I would tell you that most comic books based on videogames are complete trash, but it would be more conjecture than informed opinion, as I don’t read very many comics that are based on video games, due to the fact that they look like complete trash.

Sure I was kinda curious about the old Daredevil team of Brian Michael Bendis and Alex Maleev doing Halo comics for Marvel, or Walt Simonson writing World of Warcraft for DC/WildStorm because they seem like weird endeavors for such name talents, but having no knowledge or interest of those games I never checked them out. I tried a Castlevania comic a while back and it was awful; I saw a new trade based on the property in shops last week, but didn’t even flip through it. I could never even get past the covers of the old Tomb Raider comics.

The only based-on-a-game comics I’ve actually stuck with for a while were the Darkstalkers comics (first from Viz and later from Devil’s Due), which were pretty terrible*, but I had some affection for the game and the character designs, and the Tokyopop Kingdom Hearts manga, because I thought the game looked really cool, and figured reading a comic based on it would be the next best thing to playing it. It wasn’t that great either, but it was still kinda fun to see all the Disney characters interact in an adventure story.

As to why comics based on videogames tend to not be very good (and/or look like they aren’t very good), I don’t know if it has something to do with the essential differences between the interactivity of the original medium vs. the passivity of comics (similarly, movies based on videogames tend to be terrible**), or if it’s because publishers who gain licenses of popular games tend to assume the license alone will sell the book so why bother making it good, or if maybe it’s mostly in my head and comes from my own antipathy towards videogames, having never made the jump from sidescrolling games to the 3-D looking immersive games with all the buttons on the pads (I think the Super Nintendo was as far as I followed videogames on their evolution…?).

If we were to ignore all comics other than those based on videogames, however, to pretend that when we said “comics” we just meant “comics based on videogames,” then First Second’s Prince of Persia is Watchmen. Combined with Maus.

Prince of Persia is yet another videogame that I knew next to nothing about, beyond the fact that it must have been pretty popular since it had at least one sequel and was going to have a movie based on it. That, and that it sufficiently distracted one of my old roommates that he played it for what seemed like four or five days straight.

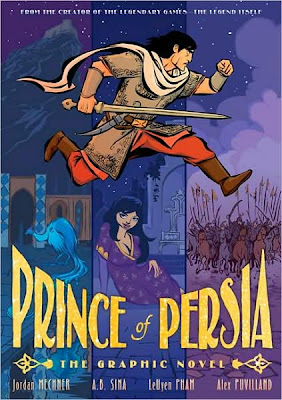

The cover of the First Second graphic novel sure seemed to set it apart from most video game comics; there’s the titular prince, running like the star of an old-fashioned sidescroller, above a triptych of images: A strange-looking bird, an exotic princess in a come hither pose, and an army of guys on horses waving scimitars.

The title is in shiny gold, upraised letters, sprinkled with little star-shaped holograms. It’s kinda cheesy, but a neat kind of cheesy; tilt it under the light, and the logo gets all magical on you. I was amused to see beneath the words “Prince of Persia” the words “The Graphic Novel,” I guess so that readers won’t become confused and think they were playing a handheld videogame with archaic graphics while reading…?

In smaller font, across the top are the somewhat portentous words “From the creator of the legendary games—the legend itself.”

But it’s the imagery and format that is most striking: This isn’t your traditional American licensed comic book, released as a four-to-six-issue story arc to be collected and re-sold in a trade later—it’s an original graphic novel. The art isn’t poor man’s superhero art, but an honest-to-goodness art comics cartooning style. A glance at the cover is all you need to know that First Second is taking this book seriously.

The credits are a little on the murky side, at least at the top. Original game creator and designer Jordan Mechner gets a “created by” credit, although he doesn’t seem to have done any of the writing of this particular story (Based on his extensive afterword, I got the sense that he played a sort of producer-like role with the graphic novel, but I’m not sure).

It’s written by Iranian born A.B. Sina, and drawn by the art team of LeUyen Pham and Alex Puvilland (the former a children’s book illustrator, the latter having worked for Dreamworks animation), and their work is beautifully colored by Hilary Sycamore.

The story they tell is a surprisingly, refreshingly complex one, with none of the markings of an origin in a game of any kind—while there’s plenty of action (When a lion lunges at one of the titular princes, dude cuts him in half from face to tail with a sword!), it’s all dramatic in nature; there’s no running and jumping about for the sake of running and jumping, no levels to clear or bosses to fight. Scott Pilgrim operates on arcade logic to a far greater extent than this book with actual arcade origins***.

Sina seems to circumvent the source material, or at least the most recent reflections of that source material, instead reaching back to the types of stories that originally inspired Mechner in creating the franchise: Legends from his own culture, 1,001 Arabian Nights fairy tales, Hollywood orientalism exotica. And it’s this inspiration that he weaves into a story that is very much about story, and the way stories from one generation can powerfully affect others.

Prince of Persia is set during two different centuries, the ninth and the thirteenth. In the ninth century three great friends Layth, Guiv and Guilan were inseparable, and were all considered the prince of their city Marv. As they grew older, Layth married Guilan, and he became the ruler of Marv, while Guiv, Guilan’s brother and the true heir to the throne, was cast out of the city—in part for perceived betrayal, and in part to avoid bloodshed from an outside army that wanted Layth on the throne. Guiv lived among the ruins with a monstrous magical talking bird and strange visions and later an army of lions (And did I mention he totally cut a lion in half? Or that he swordfights an army of skeletons that look all Harryhausen-y? Because he does.)

In the thirteenth century, a teenage girl named Shirin cuts her hair, escapes from her corrupt government official father’s palace, and poses as a boy until she falls down a well and meets Ferdos, a mysterious boy who lives in the same ruins Guiv once dead (and looks an awful lot like a Bruce Timm drawing of Paul Pope).

Ferdos makes drawings that tell the stories of the ninth century trio, and he and Shirin see the actualization of a prophecy made in Layth and company’s time. That prophecy informs the actions in their century, and Sina and company weave in and out of the two narratives throughout the entire book, so that the two stories climax at the same time. It’s an amazingly well constructed story, one that manages to withhold bits of important information until the precise moment where their revelation will have the greatest impact.

I can’t say enough good things about the artwork. It’s a highly illustrative, very comic-book-y looking graphic novel—the images are flat, obviously hand-made and hand-drawn, something I take greater and greater pleasure in these days when so many comics seek pseudo-photorealism through excessive photo reference and reliance on highly-gradiated computer coloring.

Sycamore’s coloring is smartly done, giving the panels the look of immaculate old-school 2D animation. There are delicate tones and observant decisions on what to color what when and why, but these are all in service to the lines of ink laid down, and do nothing to obscure or overpower them.

There are some showy techniques, like the soft lines of the magical bird that separates him from the world he walks through, and Pham and Puvilland’s switch to era-appropirate style when depicting events seen in Ferdos’ scrolls, or the juxtapositon of the two epilogues in vertical stacks of panels separated by flowing water, but it’s the panel-to-panel story telling and fine character acting that make the art so damn impressive more than any of these other more idiosyncratic strategies.

I implied that this was probably the best based-on-a-videogame comic I’d ever read, but that’s probably pretty feint praise, huh? So forget videogame comics then; this may not be the greatest comic comic period, but it is a pretty great one.

Or, to put it as simply as possible, Prince of Persia rules.

Mecher provides an eleven-page afterword focusing on the life of the “Prince” character, who was older and starred in far more games than I realized: Mechner conceived him in 1985 and he was in a game by 1989, and then a whole series of games, for the Nintendo, the Sega Genesis and the current generation of platforms I don’t understand. It’s a pretty fascinating piece of text, not just because it educated me on something that I was ignorant of or because it framed this graphic novel as a distillation of a story that had wound through centuries old fairy tales into Hollywood movies into Mecher’s childhood ambitions of being a comic creator into his career into videogames before reaching this point, but because it frames the story you just got done reading in a new and interesting way.

Mecher reminds us that there is no real prince of Persia, the characters in the games and the comic, in the old movies and old stories are all just iterations of some one, true prince lost to time; splintered aspects of some sort of Ur-Prince, shadows on a cave wall caused by the unseen prince walking before a fire.

In the graphic novel, there’s no definitive prince, but about five princes who are all the prince of Persia, and it’s there that I think this graphic novel bears the most in common with video games. They allow players—millions of them, over the course of almost a whole generation now, in the case of Prince of Persia—to at least temporarily become the protagonist, in a more immersive way then even the best fiction can.

You can read a comic or story or watch a movie about a prince and get swept up in the adventure, but it’s hard if not impossible to ever completely break the walls between character and reader and step inside them and become that character. But in a videogame, it’s as easy as pushing a button.

This graphic novel lets us follow the prince(s) without ever becoming them, of course, but it acknowledges that it’s a role open to many, rather than just one.

Just out of curiosity: Do any of you have any good based-on-a-videogame comics to recommend? If so, please do so in the comments section. I think I mentioned every one I’ve ever read, and I know there are plenty more that I never have, and probably aren’t even aware of.

RELATED: Hey, good timing! Michael C. Lorah interviewed most of the creative team for Newsarama.com, and asked Mechner about some of the things I wondered about while reading. You can check out the interview here.

*Although the Devil’s Due comics did feature some pretty cool gag back-up stories.

**You know what was completely genius though? Putting Dennis Hopper in bright blonde cornrows and a business suit to play the King Bowser character in 1993’s Super Mario Bros, where he held his his hands held like a T-Rex and kept referring to the heroes as mammals because he was a super-evolved dinosaur. That was awesome. The movie sucked, but I somewhat shamefully admit to having watched repeatedly due to my crush on Samantha Mathis.

***Okay, it was a home platform game not an arcade game, shut up I’m a Luddite I don’t care you know-it-all jerks!