How is it that Batman, the dread creature of the night who has devoted himself to waging a one-man war against all crime, came to eventually have teenage sidekicks like Robin and Batgirl, and even a canine partner in the form of Ace, the Bathound? That's the mystery that writer Ivan Cohen and artist Dario Brizuela solve in the first issue of the new

The answer involves time travel, undertaken via the Silver Age Batman method of visiting Dr. Carl Nichols. In "Glove Story", Scooby and the gang are visiting the Gotham City Museum of Culture, where there's a big Batman exhibit. But someone seems to have stolen something from among the trophies the Dark Knight lent the museum; specifically, the purple gloves on his first appearance costume are brand-new fakes, apparently replacing the originals, which must have been stolen.

What happened? Well, as with all things time-travel, it's complicated, but to figure it out, Velma, Shaggy and Scooby travel back in time to the era when Batman was still wearing his original purple-gloved costume.

They start their investigation at Wayne Manor, where the Alfred of years ago informs them, "I truly regret that my employer has no use for teenaged associates nor a dog." That's before First Appearance Batman and "Year One" Bruce Wayne encounter the kids and Scooby though, and their inspiration is underlined in a later panel.

Interestingly, Cohen and Brizuela manage to pack elements of various eras of Batman into a single story, with the First Appearance/"Year One" Batman and a modern Batman sharing panel-time with the Scooby characters, and even elements of the Silver Age Batman comics appearing.

There's a panel near the beginning where we get a glimpse of the Batman display at the museum, and there's a line of mannequins wearing various Batman costumes from over the decades, including the Rainbow Batman costume, the Elseworlds pirate costume and even the New 52 costume, and the entire story basically reflects that panel.

Here's a light-hearted Scooby-Doo crossover that takes interesting bits from the whole history of Batman comics,then. The only bad thing? This is just a limited series.

Batman Black & White #4 (DC) This is the second issue of the current volume of

Batman Black & White that I've purchased, even though I know I really should just wait for the trade. The first issue I bought was because I didn't want to have to wait to see Sophie Campbell's take on Batman. This one I bought because it featured a Karl Kerschl story in which Maps Mizoguchi from the late, great

Gotham Academy appeared as Robin..

Interestingly, that story, "Davenport House," isn't really about Maps or centered around the idea of Maps as Robin; she's basically just a Robin, and the story would be little changed were Kerschl to have written and drawn any of the other half-dozen or so potential Robins into it. She's basically there for the same reason Robin is almost always there: To give Batman someone to talk to.

It's essentially just a very clever ghost story with a mystery element, one that allows Kerschl to play up the idea of Batman as the "spirit of Gotham," as others have done in the past. All in all, not bad for eight pages...and it was a delight to see Maps again. It would be great if Kerschl and company could find a way to temporarily revive the Gotham Academy characters; there are so many teens in Batman's stable of sidekicks that it doesn't seem like it would be that hard to do so, and make it marketable enough to appeal to Batman fandom at large for the space of a miniseries or original graphic novel or so...

There are four other stories included in this issue, none of which really take advantage of the black and white format to do anything special or tie-in to it in some notable way, although it is interesting to see what Nick Bradshaw's hyper-detailed art looks like sans color, for example, or what Riley Rossmo's art look likes in black and white (Rossmo, as I am sure I've noted before, is one of my favorite current Batman artists).

The best of the lot is probably Daniel Warren Johnson's "Checkmate," a nice, evergreen, "portrait" sort of story about Batman's relationship with Alfred, how he learned to think ahead and how doing so leads to his peculiar crime-fighting strategies, which can include something as counterintuitve as letting a low-level thug beat on him for a while until his prey comes along. Two-Face is in that story.

As for the rest, they are Joshua Williamson and Rossmo's "A Night in the Life of a Bat in Gotham" (featuring a nice appearance by the Batman family on the final splash page), Chip Zdarsky and Bradshaw's "The Green Deal" (most notable for Batman's intimation that he might already have his own plan to save the world from the climate crisis and environmental degradation, so it's too bad he's not real!), and Becky Cloonan, Terry Dodson and Rachel Dodson's "The Fool's Journey," in which Batman investigates a murder at Haly's Circus, back when Dick was still young enough to be using a pacifier.

All in all, there's a lot of great art, and enough quality comics to justify the hefty $5.99 price tag.

History of The Marvel Universe (Marvel Entertainment) What a strange book this massive, 8.75-inch-by-13.25-inch treasury edition collection of the six-issue miniseries turned out to be. It's honestly probably the most brilliantly-drawn, most brilliantly-written but most boring to read comic I've ever read.

One can't fault writer Mark Waid or artist Javier Rodriguez for the fact that it is a slog to read. It is, after all, the entire history of the Marvel Universe, from its creation—meaning its version of the Big Bang, not Fantastic Four #1—to fragmented, indefinite visions of various alternate futures, told in chronological order. It's one big summary of thousands upon thousands of individual comics, and while it's all boiled down and reconstructed into what may be the most complete, most narratively sound story possible, reading it is still the reading of a summary of the Marvel's publishing history in general (The Human Torch, Namor and Captain America don't show up until the second issue; the Fantastic Four don't get their powers until the third issue, so there's a lot of retroactive continuity in the book).

Waid creates a sort of framing device, with a bearded, grown-up Franklin Richards talking to a dying Galactus at the end of the universe, the latter telling the former the history of everything as a way to remind him of what they are in the process of losing. Each issue ends with something of a cliffhanger, or at least a bit of story with a degree of suspense to it (Like, for example, Galactus narrating that "The stage was set for the Age of Heroes" in the last panel of issue #2, as the future FF run to board their fateful rocket, but how much suspense is there really, when the reader will be well aware of what happens next with every such "cliffhanger"...?).

The real pleasure then is taken from one of two sources. The first, and more vague pleasure, comes from seeing the mechanics of what Waid is doing, how he chooses to boil various bits of Marvel history down into a sentence or panel or two, or entire eras into a page. The other, and more immediate, is in Rodriguez's art, and how he constructs his images, sometimes smooshing whole eras into a single image on a single page, or how complicated story arcs or runs or events might be reduced to compelling imagery.

Of greatest note, I think are these examples, which I'd share if I could fit the giant book onto my scanner: A swathe of seventies debuts filling a single page (Iron Fist, Shang-Chi, Power Man Luke Cage, Werewolf By Night Jack Russell, Man-Thing, Howard The Duck (still forced to wear pants, despite Disney's ownership of Marvel) and Morbius, the Living Vampire; Spider-Man's "Clone Saga" and the attendant era of Spidey comics all drawn in a single striking image; and a page in which The Sentry, Jessica Jones, The Runaways and X-Force/The X-Statix all debut in a single image of at a New York City newsstand.

There's just remarkable imagery throughout, and as striking as it is to see, it's also striking to see how Rodriguez and Waid use it to tell the story of, say, Grant Morrison's New X-Men run or House of M or Civil War in a single image and a couple of sentences of summary. I would love to see some pages of script from this series, just to see if or how the pair worked together to construct the individual images, if it was pure "Marvel method" or if Waid would type out a summery of, say, the Winter Soldier storyline from Captain America and the "Planet Hulk" storyline and then "do whatever you want to summarize them visually" or what, exactly.

The most noteworthy addition the series makes to the Marvel Universe is Waid's invention of an international war in "the Asian nation of Siancong" to take the place of the Vietnam war, giving James Rhodes, Frank Castle, Ben Grimm and Reed Richards all a fake Vietnam war to serve in without marrying them to a historical event, and thus aging them to the point where they would all be senior citizens rather than the eternal thirtysomethings that super-comics heroes are mostly meant to be.

I suppose I should note that I've actually only read the first half of the book. The second half collects the annotations, which are essentially Marvel saga entries, illustrated prose explanations of the events Waid and Rodriguez refer to (with references to the issues the events are from, although these days references to the trades those comics are collected in might be much more useful). I only flipped through that portion of the book. It is obviously far more unreadable as a story than the more comics-like illustrated splash pages that preceded it, but it's a pretty nice thing to have access to on my bookshelf, should I ever want to read about the Celestials or Eternals or the Brotherhood of the Shield or some X-Men crossover without having to consult the Internet.

All in all, a pretty weird book: A beautifully-illustrated reference book of the entirety of Marvel continuity, told about as well as it could be told in so short a page-count. No fun to read, but a true pleasure to look at and even occasionally marvel at (Yeah, I said it!).

I admit I was bummed that Galactus didn't mention the debuts of the Son of Satan or Squirrel Girl, though...

H.P. Lovecraft's The Hound and Other Stories (Dark Horse) Wondering aloud about how film and comics adaptations of H.P. Lovecraft's writing tend to be disappointing

last month got me curious about whether his work would fare better if adapted into Japanese comics, where there's a greater emphasis on imagery-as-storytelling over narration than in Western comics (and no producers or film executives to suggest updating the time period of the setting to the 1980s or 1990s or whatever).

That got me on Amazon, and, eventually, put manga-ka Gou Tanabe's H.P. Lovecraft's The Hound and Other Stories in my hands. Based on this small sample of exactly one (1) work, I can overconfidently pronounce that manga does indeed better capture Lovecraft's work than traditional Western comics like Dave Shephard's recent H.P. Lovecraft's Call of Cthulhu and Dagon: A Graphic Novel.

Aside from the title story "The Hound," the book also collects "The Temple" and "The Nameless City." All are relatively minor works of Lovecraft's (I don't recall reading any of the originals at the moment, but it was a good 25 years ago that I went through my Lovecraft phase), and all tie into the mythos, but in roundabout ways, alluding to and teasing prehistoric, pre-human civilization and horror from a past world lurking on the edges of this world, as if looking for chances to break through.

Of the three, only "Nameless City" really puts "the wonder" or "the horror" on the page, as an archaeologist sees a swarm of monsters flooding into our reality. "The Hound" features a title monster that appears repeatedly, but often in shadow or from afar or just off-panel; it's a pretty great example of showing a monster without completely defining it on the page, and seems to pull off the comics equivalent of what Lovecraft does in his prose as well as possible.

Tanabe's seems to be the best direct adaptation of any of Lovecraft's stories I've read in comic, but then, direct adaptations are relatively rare in the medium compared to stories inspired by Lovecraft.

BORROWED:

Goblin Slayer Vol. 9 (Yen Press) More goblins are slain, this time in the snowy mountains, as Goblin Slayer leads his adventure party in search of a noble whose own party went missing while attempting to lay siege to a goblin lair and starve them out. Something went wrong with that plan, and as our heroes venture into said lair, they begin to suspect that there's something different about these goblins, but all we get in this volume are hints.

There's a hot springs scene, so the attempts at titillating nudity (or, here, near nudity) are thankfully mostly decoupled from sexual goblin-on-human violence for once. We also learn a new tidbit about the lizard man necromancer, as apparently his people can eventually ascend to become actual dragons.

Despite my somewhat flippant first sentence up there, I still find the book engaging, and am still in a state of active suspense regarding many aspects of the narrative, from elements of the protagonist's origin story to the origin of the goblins themselves. And, or course, what creators Kousuke Kurose and Kumo Kagyu ultimately have in store for the relationship between goblin and slayer.

The Girl With The Sanpaku Eyes Vol. 1 (Denpa) It took a bit of Internet research and a consultation with my Japanese friend before I quite got the meaning of the title and how, precisely, it relates to the story, but suffice it to say that it is a very Japanese/Chinese title, and might actually have benefited from a more Western-friendly retitling, like

The Girl With the Psycho Eyes or

Crazy Eyes or

Intense Look or something ("Sanpaku" literally refers to how much of the whites of one's eyes are seen, and in Eastern "face-reading" traditions, different amounts of white in different places mean different things; contextually, it would seem that the girl of the title has the eyes of psychopath or otherwise mentally imbalanced person).

The plot is pretty straightforward. High schooler Amane Mizuno, we are told, "is a girl who has a hard time showing her feelings" and "has a hard and prickly outside, but is soft and pure inside." She has a crush on the boy who sits next to her in homeroom, Katou, but when she looks at him, or when he tries to talk to her, or in the rare instances where she tries to initiate conversation with him, her eyes aren't all big and sparkly and dewy like those of the typical manga romantic heroine; instead she looks angry or intense, her tiny pupils drawn by manga-ka Shunsuke Sorato to almost resemble a serpent's eyes in some instances (as on the cover).

What follows then are her struggles to talk to Katou and be friendly to him, as she secretly "SQUEEE!"s on the inside while looking pissed off on the outside.

The title might be something of a head-scratcher for big, dumb Westerners like me, but the central conflict is kind of fun and engaging, and there's a meta-element to it that makes it work far better in this particular media than it might in any other, as Sorato can use comics shorthand to so clearly delinieate the gulf between Amane's eyes and the way the actually feels. Hers is one case in which the eyes are definitely not the windows to the soul.

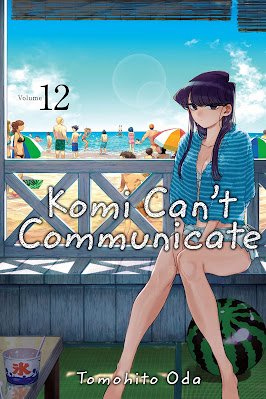

Komi Can't Communicate Vol. 12 (Viz Media) This is

still my favorite current manga series, and one of the comics I most eagerly await new volumes of. In this batch of Tomohito Oda's stories featuring a classful of students who almost all seem to have some difficulty in communicating with one another, (with many of those problems comedic or highly exaggerated), we meet a teacher with a communication disorder; the kids try and fail to stay quiet while studying in the library; there's a girl-boy outting to the beach

without the outgoing Najimi, who usually organizes such events and keeps conversations going; there's a flashback to a beach date that Komi's parents once took; and Komi's household gets an unexpected guest when the young daughter of one of her mom's friends stays over. As always, it's a joy to laugh at Komi and friends, in large part because their disorders are all so familiar, that the laughing

at is really laughing

with.

Zom 100: Bucket List of The Dead Vol. 1 (Viz) Well this is an exceedingly clever, awfully fun high-concept zombie apocalypse comic. Akira Tendo's first job out of college turns out to be an extremely-demanding, high-pressure, soul-crushing one, and he finds himself wishing he were dead rather than pulling all-nighters at work, his only life outside of the office seemingly being occasionally going home to sleep, or to restaurants for dinner with his co-workers between marathon stints at work. It gets to the point that when he sees a speeding train, he thinks of how if it would only hit him, he wouldn't need to go back to work ever again.

So when he wakes up one morning to find zombies in his apartment building and a plane falling from the sky, the end of the world obviously nigh in the now-familiar method of so many films and comics, his reaction isn't horror, but relief: "I'm... ...FREE!!" he shouts to the world, pumping his fists into the air.

The end of the world provides a new beginning for Akira, who is only too happy—in fact, way too happy—about the current state of affair, which give him the chance to do all the things he couldn't do when he was an office zombie himself. He immediately sets about making a to-do list of sorts, things he wants to accomplish before he himself is killed by a zombie, which is where the title comes from. He then starts to implement it, confessing his feelings to the girl at the office he had a crush on (which doesn't go that well, given that she's been zombified), cleaning his apartment, spending a day at home doing nothing but drinking beer, catching up with an old friend.

The cultural criticism at the center of writer Haro Aso and artist Kotaro Takata's comic is a familiar one in zombie literature, perhaps most effectively and explicitly stated in 2004's Shaun of The Dead, but more subtly explored in other works at least as far back as 1978's Dawn of The Dead; that is, that the line between modern life and the shambling, unthinking, unfeeling existence of the undead isn't as bright and as sharp as we might like. Sometimes it takes being confronted with actual, literal zombies to shake us out of our own zombie-like lives.

That's what happens to Akira here, and it was particularly interesting reading this work a year or so into the coronavirus pandemic, as Akira's time spent stuck free of work, mostly stuck in his apartment, unable to go to the grocery store or to visit a friend without risking his life felt more close and compelling than it would have otherwise. Of all the comics I've read in the past year, this is the one that seems to encapsulate the pandemic the most effectively, although one imagines that is more a question of coincidence and timing than anything else.

REVIEWED:

Dear DC Super-Villains (DC Comics) Michael Northrop and Gustavo Duarte's sequel to their 2019

Dear Justice League is exactly what it sounds like.

This time, little kids send fan letters (or, in some cases, "fan" letters) to various villains, all of whom, in this particular outting, belong to a pretty unusual version of The Legion of Doom (That's right, Catwoman, Harley Quinn and even Katana are all on the Legion of Doom in this book).

It's particularly joke-heavy, and a hell of a lot of fun...far more so than

Dear Justice League, I think, in large part because it's a little easier to diss villains than it is heroes, and rather than a generic invading alien army as the opponents our protagonists face, the Legion is ultimately up against the League itself in the final chapter of the book.

I love the way Duarte draws everyone.

My Little Pony/Transformers: Friendship in Disguise (IDW Publishing)

This is quite easily the very best comics crossover since Tom Scioli's

Transformers Vs. G. I. Joe (which, oddly enough, presaged this very story in its conclusion). A certain amount of mileage comes from the sheer weirdness of the pairing, but it's worth noting the book doesn't coast on weirdness alone, and the various contributing writers find connections between the two franchises to make for interesting character pairings and contrasts between the full-cast book-ending segments. For what it's worth, I have almost no My Little Pony experience—unless you count 1986's

My Little Pony: The Movie—but I had not problem following this comic or getting all of the jokes, so it certainly seems new-reader friendly.

The Wolf In Underpants At Full Speed (Graphic Universe) With

this latest installment, Wilfrid Lupano and Mayana Itoiz's

Wolf In Underpants graphic novels are now officially a trilogy. I enjoy the heck of out Itoiz's art in these things, and the weird elements of the forest's society that the books seem to zero in on, like the original's fear-based economy or the second book's treatment of the poor.

EVERYTHING ELSE:

Fully vaccinated, I returned to the movie theater for the first time since

Birds of Prey to see

Godzilla Vs. Kong, a movie that seemed to demand being seen on a big screen. It very much wasn't the Godzilla Vs. King Kong movie I most would have most liked to see (that is, one in which some version of the 1933 Kong battled some version of the 1954 Godzilla), nor is it the Godzilla Vs. King Kong movie

I would have made, but it was a good enough film (Remember, the original 1962

King Kong Vs. Godzilla was terrible, and, if judged as a remake of that movie, then this is a definite improvement).

There was an extremely obvious twist involved (at least if you've watched enough Japanese Godzilla movies), but it nevertheless delighted me when it was actualized, and there was some unexpected nonsense regarding civilization among the Kongs that was at once dumb and awesome.

I was genuinely surprised that a definitive victor in the rivalry was shown, and that it was the one who, on paper, seems like he would be the victor. I don't think we needed two sub-plots involving humans running around beneath the feet of the "titans", and this seemed in large part to be the reason that Godzilla seems more like a guest-star in the movie than one of its title characters, but then, this is perhaps necessary to tie-up all the loose ends regarding titanology, where the monsters come from and where they can go when they're not fighting one another.

All in all it was a fairly solid B-movie, I suppose; disappointing (as I would likely find most such films regarding characters I have so many thoughts and opinions about to be) but not necessarily an awful film. If this is the final of the "Monsterverse" movies, though, it did seem somewhat small compared Godzilla: King of The Monsters, which featured a four-monster battle at the climax, and cameos by a half-dozen other titans. Hopefully the studio has got at least one more movie in them, a Destroy All Monsters-style monster rally movie where we can see all the surviving titans and maybe some new, Americanized versions of the less-popular Toho kaiju that didn't appear in the first four films.

Author Pete Beatty fictionalized the 19th "bridge war" between Cleveland and its one-time cross-river rival Ohio City in his brilliant novel Cuyahoga (Scribner; 2020), creating a Davy Crockett-esque "spirit of the age" in the form of Big Son, an out-sized, tall tale-starring hero who nevertheless exists in something close to the real world, with a real family and real concerns (the book is told in the incredibly colorful voice of his younger, completely human brother, Medium "Meed" Son). Giving Cleveland its own answer to Paul Bunyan obviously makes the book of particular interest to those of you who share a region with me personally, but the book is a blast to read, and should be of particular interest to anyone with a particular interest in the concept of heroes, which, if you're reading this blog, probably means you. I interviewed Beatty about the book for Toledo City Paper, if you'd like to read a little more about it.

Speaking of local heroes, I finally got around to reading Tom Feran and R.D. Heldenfel's Ghoulardi: Inside Cleveland TV's Wildest Ride (Gray & Company; 1997), the only extant biography of Ernie Anderson, who co-created and played the horror host-turned-phenomenon from 1963-1966 during the Golden Age of local television. I grew up with only the dimmest awareness of the character from the sign in my late grandfather's garage from the long-defunct Ashtabula Manner's drive-in restaurant, featuring the diabolical, goateed image of Anderson in character and the words "I drank a Big Ghoulardi" (a colored milkshake, the precise nature of which I can't find anything about on the Internet). Well, that and residual, regional memories of some of his catchphrases. Feran and Heldenfel's book gave me a far greater appreciation, as they concentrate on Anderson's career and public life, particular his rise to local fame and then sudden departure from the Midwest for Hollywood, where he continued his successful other career, in voice work. There's almost no real coverage of Anderson's personal life, aside from a few remembrances from friends and colleagues, so I suppose one could accuse the book of being relatively shallow, but it's the best one we've got so far, and maybe the only one we'll ever get.

In Jesus For Farmers and Fishers: Justice For All Those Marginalized by Our Food System (Broadleaf Books; 2021), author Gary Paul Nabhan writes that Jesus sought his disciples among the “fellaheen,” the food-producing peasantry in first century Galilee, the fishermen, subsistence farmers and day-laborers who found themselves marginalized and exploited by the Roman Empire, which goes a long way towards explaining why so many of Jesus' teachings revolved around fishing and farming. Nabhan then re-tells several stories from the gospels and various well-known parables, transforming them, or at least giving them vitality and even slightly different—or at least deeper—meanings, once additional agricultural or fishing context is added and explained. It's not simply a book recontextualizing and explaining certain teachings, however; Nabhahm also draws parallels between the fellaheen of the first century and the low-wage, often exploited food-producers of our own society, and how certain modern farming and fishing methods threaten the land and sea and their ability to remain productive.

Michael E. Mann's The New Climate War (PublicAffairs; 2021) is a particularly pugilistic entry into the ever-growing library of climate crisis literature. A long-time combatant, Mann's time in the trenches has meant he's got plenty of scores to settle and thoughts on climate activism (like, are you doing it wrong, for example) and what he calls "climate inactivism," which outright denialism is morphing into. That, in fact, is the new war he mentions in the title. While the scientific issues are about as settled as science of any kind ever is, the enemy army is moving away from denial and into various tactics to delay change. There's plenty of interesting stuff in here (I was particularly intrigued with the discussion of deflection campaigns past and present), even if it's ultimately probably not your best option for a book on the climate crisis. More on my other blog, which you should visit now and then if you want more frequent Caleb-writing-about-stuff in your Internet-reading diet.

Finally, I listened to the audiobook version of Carlos Lazoda's What Were We Thinking?: A Brief Intellectual History of The Trump Era (Simon & Schuster; 2020). Each chapter is a rather expansive essay from the Pulitzer Prize-winning book critic for The Washington Post devoted to a genre of Trump books, from resistance literature to the so-called "chaos chronicles" about what was going on behind the scenes at the White House, from would-be explanations from what those in the heartland were really thinking to how conservative intellectuals were responding to Trump's ascendancy. In this manner, Lazoda seems to able to review dozens of books at a time, often extracting the most relevant information from them and assembling it in a way that helps contextualize it while finding broader themes.

If the news is the first draft of history, then Lazoda's book reads a bit like the third draft, as he makes sense of the constellation of books about Trump and the last half-decade or so. I found myself actively envious of Lazoda's writing while listening; not necessarily the way he writes, but the way he thinks and is able to assemble such pieces out of reading, say, eight books (or maybe he would read 20 and only mention eight). It's a valuable skill that I marveled at, and wish that I possessed it to apply to books on the environment (as I'm reviewing them, perhaps inefficiently, one-at-a-time on my other blog) or to books about comics, which no one seems to really be covering (but then, it's hard enough finding decent reviews of comics themselves, I suppose reviews of books about comics is asking too much).

No comments:

Post a Comment