The opportunity to edit and illustrate a selection of Mother Goose rhymes came at a good time for Charles Addams, according to biographer Linda H. Davis’ Charles Addams: A Cartoonist’s Life.

The opportunity to edit and illustrate a selection of Mother Goose rhymes came at a good time for Charles Addams, according to biographer Linda H. Davis’ Charles Addams: A Cartoonist’s Life. By the mid-‘60s the New Yorker cartoonist’s income had dipped significantly due to the cancellation of The Addams Family TV show, and he was always reluctant to try his hand at a different medium than cartooning.

His fellow New Yorker artist Robert Kraus had just founded an imprint for children’s books, however, and wanted to launch with the work of the magazine’s cartoonists, staring with Addams choosing his own nursery rhymes and illustrating them how he saw fit. The Charles Addams Mother Goose was thus published in 1967.

The result? According to Davis, the historical record seems mixed. The New York Times “gave the revered cartoonist a rare snide review,” stating that it was “purely a joke; the gruesomeness is familiar, safe and temporary.” The royalties, Davis said, were scant. Simon and Schuster republished in 2002, and that’s the edition I read. For whatever it’s worth, it was only with some difficulty I found a copy. The library I go to most often didn’t carry it, and the Columbus Metropolitan Library system only has one copy.

I was quite glad when I finally did get my hands on a copy, although it’s difficult to honestly, objectively assess a book like this so many decades after its publication, when a reader approaches it fully aware of the artist’s reputation and influence.

It’s certainly a welcome work, for the opportunity it affords to look at Addams’ art in a new context (i.e. a context other than single image New Yorker cartoons or the occasional painted cover of the same magazine), and yet it’s also a rather awkward work.

The particular nursery rhymes are almost all completely beside the point; they’re all only there to give Addams something to match an image to, and many of these images comment on the rhymes in a way to completely change them.

“Pease porridge hot, Pease porridge cold” is illustrated by an old witch stirring a cauldron of something with a tentacle, a humanoid hand and two eyeballs poking out of it, while two bird-legged little goblins away with long wooden spoons.

“Wee Willie Winkie” becomes some sort of monster, with the cadaverous look of Lon Chaney’s opera phantom, and Nosferatu-esque fangs and ears, dressed in a nightcap and gown knocking on a window like an apparition.

And, for perhaps the best example, here’s Addams’ Humpty Dumpty:

The fact that something hatches from the broken egg man certainly changes the nature of that little nursery rhyme, doesn’t it?

Addams’ efforts to transform, or at least recontextualize the rhymes, is admirable, particularly when he succeeds as well as he does with the Humpty Dumpty illustrations. Less successful are his forced efforts to involve the Addams Family. Wednesday and the mean little boy in the striped shirt we know as Pugsley play the children, Grandma plays Mother Goose herself, as well as a variety of old ladies throughout, and Uncle Fester is give a good half dozen or so roles to play, many of them rather far outside his range.

For example, here he is as the Jack who built the house that Jack built:

The weird family appear as themselves in one full-page black and white illustration, streaming from outside their familiar Victorian manse and into a graveyard just across the street (illustrating the rhyme “Girls and boys, Come out to play, The moon does shine, As bright as day…”), but more often than not they are cast like actors and actresses into different roles, so that Wednesday plays Little Miss Muffet, for example, and Pugsley Pretty John Watts and Tom, Tom, the piper’s son.

And that, above all else, is what makes the book somewhat awkward. Addams doesn’t pick a strategy and stick with it, but offers more or less straight illustration on one page, then an episode of The Addams Family plays Mother Goose on another, then offers a humorous cartoon version of a rhyme (Like the “American Gothic” couple performing “Three Blind Mice”) and then attempts to twist a rhyme into a different narrative.

Based on what’s here to see, any strategy would have worked perfectly well, but vacillating between all four makes for a somewhat frustrating book.

* * * * * * *

The 2002 version contains a six-page “The Charles Addams Mother Goose Scrapbook” including a few photos of Addams from various points in his life, the covers of the various collections of his cartoons, a drawing of a train he did at age four, and an unpublished illustration meant for the book:

The scrapbook includes a few sentences of text beneath this image, saying, “For reasons unknown, this piece was deleted from the book at the last moment.” I can’t tell if that’s mean sarcastically or not. That is a mushroom cloud on the horizon, right? And the shepherd and his sheep are fleeing into a bomb shelter in the face of an atomic bombing? If so, it seems clear why that image might have been cut, although an image of a post-nuclear war landscape did make the cut. (Oddly, in the Davis biography I was referring to, this image is reproduced in black and white, where it loses its menace, and Davis doesn’t seem to read it as a mushroom cloud, referring to the shape on the horizon as “an ominous tomato-red twister mov[ing] in.”)

* * * * * * *

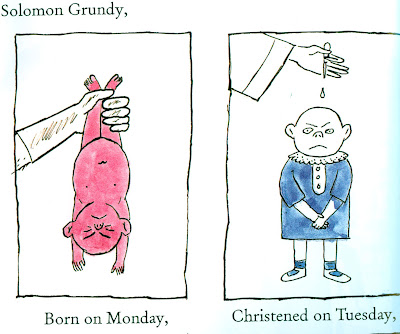

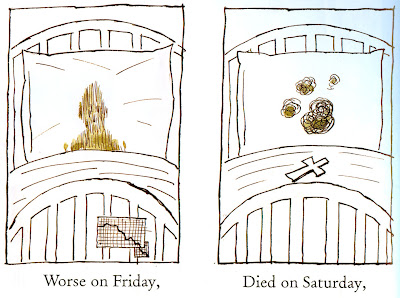

Finally, since we talk about DC Comics super-characters here so often, it wouldn’t seem right to discuss The Charles Addams Mother Goose and not share his two-page, seven-image version of the Solomon Grundy rhyme, chopped up a bit to make scanning of it possible (in the original, Monday through Thursday ran across the top of a two-page spead, and Friday through Sunday beneath them), and, obviously, they don't include the weird shadows that trying to scan the pages without damaging the book resulted in.

I'm not sure exactly what S.G. took ill with, but any disease whose symptoms include mushrooms growing out of your head and climaxes in the disintegration of the afflicted sure is a pretty scary one.

1 comment:

I wonder if The Charles Addams Mother Goose influenced Jasper Fforde's nursey-rhyme themed whodunit The Big Over Easy, which also featured a dinosaur hatching from Humpty Dumpty.

Post a Comment