In this tale, a young girl named Quincy encounters Lincoln's ghost in the White House, and they talk: He tells her of his bad dream, he tells her a few funny bad jokes and of his worries regarding the state of the country when he left it, and that he left it before he could solve some of its more intractable problems.

Quincy assures him that the country's not in such bad shape after all, and that while we're still working on some of those problems, we've come a long way, and often seem to be heading in the right direction.

She demonstrates this by taking Lincoln's hand, and having him fly her all around the country.

It's a cute, quite charming story, and Smith's art is amazing. He focuses on the easily exaggerated, cartoon-ready elements of the president to make a rather inspired version: Stick-thin limbs, only a few times thicker than the white stripes on his black sleeves and pant-legs, a mournful, white face top a big head resting wearily atop his neck, a perfectly proportioned stovepipe hat that fits snugly atop his head, and increases his height by another foot or so.

He is in rather spectacular contrast to the Quincy character, a little black girl with who stands about the size of his head, from beard to tophat top, and who wears a yellow, triangular dress. In shape, size and color, she contrasts the late president dramatically.

There's something old and monumental looking about the pages, with age-like cracks appearing behind the artwork, which is full of little lines, like the images on, say, a five-dollar bill. The text—which changes color, size and shape slightly throughout, usually to indicate a change in speaker—similarly looks like that found on money, and/or on/in posters and newspapers from the late 19th century.

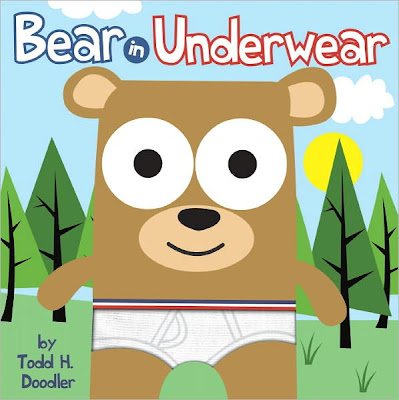

Bear In Underwear (Blue Apple Books; 2010): Todd H. Doodler's 2011 book Bear In Long Underwear was previously discussed in a previous installment of this column, and it was only when I saw this book that I realized it was actually part of a series (There's also a third book, Bear In Pink Underwear and, as it turns out, a whole slew of underwear-related books by the author).

All of the charms of Long Underwear are obviously also present in the original, including Doodler's charmingly square woodland creature designs, his inclusion of a Bigfoot (named "Big Foot") among them and a pretty cool cover design in which Bear's underwear are made of fabric (these tighty whities don't hold up so well in library books though, and it now looks like he's wearing some very old, rather dirty underwear on the cover of the copy I read).

So one day Bear and all of his naked, square-shaped animal friends—Cougar, Porcupine, Moose, etc—are playing hide-and-seek. Bear hid so well that no one could find him and, eventually, he got hungry, so he decided to run home to eat. On the way, he tripped over a backpack that was left lying in the middle of the path.

He wore it home, where his friends cajoled him into opening. Reluctantly, he did, and it exploded with underwear of all kinds! They then cajoled him into trying them on, which Bear does, and, for the next few pages, he's like the Goldilocks of underwear: Too big, too tight, too dirty (yes, there's a stained pair with stink lines and flies emanating from it.

Finally, he finds the Excalibur of the underwear collection, the tighty whities seen on the cover. His friends then all find a pair of their own underwear from the bag (Thankfully, no one puts on the dirty pair, not even Skunk, whom likely wouldn't mind the smell as much as some of the others).

And, um, that's the story of how Bear and the creatures of the forest came to wear underwear.

Adults may have questions. Why was there a backpack full of underwear of all sorts, including a very dirty pair? Whose backpack was it, and how did they lose it in the forest? Most pressing in my adult mind was why on Earth Bear and his pals would immediately start putting on strange underwear belong to unknown persons, and what kind of message this sends our children.

I feel like there should maybe be a disclaimer at the ends saying that "If you find a strange backpack full of underwear in the woods, do not put them on."

As for the moral of the story, I think that it is this: There is a style of underwear perfect for everyone, and sometimes you need to try new things in order to find them. Also, nudity is bad and shameful and everyone, even the animals of the forest, should cover their shame.

That, or maybe it's just a fun story about underwear, an eternal source of amusement for children (and many adults).

Dinosaur Vs. Santa (Hyperion; 2012): Bob Shea is a favorite illustrator of mine, and it seems like a book of his gets included in just about every column on picture books I put together. This one, released last fall in time for the holiday, but not written about by me until March because I apparently only do these columns every six months or so, is the latest in his series of Dinosaur Vs. books.

I liked the first one a whole lot: Dinosaur Vs. Bedtime featured the title character, a kidney-bean shaped dinosaur that roared his way through various challenges, coming up against a intractable, insurmountable force that no child can defeat, no matter how hard they may want to—the need to pass out at the end of the day (Particularly a day that involves a lot of roaring and conflict-overcoming, like Dinosaur's day).

It's sequels, Dinosaur Vs. Potty and Dinosaur Vs. The Library weren't quite as successful for me, as they didn't have the same strong conceptual underpinning. The Library and The Potty are certainly enemies (of a sort) that can challenge and best a child/dinosaur that can usually "win" most of his/her/its challenges, but the nature of their enmity is quite different from that of bedtime.

I enjoyed the artwork in both of those immensely, but they didn't wow me the way Bedtime did, and felt more like checking in with an old friend than a revelation unto themselves (This is common in kids books turned series of kids books, of course; Mo Willems' Don't Let The Pigeon Drive The Bus is a far different, far sharper and more focused book than, say, his The Pigeon Finds a Hot Dog or The Pigeon Wants a Puppy).

Dinosaur Vs. Santa (which has to be one of my all-time favorite titles of anything ever), is a Christmas book, obviously. In it, we see our familiar dinosaur hero, wearing a variety of cool holiday sweaters, battling a series of Christmastime rituals, each of which he wins with his normal display of roaring and some unusual sound effects. You know, Dinosaur versus a letter to Santa! (ROAR! DRAW! SCRIBBLE! ROAR!), Dinosaur versus presents for Mom and Dad! (ROAR! SNIP! ROAR! ROAR! GLUE! ROAR! GLITTER!) And so on.

There are a few deviations, including Dinosaur versus being extra good, in which he's faced with a plate of tempting cookies left for Santa and must resist eating one of them (he does it!) and then the ultimate test, Dinosaur versus falling asleep on Christmas Eve!

Does he do it? Well, if you've read vs. Bedtime, you know no dinosaur can withstand the force of sleep for too long, but it's a charming conflict nonetheless, with the title antagonist appearing only in shadow.

Shea's artwork is as perfect as always. His dinosaur still looks slightly rough and crayon-drawn, but "real" objects are inserted in the artwork at a more frequent rate, so the cookies and decorations and craft supplies and so forth that Dinosaur interacts with seem to be photographs cut-and-pasted into the art work, giving it a charming collage effect. (The plate of cookies looked especially good; props to Dinosaur for being able to resist that gingerbread man, as I don't think I would have been able to).

Dinosaur has a much fuller range of expressions in this book than in some of the past ones, I think, and it always strikes me as kind of funny and slightly weird when he is making any face other than his roaring face.

And, on the last page, we get a glimpse of his apparently human parents, which reinforces the perhaps obvious (to adults) fact that Dinosaur is just a metaphorical dinosaur:

The Dinosaurs of Waterhouse Hawkins (Scholastic Press; 2001): One of the many, many fascinating things about dinosaurs is how our views of them have changed over the decades since we first discovered them (although arguments can and have been made that humanity has been living with their fossils for centuries, and interpreting them in various ways all along, so that certain mythological monsters are, in a way, early human accounts for dinosaurs).

It can be quite amazing how quickly our understanding of what dinosaurs may or must have been liked has changed, too. I know just in my relatively short lifetime, the dinosaurs I've seen in the latest documentaries I've watched are very different from the dinosaurs I saw in the mid-1990s Jurassic Park film (which, unlike most dinosaur movies of the 20th century, had scientific advisers rather heavily involved), and those were very different from the dinosaurs in the books I read as a child.

In those books, dinosaurs were still slow-moving, cold-blooded giant reptiles, dragging their tails on the ground behind them. T-Rex stood up stock straight, and sauropods spent all their time in swamp water. As outdated as those books might now be, they also included sections on the dinosaurs of Waterhouse Hawkins, the Englishman who gave the world its first view of dinosaurs in the Victorian Era, creating the huge, life-sized models of dinosaurs that graced the Crystal Palace at Sydenham Park in 1854.

You've likely seen these dinosaurs, even if you don't know the whole story of their genesis and the man who designed and built them. That quickly evolving scientific understanding has dismissed his version of the dinosaurs, or course. The most famous example was probably his Iguanodon, which, like all of his dinosaurs, resembled a giant lizard more so than the creatures we now envision. It was quadrapedal rather than bipedal, and bore a rhinoceros-like horn on his snout, whereas now we think that "horn" was actually one of two thumb claws.

This book isn't about what's changed since Hawkins' time (although there is a page at the very end contrasting Hawkins' dinosaurs with 2001's dinosaurs), but is instead a biography of the man, told in three sections or acts, as they're labeled.

Writer Barbara Kerley and artist Brian Selznick (whose name you're likely familiar with from some of his later work) begin their story in England, with Hawkins' boyhood interest in drawing and sculpting, before moving to the 1850s, when Hawkins goes about his project of building dinosaurs with the help of scientist Richard Owen, based on the existing fossils.

They discuss the process of building the dinosaurs, as well as Hawkins' method of trying to sell the scientific community and England in general on his dinosaurs.

In Act II, he heads to America, where he's been invited to build a similar dinosaur park filled with American dinosaurs, to be erected in Central Park. Boss Tweed was against it as a waste of money, and when Hawkins spoke out against him in 1871, vandals broke into his shop, smashed his dinosaurs and buried the pieces somewhere in the park.

In Act III, he heads home to England, where he spends the rest of his life, and Kerley and Selznick suggest the evolution of thinking on dinosaurs and close with a rather elegant image of a little boy in central park, sketching nature just as Hawkins did as a boy, the head of one of the smashed and ruined dinosaur sculptures peering up at him from its secret burial place.

They close with several pages of notes, offering yet more insight into a fascinating man, his fascinating life and historical anecdotes that really should be more widely known. I minored in history in college, and have always been fascinated with dinosaurs, yet I never knew about the planned and abandoned dinosaur museum in Central Park, I'm embarrassed to say.

As picture books go, it's rather wordy, and obviously meant for older readers than...let's see...everything else mentioned in this post. It strikes a very good balance between for kids and for grown-ups though, I think, and deserves an all-ages designation.

Selznick's artwork is great, evoking the look of Victorian England and 19th century America in architecture, fashion and, more subtly, presentation of the material. His versions of Hawkins' dinosaurs are perfect, and there are several very effective images, including the aforementioned closing page, the look away scene of the mysterious destruction of the American dinosaur sculptures (a two page spread shows the workshop from the outside, so all we see is a dark wall, with a tiny illuminated window, in which one can see a fist gripping a hammer and a few chunks of dinosaur shrapnel) and, quite evocatively, scenes of Hawkins walking lost in thought, while little ghostly images of his dinosaurs float in a loose cloud about him.

It's the best kind of historical story—relevant, relatively unknown, powerfully suggestive—told extremely well to a potentially quite large audience.

Elemenopeo (Houghton Mifflin; 1998): The fact that the cat on the cover looks just like a cat that lived with a friend of mine first caught my attention, and the cat's name convinced me to take it home with me.

"My name is Elemenopeo," the book begins, author Harriet Ziefert's words masquerading as Elemenopeo's appearing beneath a painted image of the cat by Illustrator Donald Saaf. "If you don't know how to say my name, just read these letters: L...M...N...O...P...O."

"I may look like an ordinary cat. But I'm not," Elemenopeo goes on. "I always get up early and eat breakfast. Today I'm having a bagel with lox and cream cheese."

While the first image was of the cat looking out the window, resembling a perfectly normal cat save for the broad smile, the second one shows the cat on its hind legs, grasping the bagel which, given the small size of a cat, looks like a pretty big breakfast (Imagine yourself eating a whole pizza for breakfast).

Despite the protestations, Elemenopeo's life seems like that of a pretty ordinary cat, and in first-

One day, the pet door is closed, a small sign reading "Close For Repairs" on it, and thus Elemenopeo's beloved, comfortable routine is interrupted. Paints are discovered, and so, for the day at least, Elemenopeo becomes an artist.

It's a nice, simple, gentle story, perfectly realistic save with only two variations—breakfast and painting. Saaf's painted artwork is perfectly suited to a story about a cat who becomes a painter as well—Elemenopeo's style is much rougher and more primitive than Saaf's more polished and assured style, which is just realistic enough to strike the same realism-with-a-touch of fantasy tone of Ziefert's script.

Paul Bunyan and Babe The Blue The Blue Ox: The Great Pancake Adventure (Abrams Books; 2012): Writer/artist Matt Luckhurst reinvents and reinterprets some of Paul Bunyan's best-known adventures, tying them together into a single, cohesive narrative that emphasizes he and pal Babe's love for pancakes as a driving force in them, and coming up with a few important morals not normally associated with the characters, cheekily delivered (These are the importance of a balanced diet that includes fruits and vegetables, as an all-pancake diet doesn't provide the nutrients that giants or giant oxen need, and to always listen to your mother, who is always right).

One thing Luckhurst does is elevate Babe from pet or sidekick status to that of an actual co-star. As you can see on the cover, he stands on his hind legs, shoulder-to-shoulder with Bunyan. When he's introduced, he's given a full-page introduction with a banner bearing his name, just as Paul is. The narrator tells us that people remember Bunyan and his best friend Babe The Blue Ox as the greatest lumberjacks to ever work in the forests.

No longer a solo star, Paul Bunyan is now part of a comedy duo, with Babe Hobbes to his Calvin, Chewbacca to his Han Solo, rather than, say, Silver to his Lone Ranger, or Battlecat to his He-Man.

Luckner chronicles the over-sized characters' difficulty in early life and their journey out into the world in search of pancakes and adventure. They get both when a man calls them to the scene of an accident. It seems a truck full of flour crashed and dumped its load of flour into the river, and the sun baked the resulting batter into pancakes that had completely blocked the river, preventing logs from traveling down it.

The pair put on their eating hats (this version of Paul Bunyan and Babe have eating hats) and clear the way. They get jobs as lumberjacks, chew on the Rocky Mountains, carve the Grand Canyon and so on.

Luckner's art has the feel of both folk art and roadside art, and has a charming illustrative quality that makes it more perfect still for his story.

His Paul is a big, bearded lumberjack, but he's proportioned as a more or less regular dude—just a really big regular dude (There's a neat image of him as a young boy in school, where he fills the schoolhouse and uses a tree as a pencil; he's so young, he doesn't have a beard yet, just a big, luxurious mustache).

Babe is actually a blue and white ox, with a white spot on the rump and underbelly, and a mostly white head (save for a blue patch around his eye). Babe's ox-ishness comes and goes as the story requires; more often than not, he is anthropomorphic, walking on his hind legs and using his front hooves like hands, although there is a scene where he pulls a plow and he's exempt from school.

The President and Mom's Apple Pie (Dutton; 2002): Michael Garland's picture book about President Howard Taft, seventh of Ohio's eight presidents and first fattest of every president ever, is essentially one big fat joke. Which is fine: Taft was 300 pounds, after all, and that paired with his fantastic mustache make him one of the most cartoon-ready of our presidents, one who really should be drawn more often by more artists.

The story here is that Taft is coming to a small town to dedicate a flagpole, but as soon as he gets off the train, he is distracted by a wonderful aroma, and follows it to an Italian restaurant, where he eats a plate of spaghetti. Next, he smells barbecue. And then Chinese. And, ultimately, the titular foodstuff. Taft follows his nose from one meal to the next, Garland's version of him an enormous but perfectly round circle in a nice suit, nimbly prancing from one place to another on tiny legs ending in tinier feet.

His shape for Taft is delightful, as is the image of the big president running away from his official duties, trailing an entire town trying to keep up with the important but easily distracted head of state. I was enthusiastic about Garland's textures, as everyone and everything looks vaguely toy-like.

This Moose Belongs To Me (Philomel; 2012): Oliver Jeffers' latest book concerns a young boy named Wilfred, who the first page assures us owned a moose. Wilfred himself is fairly certain that he owns a moose, and he's named him Marcel and devised all sorts of rules for Marcel to follow, although Marcel isn't especially inclined to do so.

The story follows Wilfred and he follows Marcel until his insistence on owning the moose, and/or the moose's inability to realize that, causes a sort of crisis, which is later and safely resolved, and a mutually beneficial arrangement is arrived at.

Jeffers' artwork is usually the main draw for me with his books, although the story in this one is among his strongest. The way he draws legs still drives me crazy though (They look fine upon the moose, as moose legs look so different from people legs, and moose don't wear pants or shoes; but Jeffers' people and, on one occasion, a bipedal bear, simply have straight, stick figure-like lines for legs, regardless of how full, fleshed-out and three-dimensional the rest of their bodies are rendered).

Here, the characters—Wilfred, Marcel, a few other people with ideas about the moose—are painted in Jeffers' usual style, while the backgrounds are either plain white voids or landscape paintings Jeffers produced in a completely different style, and/or sampled, visual hip hop style, from other works by other artists.

It's a great-looking book, and maybe my favorite of Jeffers' so far.

Stuck (Philomel; 2011): Speaking of Oliver Jeffers...

Young boy Floyd gets his kite stuck in a tree, and tries to dislodge it by throwing first one shoe, than the other, at it. These both become stuck as well. So Floyd goes to get a ladder and, in an unexpected twist that drives the gag narrative of the book, Floyd throws the ladder into the tree as well.

The rest of the book mostly entails Floyd throwing larger and larger objects into the tree, and, when practical solutions seem to present themselves to him, he instead throws them into the tree as well.

It's a single gag with a few extra-clever variations, but it's an effective one, and I Jeffers is quite good at drawing people and objects being thrown through the air.

The Snow Ghosts (Houghton Mifflin; 2003): This is a small and short book; a little square book that's inches high and inches wide. On the left page of each two-page spread, there's a short sentence or two, and on the right there is an image, a very small image that occupies maybe about 1/3 of the available page space, with a broad white border around each image.

It's about The Snow Ghosts, a group of happy little ghosts that live "in the far, far north, where snow is always falling." It talks about how they spend their days, their hobbies and favorite activities.

Landry's super-simple art is super-charming. His snow ghosts look a bit like little, well-trimmed snow-covered bushes with smiley faces consisting of two dot eyes and a thin, little curve of a smile. They usually lack limbs, unless they need 'em, and while they're usually shaped like elongated gum drops, they can stretch or grow or shrink as their chosen activity—sledding on their bellies, racing on ice floes—demands.

There's not much to the book, really, but what's there is cute, gentle and quite appealing.

The Surprise (Front Street; 2004): I can't say anything at all about Sylvia van Ommen's wordless book without spoiling the plot. Suffice it to say that it is beautifully painted, and tells a cute, simple story about giving of oneself.

3 comments:

I thought that Babe was always supposed to be equal with Paul B,`cause I watched a The Simpsons episode, featuring the two as equals.

I love these reviews and use them to reserve books from the library for my kid. You should check out a cute, newish book called Monkey Ono for your next round of these.

I just found my copy of the Waterhouse Hawkins book this past week while organizing my library; that's an excellent book and I'm glad you spotlighted it.

Post a Comment