That was, of course, the original line-up when the team debuted in 1960, the team consisting of all of the DC Comics characters with their own features at the time (give or take Green Arrow, who would join shortly thereafter). And, with lots of additions and only occasional subtractions, that was the core of the Justice League for almost 25 years.

But by 1997, it had been a long time since all of those characters, which included the most popular as well as the most iconic of the publisher's heroes, were on the League together. The so-called "Satellite Era" came to a close in 1984, at which point the Justice League reformed into what would become known as "the Detroit League", veterans Martian Manhunter, Aquaman, Elongated Man and Zatanna teaming with new heroes Gypsy, Vibe, Vixen and Steel.

That era then gave way to what we now think of as the "JLI Era," beginning with Keith Giffen, J.M. DeMatteis and Kevin Maguire's 1987 Justice League #1. The Giffen/DeMatteis run would include several different teams and several different books, lasting some five years, after which DC would continue publishing multiple Justice League books, and their creators would mostly stick to the pool of characters that Giffen/DeMatteis used, with a few additions.

While Batman, Superman, Wonder Woman, Flash and various Green Lanterns would sometimes join Justice League mainstay Martian Manhunter as members of these various teams, they never all served together, instead usually anchoring a line-up of lesser known characters.

So by the time Grant Morrison must have been pitching the book that became JLA, it had been some 13 years or so since the team even resembled its original all-star line-up, an eternity in comics (which at least used to be geared toward young readers, where the turnover could sometimes be a matter of years, although this was obviously changing by the 1980s, as adult readers gradually began to become the norm, and little kids the exception).

Some of the characters might now look quite different than in the old Super Friends or Super Powers cartoons (like the long-haired, hook-handed Aquaman) and some of them had different secret identities behind their masks (The Flash was by then Wally West, of course, and Kyle Rayner had just become the new Green Lantern a few years previously), but, when Morison's JLA launched, the line-up was once again made up of DC's biggest characters, all of whom anchored their own books at that point, save for Martian Manhunter (although, thanks in large part to the popularity of JLA, he would get his first ongoing series in 1998).

Morrison was paired with pencil artist Howard Porter, who had previously drawn most of DC's characters in 1995's Underworld Unleashed, and whose style was timely without necessarily given to the excesses one might associate with the most popular superhero comics artists of the 1990s.

It worked. Morrison swiftly transitioned from the Justice League as it stood before theey took over to their new conception, within the first issues. Morrison's new villains knocked the previous team's satellite out of the sky and forced them to make an impossible escape, which seemingly killed off Metamorpho (temporarily, of course, as Morrison would acknowledge during the character's funeral scene in an upcoming issue). Superman and the other characters quickly assembled to save the world from these villains...and then they decided to keep saving the world together.

I assume sales data was available at the time, but I didn't pay attention to it back then. I was just 20, a college student who hoped to one day write comics and hadn't yet considered writing about them instead (aside from the many, now embarrassing letters I used to send into the letter columns of the DC comics I read at the time, of course).

The sales must have been quite healthy, though, based on how much JLA product DC would publish. There were, of course, the sorts of associated titles most popular DC Comics got at the time, annuals, Secret Files & Origins specials, 80-Page Giants and even a "gallery," a collection of pin-ups.

But there were also a bunch of JLA-branded one-shot specials and mini-series, a pair of spin-off maxi-series (JLA: Year One and Justice League Elite) and a few original graphic novels (JLA: Earth 2, JLA: Heaven's Ladder, JLA: A League of One).

The team also engaged in a fair amout of inter-company crossovers, seemingly commensurate with those of Superman and Batman: JLA/WildCATS, JLA Versus Predator, JLA/Witchblade, JLA/Cyberforce and, of course, the big one, JLA/Avengers.

Members of the team got their own books, not only the aforementioned Martian Manhunter series, but original character Zauriel starred in a three-issue miniseries, and Plastic Man got a special and an 80-Page Giant before eventually earning his own ongoing series, his first since the 1970s. A new, android version of Hourman, introduced in the pages of Morrison's JLA, also got his own ongoing series.

And eventually, DC added a second JLA monthly, a Legends of the Dark Knight-style anthology series featuring different creative teams on each arc, JLA: Classified.

Not all of these comics were, good, of course, and while I'd like nothing more than to go through them all and give you my opinions on them sometime, my point here is just that there was a lot of JLA comics for a few years there, apparently reflecting the popularity of Morrison's "Big Seven" plus other heroes approach to the team.

I certainly loved it.

Morrison was quite adept at coming up with challenges big enough to threaten such a big, powerful and experienced team, mixing old foes from their then nearly 40-year history with new and original villains. The writer's characterization could be limited to sketching out the relationships between the characters, but then, they all had their own books (or in Superman and Batman's case, whole lines of books) to explore their psychology and personal lives, and, as ever, he left a lot of the story implied and off the page, so that readers could fill-in any blanks with their own imaginations.

Morrison's run managed the neat trick of Silver Age-esque conflicts—lots of big, crazy ideas—filtered into the more realistic (or, this being super-comics, "realistic") aesthetic of comics at the turn of the century, constantly escalating threats (and, remember, the very first story involved saving the world), all while managing to be about something.

Morrison's run, all with artists Porter and Dell and the occasional fill-in artist, lasted through 2000's #41, with eight fill-in issues from other writers (five penned by Mark Waid, a sixth by Waid and Devin Grayson, one by up-and-comer Mark Millar and another by J.M. DeMatteis).

Morrison was followed by Waid, who, in addition to his fill-ins on the title, had also written a sort of prequel miniseries, JLA: Midsummer's Nightmare, and the maxi-series JLA: Year One. After his first story arc, pencilled by Porter, Waid was technically paired with artist Brian Hitch, although outside of their over-sized graphic novel Heaven's Ladder, Hitch was never able to complete a single story arc, needing assists from fill-in artists to keep the book on schedule.

Waid reduced Morrison's League, the ranks of which had swelled to a dozen heroes, to just eight, the founding seven plus Plastic Man. If I recall interviews from the time correctly, this was because Waid wasn't entirely sure which characters would survive Morrison's final arc, "World War III."

His run on the series, which began with 2000's #43 and concluded with 2002's #60 (and had only a single fill-in, a Joker: Last Laugh tie-in by writers Chuck Dixon and Scott Beatty), was more tightly focused on the characters on characterization, particularly the relationships between the characters, with one throughline being the team's decision to finally reveal their secret identities to one another in order to instill a greater degree of trust. Perhaps surprisingly, given Waid's apparent affection for DC Comics past, his run featured as many new threats (the Queen of Fables, the Cathexis and Id) as older ones (Ra's al Ghul, The White Martians).

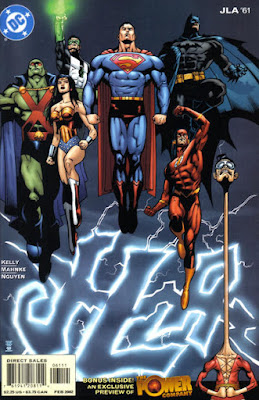

Waid was then followed by writer Joe Kelly, coming off work on the Superman franchise, who was paired with pencil artist Doug Mahnke. Kelly's (consecutive) run ran from 2002's JLA #61 to 2004's #90 (with only a single fill-in, a Rick Veitch-written one in JLA #77). Kelly's run started with the Big Seven plus Plastic Man team, minus Aquaman, who had been temporarily killed off in the 2001 Superman event "Our Worlds At War".

During the "Obsidian Age" arc, in which the team goes back in time, a substitute League is created, featuring Nightwing, Green Arrow Oliver Queen, Jason Blood, Hawkgirl, The Atom, Firestorm, Major Disaster and new, original character Faith and, in the wake of the story, the team would reconfigure a bit, having J'onn J'onnz, Plastic Man and the resurrected Aquaman all take leaves of absence, adding some of those characters from the substitute League plus the ancient shaman Manitou Raven to the line-up, and, finally, substituting Green Lantern John Stewart for Kyle Rayner (At the time, this last change seemed to have been made mainly to make the team resemble that of the cartoon Justice League series, although it did finally add a person of color back to the team line-up; it had been all white people since Steel disappeared somewhere between the Morrison and Waid runs.)

The Big Seven that launched the team was now the Big Five, then, but the book was still oriented around DC's more powerful and popular characters.

In addition to adding new characters to the mix, Kelly managed to continue the book's focus on world-ending threats like Morrison and Waid, but seemed to focus on the characters and their relationships even more than Waid had, like giving Plastic Man a son (a move I detested at the time, as it presented one of my favorite characters as a deadbeat dad, although Plastic Man does eventually decide to dedicate himself to his son during Kelly's run), having J'onn try to overcome his weakness to fire and start a relationship with new-ish Superman villain Scorch and teasing a romantic relationship between Batman and Wonder Woman that they ultimately decide not to pursue (thanks to time spent in a Martian device that shows them possible futures).

Though Kelly's last consecutive issue was #90, he didn't exactly leave the title then. After nine issues of what seemed like fill-ins (a three-issue arc written by Denny O'Neil, a six-part arc written by John Byrne and Chris Claremont), he returned for his final issue, #100...which lead directly to the spin-off series Justice League Elite, which featured Leaguers The Flash, Major Disaster, Manitou Raven and a returning Green Arrow joining a new version of The Elite, an Authority-analogue team that Kelly had written in his well-liked "What's So Funny About Truth, Justice and the American Way?" story in 2001's Action Comics #775 (This new JLE would again feature art by Kelly's JLA teammate Doug Mahnke).

JLA would continue publishing for another 25 issues but coupled with the nine issues of fill-ins by O'Neil and Byrne and Claremont, it was an extremely weird title, having become an anthology series in the mode of Legends of the Dark Knight...or JLA: Classified or JSA: Classified, both of which launched in 2005.

After some seven years and 90 issues of fairly tight issue-to-issue and run-to-run continuity, it was a strange, even perplexing swerve, and while the quality of these arcs varied greatly, they all seemed disconnected from one another, and, in some cases, from the goings-on of the DC Universe at that time in general.

I would love to know what was going on behind the scenes. Some of these stories may have been specifically commissioned for the title—the Byrne/Claremont pairing, for example, was likely seen as a big deal by someone at DC, and maybe the equivalent of a Grant Morrison or Mark Waid among readers of a certain age (and fans of a certain book from a certain other publisher many years previous)—while some of them seemed like they might have been inventory stories, or proposed miniseries or one-shots that were instead folded into the main title.

There's little to distinguish, say, the Chuck Austen/Ron Garney "Pain of the Gods" or Kurt Busiek/Garney "Syndicate Rules" from the pages of JLA from, say, the Gail Simone/Jose Luis Garcia-Lopez "The Hypothetical Woman" or the Dan Slott/Dan Jurgens "The Fourth Parallel" from JLA: Classified.

After a handful of arcs that felt unmoored, JLA finally returned to DCU continuity, its final arcs being tie-ins to other goings on. Geoff Johns and Allan Heinberg wrote the five-part story arc "Crisis of Conscience," in which the modern League contends with the actions of the "Satellite Era" team (some 25 years earlier, our time) that were revealed in Brian Meltzer's ridiculous Identity Crisis miniseries. Dealing with the morality of magically (and/or psychically) altering people's brains to change behavior or keep secrets, it featured various old Leaguers and some of the modern JLA, at least those that the writers thought were around at the time (Firestorm died during Identity Crisis, and The Atom dramatically shrunk himself out of view; one could imagine that maybe Major Disaster and Manitou Dawn decided to stick with some off-page version of The Elite; and Plastic Man...? Well, they seem to have just forgotten about him entirely).

The book ended with Martian Manhunter and John Stewart as the only heroes left on the League...and then the Watchtower being destroyed and J'onn seemingly killed in a cliffhanger ending. (When it was picked up on in the pages of event series Infinite Crisis, Superman, Batman and Wonder Woman gathered to bicker in the ruins of the Watchtower; it would ultimately be revealed that it was Superboy-Prime that had destroyed the base.)

And the final arc, "World Without a Justice League", was a six-issue arc written by Bob Harras, following Green Arrow Oliver Queen as he and a few allies (Manitou Dawn, Aquaman) travel the DC Universe, meet various characters and deal with aspects of the Infinite Crisis plot, while engaging classic Justice League villain The Key.

And that was that, the end of the series.

And the end of the team...at last until 2006, when Brad Meltzer and company would launch Justice League of America, a troubled title with an incredible amount of creative team turnover that nevertheless manage to stick around for 60 issues, when it was cancelled along with the rest of the DC line to make room for The New 52.

I've been thinking a lot about the weird final few years of JLA lately, having fallen down a bit of a rabbit hole trying to answer what I assumed was a simple question recently—When, exactly, was Plastic Man on the Justice League.

While I had read the Morrison, Waid and Kelly issues of JLA (and many of their tie-ins) over and over again in the course of the last few decades (especially the Morrison ones), I had only read issues #91-120 the once...if that (I bailed on the Byrne/Claremont arc after an issue or two; having not read Marvel comics in the 1980s, their names weren't much of a draw to me personally, and I didn't care for their Justice League vs. vampires story that served as a stealth launch of a new soft-rebooted Doom Patrol).

So I thought I might revisit these comics and, of course, write about them here. I wanted to do so in order to maybe more fairly evaluate them, now that I am so far removed from my initial disappointment in their lack of connectivity to the title that they were appearing in, and I'm curious to see how they might hold up some 20-ish years later (If I remember them correctly, some seemed designed to be more-or-less evergreen, while "Crisis of Conscience" and "World Without a Justice League" were obviously closely tied to the events of other old comic books, and thus might not make much sense if encountered for the first time in 2025).

That, then, is going to be the next series on EDILW, seven posts that each examine one of the stories published in JLA after #90, the last consecutive issue of Kelly's run. I plan to post one each Monday, with posts on other comics on Thursdays, in the hopes that none of you get too sick of me talking about 20-year-old JLA comics.

Next: Denny O'Neil and Tan Eng Huat's "Extinction", from the pages of 2004's JLA #91-93

No comments:

Post a Comment