Earlier this month I wrote a review of writer Kyo Maclear and artist Byron Eggenschwiler's excellent graphic novel, Operatic. Much of the subject matter of their book revolved around music, which is part of what makes it such a remarkable book. Sound of any kind being incredibly difficult to capture in a comic, it therefore almost always stands out when someone finds a new or effective way to do so. Think Doug Moench, and his ability to come up with perfect onomatopoeia for his kung fu-filled super-comics that borders on synesthetic Foley work. Or James Stokoe's now-famous Godzilla roar in Godzilla: Half-Century War. Or Russell Dauterman's use of size and shape of sound effects in his art on Thor comics to imply a sense of scale to them.

In Operatic, illustrator-turned-comics artist Eggenschwiler repeatedly comes up with new and interesting ways to draw sound, music and its impact on its listeners. I talked at some length about all of this in my review, but I wanted to return to the subject here on my blog, where I could better share examples.

If you haven't read Operatic—and I really think you should—it's the story of middle schooler Charlie and where her life is at when her time in middle school is officially coming to an end. She and her friends are in a music class taught by the charismatic Mr. K. He believes that somewhere in the universe, there is one perfect song for each and every individual, and he gives his students an assignment based on that principle. He wants them all to look for their song, and, when they find it, write about it, integrating research on its performer.

But how will they know a song is their song?

"You might not know it's the song the first time you hear it. It might creep on you. But eventually it should make you feel like it was made for you. It should feel like home.

Mr. K.'s song is A-ha's "Take On Me," which is, of course, a great song, even if his students don't necessarily see it as such.

I kind of love the bit where they ask him what the F the words of the title even mean, and he responds thusly:

Mr. K grew up, Charlie narrates to us, "like, a million years ago, in the 1980s." When talking about Mr. K's song, Charlie calls it "The one where the singer starts really low but ends up singing so high you can practically hear the top of his head flipping open." That description is...apt. (In the panel above, by the way, you can see one of Eggenschwiler's sound effects; the sharp, straight yellow lines emanating from Mr. K's snapping fingers. Obviously, he's snapping his fingers, and I don't know about you, but I can hear them snapping by looking at the image.)

Later, Mr. K talks about how when he is listening to the song, it takes him back, and while this is a bit more effective with the two pages side-by-side as a spread, as they are in the book, check out how the creators handle the sequence:

The "present" narrative of Operatic is rendered primarily in yellow (a flashback is drawn in blue, while the events of Marie Callas' life are drawn in red), and here we watch as the "real" Mr. K is broken down into his component parts of black and yellow, gradually transforming into less and less distinct versions of himself, until he is music, or perhaps just the feelings of that music, the yellow swooping line and the black music notes and "DOO DOO DOO" being the same stuff he himself is made of. Note how, in the next two panels, the yellow line of the music encircles and frames specific happy memories from those years, and then gradually re-forms into the real Mr. K at the end.

That's an all-around beautiful sequence, perfectly illustrating the way in which music can take one back and unlock particular memories.

Less importantly, but still amusing to me, is the way the sound of "Take On Me" is approximated with the "words" in that second panel, which, if you've heard the song as often as I have (and/or are playing it on YouTube right now as you read this), you can actually see in the "DOO DOO DUH DOO DOO DOO" on the page.

I'm also not sure if this was intentional or not, but if you have seen the video—which I've seen a million times or so, given that I was just starting elementary school around the time MTV was invented and that was one of the more compelling videos of its era—you know that it is set partially in a comic book, which is drawn in an extremely sketchy, all pencil, no ink style that Eggenschwiler's Operatic actually rather closely resembles.

Here, for example, are two frames of it:

Another song that Mr. K's class talks about at some length is Patti Smith's "Gloria," a song I wasn't quite as familiar with, owing perhaps due to it being released in 1975, a few years before I was even born, and the fact that it didn't have an animated video in heavy rotation in the first years of MTV (Now, Laura Branigan's 1982 "Gloria," on the other hand...).

Anyway, Mr. K and the students talk at some length about Smith, and his more cynical students respond with, "I don't get it, sir. She can't really sing" and "Yeah. She sounds kind of demented. I mean, you know, off."

Here's how Mr. K introduces the song to them, though, and how Eggenschwiler draws it:

The music is still just lines, in the basic colors of the comic—black, yellow and white—but they are more jagged, more unruly and less elegant and formed than the pop music of A-ha, or even the simple sound of Mr. K snapping his fingers.

Patti Smith is a pretty important part of the book, which opens with a quote from her: "When I was a teenager, I dreamed of being an opera singer like Maria Callas."

Charlie, Operatic's teenage protagonist, dreams of being Maria Callas...maybe not being an opera singer like her, but of making her own music, and of being the sort of a person as well as artist that Callas was. In Callas, Charlie finds her song, and here, too, Eggenschwiler comes up with an interesting way of portraying that music sneaking up on and grabbing Charlie:

The very next image is too big to fit on my scanner bed, but it is a two-page spread in which there is no background, just the off-white color of the page. In the foreground, Charlie's desk has toppled, her chair is tangled in the ornate vine of Callas' song, and she herself has all but disappeared. She retains her shape, but it is just outline, filled defined by hr tennis shoes, hair, three lines for her closed eyes and smile, and the music that has enveloped her, which blooms red flowers, red, again, being the sound of Callas.

The next panel following that, we see Charlie's classmates reacting, their words trying and failing to cut through the song—"Una Voce Poco Fa" by Callas—in dialogue balloons shaped like the tools one might use to attack a vine.

Here's an image of a young Callas learning to sing, summoning a butterfly shape.

Later there's a two-page spread of her singing, and the butterfly-shape of her song is huge, bigger than her, fluttering around a packed opera house, coming out of her mouth like fire from a dragon, its flight path described by vaguely ribbon-candy shaped hills and valleys of red and black lines.

It too was too big for my scanner, but I found an image of it online to filch:

There's...a lot of sound in the book.

For example:

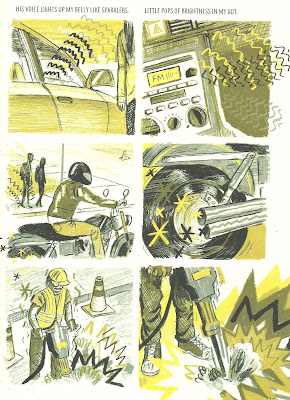

Or:

And on and on. Much of the other images of sound are relatively minor, like the repetitive bold zig-zags of the thick black lines of a blaring car stereo, or the motion lines/sounds of Charlie's friends singing and dancing to Iggy Azalea's "Mo Bounce", or sketchy, lightning-like yellows arcing around a hair metal guitarist, or even the dialogue bubbles piled upon one another in a neat little two-dimensional stack when the whole class says "Yes, Mr. K" in unison.

The more—and more closely—I look at the art in this book, the more I find to admire in its creation.

***************************

On a similar note, but in an entirely different comic book, I really liked the way in which singing and music is drawn in the pages of George Takei, Justin Eisinger, Steven Scott and Harmony Becker's The Called Us Enemy, which is another rather excellent graphic novel you should also seek out and take some time to read. (I wrote a review of that one too, but I can't link to it, as it hasn't yet been published. Hopefully it will see the light of day soon-ish.)

There are two pages in which young George and his family are around Christmas music, the first time while they are free, the second time during a Christmas event in their internment camp:

Sorry for the poor quality of this one; I couldn't get the page to rest on the scanner bed, as it comes much later in the book:

Artist Becker—there's no letterer credited, so I assumed she handled that as well—draws the lyrics of the music directly into the panels, and in cursive, which serves to differentiate it from the more common form of communication seen throughout the book. You know, talking.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment