visual as it could be, and certainly lacks the action scenes that would have been necessitated by a big-screen outting, with only one real action scene of any length of complexity, and that occurring early in the story.

It's also extremely verbal and character-driven...hardly a bad thing, but it reads very much like a movie script rather than a movie. That is, it's not hard to imagine scenes and chunks of scenes that would have been chopped out to make more room for visual story-telling and big, dramatic moments, or even just a change in focus; I've seen enough Batman movies at this point to know, for example, that the introduction of the Bat-cycle would have been given far more play than some of the long conversations in the final product.

So should we approach it as a comic? (Yes, I can hear you say; it is a comic, you idiot. No need for name-calling, imaginary voices in my head). It's a little weak in that regard too. I know Hamm isn't a comics writer—although he has a pretty solid comics story on his resume in the form of "Blind Justice in 1989's Detective Comics #598-600 , which was published in conjunction with the original film's release—and it's obvious from reading this that he's still relatively new to the production of comics.

Remember what I said about how verbal and character-driven this is? It's very talky, and reads like the work of a prose writer whose work has been adapted into a comic rather than a comics writer. The visuals, though masterfully rendered, don't ever take over for the words, and the balance between the verbal and visual seems off in a way that's hard to pinpoint.

(As an aside, I also wondered about how Tim Burton-esque this was; if this is a theoretical third Batman film by Hamm, is it also directed by Tim Burton? It doesn't look like it, Two-Face's Beetlejuice-like striped suit aside; it's not as funny as either Batman film is, nor as over-the-top in its cartoonish visuals, the way Batman Returns was. Comparing Batman to Batman Returns, it is easy to see a trajectory in Burton's visual stylings, and easy to imagine how pronounced they might have been with a theoretical third go-round).

Nevertheless, I enjoyed revisiting this particular version of Batman's world, and especially enjoyed it's extension into the comics. I even enjoyed with wrestling with these ideas of how to approach the book. I definitely wouldn't mind reading more, whether they're presented as epic-length "movies" like this one was, or more traditional comic books simply set in the world of the film (which is what DC did with Batman '66 really, rather than trying to emulate the feel of episodes of the TV show).

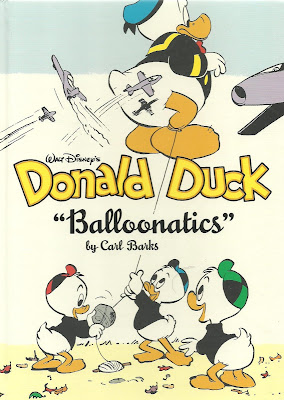

Walt Disney's Donald Duck: Baloonatics (Fantagraphics) I'm trying to catch up on the many volumes of the Complete Carl Barks Library that I missed, and it's not easy; many books seem to be out of stock at the moment.

This later—latest?—volume is notable for it inclusion of Barks-written-and-pencilled, but Daan Jippes-finished Junior Woodchuck stories featuring the nephews and their fellow club-members vs. Uncle Scrooge, who acts as their opponent, always intent on destroying something in the name of progress or profit that the Woodchucks would prefer to preserve (their woodland stomping grounds, a beached whale, a fossil find). The stories are repetitive and, as one of Fantagraphics' panel of Barks experts notes, regressive, casting Scrooge as the unenlightened villain that they do, but even if they're not as strong as the stories that precede them in the volume (and the series), they're still Barks, meaning they're still pretty well-made comics.

As for those preceding stories, they include the title one, in which Gyro's new balloon fuel causes havoc for Donald, the boys' attempts to train a falcon who can't fly and an investigation into sabotaged rocket tests that puts Donald in mortal danger.

BORROWED:

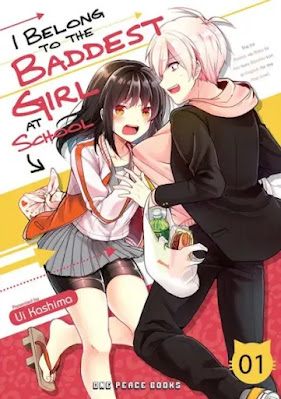

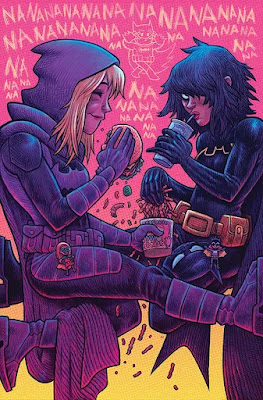

I Belong to the Baddest Girl at School Vol. 1 (One Peace Books) Unoki has been bullied for so long that he's gotten used to troublemakers at school forcing him to follow them and run their errands and so forth. So when his new high school's number one trouble-maker, the hard-fighting, stick-carrying boss Toramu one day pulls him aside and says "Hey, Unoki. Be mine. Well? How about it?", he naturally assumes that she wants him under her thumb, to be her personal property, to bully him, even if she is a girl.

Toramu, on the other hand, thought she was declaring her love, and asking him out.

Thus begins their relationship built on misunderstanding; Unoki thinks she thinks of him as a pliant victim, Toramu thinks they're a couple. Obviously, Unoki can't make sense of certain things, like why she makes him lunch rather than demanding he go buy lunch for her. He only gradually begins to consider the possibility that she might actually like him, and things come to a head at the climax, when a typically manga situation occurs: He falls on top of her.

The moment is broken by a visitor to Unoki's house, in a pretty perfect cliffhanger ending: It's Toramu's older brother, there to collect her.

Mickey Mouse: The Greatest Adventures (Fantagraphics Books) Reading Regis Loisel's Floyd Gottfredson-inspired Mickey Mouse: Zombie Coffee (reviewed in this column) made me want to read more, similar stories of the scrappy, two-fisted Mickey Mouse and his adventures, but I was leery of jumping into the Gottfredson collections, which are of daily newspaper strips, a reading experience I'm not necessarily fond of, and take a degree of dedication I wasn't sure I was ready for.

As it turns out, Fantagraphics has a perfect book for someone in exactly that set of circumstances: Mickey Mouse: The Greatest Adventures offers a smattering of Gottfredson's comics in a single volume.

The collection begins with "Mickey Mouse In Death Valley," a very early story in which a particularly rambunctious Mikey and Minnie are involved in a series of Hollywood-inspired, almost stream-of-consciousness adventures involving a gold mine and the crooks that want to cheat them out of it.

It's followed by later, more tightly-plotted, more sophisticated stories like "Island In the Sky", in which Mickey and Goofy discover the titular island and the world-changing secret that keeps it afloat, "The Gleam," in which Mickey must try to foil a particularly clever hypnotist/jewel thief, "The Atombrella and The Rhyming Man", featuring Mickey's friend Eega Beeva, and "Mickey's Dangerous Double," featuring an evil opposite of Mickey Mouse.

If one wants a place to stat with Gottfredson's masterful Mickey comics, this is it.

Zom 100: Bucket List of the Dead Vols. 6-7 (Viz Media) I somehow fell behind on this series, one of my favorite ongoing manga, but no worries; it just meant I got to read two volumes back-to-back this month.

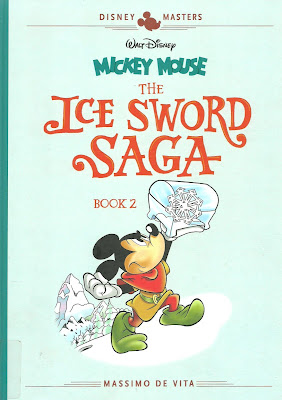

Mickey Mouse: The Ice Sword Saga Book 2 (Fantagraphics) This sequel to the Disney Masters edition focusing on Massimo De Vita's Ice Sword saga includes two more Christmastime adventures of Mickey and Goofy in the fantasy world of Argaar.

In "The Prince of Mists Strikes Back," Pluto is accidentally sent to the dimension of fantasy adventure just as the Prince of Mists, the villain of the original Ice Sword story, seems to have made a comeback. Mickey and Pluto must take an alternate route to arrive there and find the lost dog...and save the world in the process.

And in "Sleeping Beauty in the Stars" the world of Argaar is afflicted with a sleeping spell, and our heroes must journey underground, up a mountain and into space to break it.

The two tales account for about half of the book, so the rest is filled with two non-"Ice Sword" stories. The first of these is "Donald Duck and the Secret of 313," a sort of origin story for his little car that takes a seemingly-odd but grounded in the animated cartoons detour to Mexico, and the latter is "Arizona Goof and the Tiger's Fiery Eye," in which Mickey accompanies Goofy's Indiana Jones-like archaeologist cousin on a treasure hunt.

With De Vita's biography already being told in book one of the series, the backmatter here talks about the Ice Sword saga itself.

Uncle Scrooge: King of the Golden River (Fantagraphics) This Disney Masters volume devoted to the work of Giovan Battista Carpi has a rather unusual and somewhat convoluted Duck tale as its title story.

It begins with both Donald and the boys independently seeking ways to counteract gravity, and leads to the summoning of a Donald lookalike Dondorado, the so-called king of the golden river, who amassed a huge treasure in his ancient Amazon home country, so huge that the riches flowed to him like a river (Despite the title, the story has nothing at all to do with John Ruskin's 19th century fantasy of the same name).

Somewhat coincidentally, Uncle Scrooge has his sights set on the same treasure, and the ducks all decide to team-up to search for it together and split it...despite the fact that greedy Uncle Scrooge and Donald both plan on double-crossing one another, and attempt to do so at nearly every opportunity. The quest is saved from doom by the innocence and good nature of the nephews, as Dondorado stays with them in a variety of magical disguises, using his powers to judge the morals of the questers every step of the way.

The rest of the volume contains two more stories. The first of these is "Mickey The Kid and Six-Shot Goofy," which tells the tale of the Wild West ancestors of our modern day Mickey and Goofy (and, for all intents and purposes, these seem to be the same characters, as if Mickey and Goofy are simply "playing" their own ancestors, like actors cast in new roles). The story also features an appearance by Scrooge McDuck, reminding us just how old the old miser really is. It's the first of what would be a series featuring these versions of the characters, some told by Carpi and some told by other cartoonists.

Finally, there's the weird and not at all legally sound "Me, Myself—and Why?", in which Scrooge decides on a course of action to avoid paying massive taxes: He'll split his vast fortune three ways between three different personalities, each of whom will then only have to pay a third of the taxes. I guess. Being three different people—each with his own hat and name to distinguish him—proves exhausting though, and eventually Donald and the nephews seek out professional help. The advice given by psychiatrist Professor Dingledorf is about as medically sound as Scrooge's scheme seems legally sound, but in keeping with the strip's cartoon roots: A mallet to the head should fix the problem.

The comics are followed by a nice, concise biography of the late Carpi, which emphasizes his importance as one of the two leading lights of Italian Disney comics, alongside Romano Scarpa.

Volume 6 picks up on a cliffhanger in which Akira is put in an impossible position by the evil opposite version of his group: Allow himself to be bitten and become a zombie, or forfeit his father's life. Writer Haro Aso and artist Kotaro Takata have him wriggle out of the circumstances in an interesting way, the cliffhanger/resolution reminding me of something Mark Waid once said during a talk on comics writing about writing cliffhangers so dramatic even you, the writer, don't know how they will be resolved in the following issue.

I suppose it's no surprise to reveal Akira, the hero of the series, survives though, and, as idyllic as his hometown village has become, even taking into account the zombie infiltration and the machinations of the bad guys, he and his friends can't just stay there and settle down. If they did, we wouldn't have a series. Or, at least, not much of one, as it would be more about farming life than traveling through a post-apocalyptic, zombie-filled Japan.

And so they decide to leave, adding an item on their to-do list, the bucket list of things to do before dying or becoming zombies themselves that gives the series its name: Find a cure for the plague.

Volume 7 finds Akira and friends back on the road, searching for a cure—which looks a lot like sight-seeing—before the story takes a weird and interesting detour, wherein they find a luxury hotel completely operated by still-functioning robots that cater to their every whim. Is it too good to be true...? Yes, yes it is. But it's pretty good for a while, and the sequence ends with a zombie bear, the coolest zombie monster faced since the zombie shark in volume 2.

Volume 7 also includes a 12-page crossover between Zom 100 and Alice in Borderland entitled "Akira in Borderland", which is no doubt a bit more exciting for readers of both series, as opposed to just Zom 100. Still, it does a neat job of displaying Akira's core, comedic motivation: He hated his soul-crushing job so very much that anything, even the end of the world via zombie apocalypse, is a welcome respite. Borderland's building full of deadly traps? No sweat! Beats working!

REVIEWED:

Big Ethel Energy Vol. 1 (Archie Comics) Artist Siobhan Keenan's ability to draw attractive young people seems to work against a core conceit of her collaboration with writer Keryl Brown Ahmed: That Ethel Muggs, the "Big Ethel" of classic Archie Comics, was an ugly duckling who bloomed into a beautiful swan after graduating high school and moving away from Riverdale. She's still awfully swan-like in high school flashbacks, not only looking nothing like her classic cartoonish counterpart, but also not looking all that different than she does as a grown-up, when the dialogue tells us she's suddenly a stunner.

That nitpick aside, I was caught up in the story and its several mysteries—like, for example, what's up with Jughead, exactly—pretty quickly, and eager to find out what happens next. The comic plays an awful lot like a young adult TV drama, but of a more gentle, melodramatic variety than the more bonkers Riverdale show. The stars of the comics are all present—Archie, Betty, Veronica, Reggie, Moose, even Mr. Weatherbee and Mrs. Grundy—but now we're seeing them as grown-ups, and from an outsider's point-of-view. It's a well-made comic, and one that should be appealing to readers regardless of their foreknowledge of or experience with Archie Comics. I reviewed it here.

Revenge of the Librarians (Drawn & Quarterly) If one way to judge a cartoon or comic book collection is how often one encounters a strip that one feels compelled to show a loved one—cutting it out of the newspaper, for example, or now simply forwarding it—than Tom Gauld's latest collection of literary-themed cartoons is as successful as can be. Tackling books and their writers, almost every strip is a delight, and one that screams to be shared with one's writer friend or book-obsessed relative. As a guy who works in a library and writes when I am not there, this could hardly be more up my alley. Highly recommended for anyone who likes books.