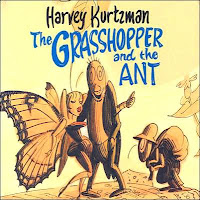

The Grasshopper and The Ant: Harvey Kurtzman’s comics version of the classic insect fable was originally produced in 1960 for Esquire magazine, and almost 50 years later it’s still a remarkably relevant work. Perhaps that should come as nor surprise; 50 years is awfully recent compared to the original fable’s suspected vintage (Heck, the Bible’s Book of Proverbs includes a version of it).

The Grasshopper and The Ant: Harvey Kurtzman’s comics version of the classic insect fable was originally produced in 1960 for Esquire magazine, and almost 50 years later it’s still a remarkably relevant work. Perhaps that should come as nor surprise; 50 years is awfully recent compared to the original fable’s suspected vintage (Heck, the Bible’s Book of Proverbs includes a version of it).Of course, it might also come down to the fact that this is a Kurtzman comic we’re talking about, and the late, great cartoonist’s work boasts a vitality and originality that makes it always seem fresh and new. (When I first encountered his work, it was his covers to the earliest issues of Mad that were reprinted in various price catalogs and histories of comics, and I remember being quite shocked to learn that those drawings were done before my parents were born, but looked just as fresh as last Saturday’s Saturday morning cartoons).

Kurtzman’s The Grasshopper and The Ant is a 37-page story, with each page consisting of a single large drawing, the edges of the page making each page its own de facto panel, with the lovely hand-lettering in dialogue balloons sometimes breaking the single image into several moments, by virtue of the time it takes to read all the words. (We probably shouldn’t get into this now, but Kurtzman does some pretty amazing stuff in these pages when it comes to manipulating time through the interaction of the words and pictures…it’s particularly amazing given the perfect uniformity of the pages and panels; given the format, each page should “last” as long as every other one, but that’s not the case. Shit, this is a comic not just to read, but to study).

You probably know the basic story. There’s a grasshopper and an ant. The former wants to sing and dance and play all year around, while the latter works gathering food; when winter comes along, the grasshopper has nothing to eat and either starves or is saved by the ant so he can survive to learn his lesson.

Kurtzman’s version has a sucker-punch twist befitting the work of a cartoonist—particularly a cartoonist who is also one of the founders of Mad—but it’s the execution and the details that make this an exciting read.

The 1950s origins of the comic are somewhat apparent in some of the details, with the grasshopper making long-winded speeches and playing the bongos while his fellow insect beatniks (bugniks?) read poetry or play jazz, or the insect equivalent: “This is th enew ‘cool-chirping,’ Ant…semi improvisational, distinguished by an immediacy of communication; an expressiveness characteristic of the free use of the voice and forming a complex, flowing rhythm.”

All the ant wants to know, however, is “Can you gather grain to it.”

Kurtzman gets a lot of mileage out of simple bug jokes, like Grasshopper talking to what he thinks is Cicada (but is really just Cicada’s discarded exoskleton), and/or the application of insect details to normal human situations and conversations, like Ant remarking on how a hot, Kurtzman-curvy butterfly was the “freckle-faced caterpillar I sued to know—with pigtails and braces” or individualistic Grasshopper scoffing when someone hints there’s a “big Locust Plague staring up…Big outfit! Security…”

“Me?” he says, “Join a plague? CONFORM?”

Underlying the panel-to-panel gags is the sense that bug-life, even more so than the human life they’re playing at, is extremely short and likely to end suddenly and violently, adding to the tension of a story we all know ends with one of the characters either dying or almost dying.

As I said though, Kurtzman’s version is his own version. As big a fool as his grasshopper may be, he’s still a cool fool, and if never doing any work at all is bad for your health, constantly doing work at the expense of all else isn’t presented in a necessarily healthy light either. This Grasshopper and Ant are two unappealing extremes, so it’s neat to see that they both have something to learn from the other before the final pages, and that Kurtzman has a darkly funny ending in mind all along.

If the moral of the original was something along the lines of “To work today is to eat tomorrow” or “If you don’t work in the spring, summer and autumn, you’re totally going to starve to death in the winter,” Kurtzman’s seems to be something along the lines of, “No matter how hard a worker you are, and no matter how with it and cool you are, if you’re a chump, you’re going to come to a bad end.”

And is there any more important moral to learn and internalize than, “Don’t be a chump?” I think not.

Hawks of Outremer #1: Robert E. Howard’s characters have given birth to thousands of pages of comic books over the years, and yet Marvel, Dark Horse, and other publishers still haven’t managed to exploit them all. Enter Boom Studios, which is adapting Howard’s 1931 short story “Hawks of Outremer” into a four-issue miniseries.

Hawks of Outremer #1: Robert E. Howard’s characters have given birth to thousands of pages of comic books over the years, and yet Marvel, Dark Horse, and other publishers still haven’t managed to exploit them all. Enter Boom Studios, which is adapting Howard’s 1931 short story “Hawks of Outremer” into a four-issue miniseries.The star of the story is Cormac Fitzgeoffery, a typically badass, no-nonsense Howard hero, this one an Irish chieftan who was fighting against Saladin and the “Moslem” during the Crusades. When the story opens, he’s presumed dead, and after recounting his tale to one of the few men he counts as friends, he learns that a man he owed allegiance to has been killed. So he sets out to kill those he holds responsible, both by direct action and self-interested inaction.

The first issue of the series, adapted from Howard’s story by Michael Alan Nelson, is pretty much a perfect serial comic book, in terms of structure. It’s a fairly complete story all on its own, with an introduction to the character and setting followed by a conflict with a beginning, middle and satisfying end, but there’s an overarching conflict to propel a reader into the next issue. In other words, it works as a single 22-page story, and as the first chapter of a longer story.

Nelson does a great job of turning a prose piece into a comics one—this looks and works like a comic book, rather than something adapted from prose, and Nelson relies on the images of the art and the dialogue to tell the story, not resorting to captions or narration.

The art is provided by Damian Couceiro, and it’s pretty strong. His Cormac has the pissed-off, scary look of Conan and Solomon Kane, and is fairly hulking compared to the other characters. Couceiro is given an awful lot of the heavy lifting to do, but bears the weight well, and colorist Juan Manuel Tumbrus makes it look as if pen-and-ink drawings are done over water-colored backgrounds.

It’s somewhat slight—it’s a Robert E. Howard 12th century revenge story, after all, and Howard’s not the most complex writer in the world—but it’s very well done.

Uncle Scrooge #392: This is a Duck Tales-centric issue, which is kind of amusing—a Disney duck comic heavily inspired by an old Disney duck cartoon that was adapted from old Disney duck comics.

Uncle Scrooge #392: This is a Duck Tales-centric issue, which is kind of amusing—a Disney duck comic heavily inspired by an old Disney duck cartoon that was adapted from old Disney duck comics. The issue is broken up into two complete stories by two different creative teams, and they’re both quite solid. This is a comic book anyone of just about any age could pick up and enjoy.

The first is “Everlasting Coal,” written by Paul Halas and Tom Anderson and drawn by Zavier Vives Mateh. This one reminded me the most of the classic Carl Barks-style Uncle Scrooge stories, with the ducks going off to a far off land to exploit a resource, and having an adventure in the process. The resource here is coal that burns indefinitely without ever being consumed, which can only be found in a mountain range ruled over by a bandit named after a type of delicious rice.

The second is “The Littlest Gizmoduck,” which is written by Disney Adventures Staff (that’s a funny name), drawn by artist Robert Santillo and finds Huey, Dewey, Louie and Webby (which doesn’t rhyme at all) constructing their own homemade Gizmoduck costume, and then using it against the Beagle Boys.

I’ve always been more partial to the traveling adventures, so I enjoyed the first story more, despite the more dynamic art Santillo provides the second one. As someone who grew up with Duck Tales (the cartoon) and then discovered Carl Barks’ duck tales (the comics) as an adult, I particularly enjoyed seeing Donald Duck and Donald Duck stand-in Launchpad McQuack together with Uncle Scrooge and the nephews in the first story and, yeah, I admit it—seeing Gizmoduck again did push a nostalgia button I didn’t know I had.

1 comment:

I'm simply amazed to find out they still publish Uncle Scrooge comics in the USA.

Post a Comment